I created a Twitter poll:

https://twitter.com/KAErdmann/status/1795861572587229221

The answer is C: Homes higher, land lower. It received 14.9% of the vote and the opposite answer received 43.4% of the vote.

Homes higher, land lower

Peter Tulip had it right:

The answer is C. Marginal cost of structures increases with quantity. So homes (=structure?) would rise in price a bit. The demand for housing is inelastic, so increased supply reduces the value of the housing stock. So, given flat home prices, the value of land would fall a lot

Actually, I think the answer can even be a bit simpler than that. The total value of all structures is Price x Quantity. Peter is arguing from standard supply and demand logic that P will increase, but I was thinking in more elementary terms. If zoning allows more homes to be constructed, Quantity will increase.

I think @McgrevyRyan got to the point well, too:

Total value of land falls, but there is a lot of spatial heterogeneity. Land prices increase in high-demand locations - and decrease in low-demand locations.

@GeorgistSteve, @ScootFoundation, @andersem, @Loganb, @BarryUrbanism, and @creid815 all seemed to strike a similar conclusion.

Even though the correct answer received the least votes, it received the most comments. I suppose this is good news. It’s like those University of Chicago polls of economists. The correct answer wasn’t the most popular, but it was the most popular among those with high confidence.

This is hopeful, because I complain a lot about economists giving too much weight to agglomeration effects - the value created by the development of large cities - and not enough weight to scarcity - the excess profit pocketed by owners where others are prevented from building competing units. The answers to the poll suggest that agglomeration is being generally overestimated, but that those who feel strongly enough about the topic to comment give more weight to scarcity.

This isn’t a conceptual question. It’s an empirical one. There are worlds in which agglomeration would dominate and there are worlds in which scarcity would dominate. Agglomeration and disagglomeration economies - the positive and negative externalities created by urbanization - dominated when metro area scarcity wasn’t binding. And they still dominate in some ways cross-sectionally within a metro area, even when the metro area itself suffers from scarcity.

It would be hard to come to a conclusion here purely from textbook thinking.

I think one thing that creates confusion is trying to imagine the effect of upzoning on a unit by unit basis. The scale of this question is too large to imagine in that way, and so the conclusion from that sort of mental process basically reflects the types and scale of units you didn’t think to imagine.

It’s sort of an ironic example of Bastiat’s seen and unseen. The traditional way that the “unseen” leads to biased thinking is that laypeople don’t appreciate the 2nd and 3rd order effects that careful economic reasoning leads you to. But, on this topic, I think what happens is that PhD economists focus on 2nd and 3rd order effects of refined economic theory at the expense of more basic facts that have a more important scale in our idiosyncratic time and place.

For example, a common NIMBY refrain is to see a few high-status condo buildings in Manhattan that are mostly empty vacation apartments for the rich, and conclude that the reason New York housing is expensive is that we are building too many pieds-a-terre. That is the seen. The unseen is miles and miles of unchanged neighborhoods bumping up against arbitrary density caps from Queens to Massapequa to Hackensack.

In contrast, sophisticated economists see a few high-rent condo buildings in Manhattan full of urban professionals, and conclude that the reason New York housing is expensive is that it is a really productive city that draws in the world’s most productive workers. That is the seen. The unseen is… well, miles and miles of unchanged neighborhoods bumping up against arbitrary density caps from Queens to Massapequa to Hackensack.

Related to this, as subscribers of the Erdmann Housing Tracker know, scarcity has a tricky effect. It’s effect happens on a metro area scale, but in an asymmetrical way. You could say that LA has a large scarcity factor and Austin has a small scarcity factor, and you could build a pretty accurate model of home prices in each city by applying a single constant to each. But, the constant would interact with incomes. Scarcity has a much larger proportional effect on prices of homes in LA with poor tenants than it does on prices of homes in LA with rich tenants.

All of this makes it very tricky to think through “changes to American housing” either with a model or a bottom up accounting.

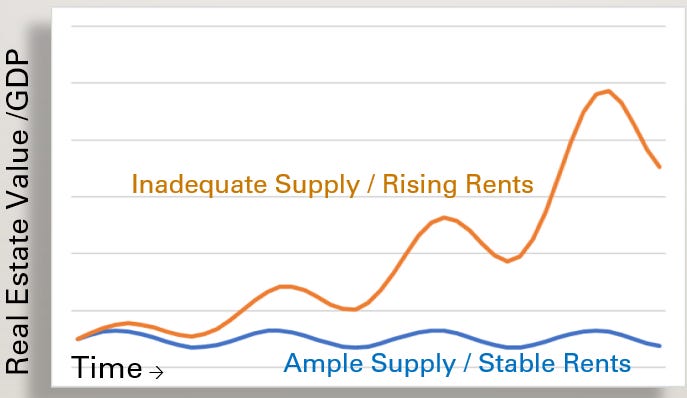

You can start with Peter Tulip’s point, that, in the aggregate, housing demand is inelastic. When supply is limited, we spend more on it. We lower how much we use, but the price goes up more than the quantity goes down. You can see this in very broad terms in the US since the 1970s. Housing (in terms of total rental value) has taken an increasing portion of total expenditures since zoning, et. al. has started to bind on urban housing supply. That is a combination of fewer homes and higher rents on the homes we have. The increase in rents outpaces the decline in units. It adds up to more spending (Figure 1).

Residential investment lines up with this. Residential investment is the application of capital to new structures. The decline in real housing relative to real growth of other spending has been parallel to the decline in net residential investment (Figure 2).

As residential has declined, price volatility has increased (Figure 3). Before the 1980s, the total market value of residential real estate increased in parallel with the increase in new structures. Real estate value was mostly a reflection of structures. Since then, investment in structures has declined, and total value swings wildly. Where value changes in a way that is unrelated to investment in structures, that is a change in the value of urban land. Or, through the lens of Figure 1, the change in real housing expenditures (rental value) is the change in structure value. The inflationary change in housing expenditures (inflated rental value) is the change in land value.

Clearly, over the course of the last half century, declining rates of construction of new homes has been associated with rising land value and declining value of structures, relative to other spending and incomes.

There are 2 possibilities here.

The land value represents scarcity. This is exactly what the data would look like if obstructions to urban housing supply had led to rising rents because of scarcity.

The land represents agglomeration value in major urban centers, and we just happen to have tripped into a cosmic coincidence that at the same time our cities have become a new amplified source of productivity, we also stopped investing as much into housing. And, moreover, the cities that are the sources of the most amplified urban productivity are, coincidentally, the cities that block new residential housing the most (Figure 4).

Notice, in Figure 3 that there are 2 orthogonal stories here. The long-term decline in residential investment is associated with rising real estate prices, but cyclically, rising residential investment is associated with rising real estate prices. I suppose this suggests an added wrinkle to my meme chart.

There are actually two ways to misattribute rising costs to something other than supply scarcity. The first, which I usually point to, is to always notice the rising costs during a cyclical expansion. So, a persistent rise in housing costs will look, in real time, like a series of increasingly extreme cyclical events.

But, there is a second possibility. You could notice the persistent rise in costs, but misattribute them to urban productivity and agglomeration economies.

On the topic of whether new construction would lead to higher total real estate valuations, I will make a few points here.

Lower home values and higher land values

As the question was posed, it should be definitionally true that more residential investment would lead to an increase in the total value of structures. As I mean the question, the value of structures is the actual real cost of new walls, roofs, foundations, and interiors, or the replacement value of existing structures. In most normal models of supply and demand, more quantity will lead to higher total value.

I’m definitionally saying that the change in the market value of existing homes is a change in land value.

So, the most popular answer, that broad upzoning would lead to lower value of structures and higher land values either has the empirics wrong (imho), or didn’t use my definition of structural and land value, or assumed it was a per-unit question rather than an aggregate market question. I suspect the most popular reason for voting that was was to think about it on a per-unit basis, and to conclude that more building would lower the price of individual housing units on upzoned land but raise the value of the underlying land.

As I mentioned above, I think this is making the mistake of only considering the change in value on land that is both upzoned and significantly developed. On this, let me make one point about scale.

I am an outlier on the shortage front. I think we are short something like 20 million units. Maybe more. I think we need at least 20 million more homes to reverse the scarcity premium in American housing. That’s less than a 15% increase in the total American housing stock.

In other words, if 1% of lots were changed from a single unit to a 15 unit building, then 99% of lots would be unchanged with no source of demand left to inflate their value.

If 5% of lots were changed from single units to triplexes, then 95% of lots would be unchanged with no source of demand left to inflate their value.

My point here is that the scale of the seen to the unseen is very different. There is no plausible rise in the land value of the upzoned lots that turn into triplexes or 15-unit buildings that could remotely amount to more added value than the reversal of value that the unimproved lots would experience in a market fully satisfied with supply.

Passive vs. Active Agglomeration

Let’s say that it really is a coincidence that the cities with the least building happened to be the cities that found their magic productivity sauce over the last few decades. It just happens that cities that didn’t grow were cities that became valuable.

Even in that case, the point remains that their added value didn’t come from building homes. It came from a change in context.

The most expensive cities were among the slowest growing cities. So, they didn’t become more productive by attracting more residents. City size didn’t change much.

And the fastest growing cities haven’t gotten more expensive. So, there hasn’t been some change in the generalized value of cities. Getting bigger hasn’t become more valuable.

It is plausible that San Francisco, Boston, New York City, or Los Angeles became more valuable as they were. But it would be unempirical to say that San Francisco or New York City became more valuable by growing.

The demand for productive workers in some sectors to live there increased. But, even if this is the case, the increase in their productivity wasn’t related to housing production. There is no reason to infer that building more homes will make them more valuable. Building more homes wasn’t the source of their value to begin with.

Certainly, the fact that there was some number of homes there already was an important facet of their productivity. San Francisco wouldn’t be an economic powerhouse if it was all sheep meadows.

But, asserting that San Francisco has agglomeration value is not the same as asserting that marginal changes in total metropolitan area housing matter much to that value. Some subset of workers in the expensive cities are there because those cities hold extra value for them. But, on the margin, the price of housing in the expensive stagnant cities has been set by the maximum rent that former residents were willing to pay before they moved away.

As Figure 6 implies, every high growth city trends toward the normal nominal level of spending on housing. Over the long-term, in macro-terms, eventually growing cities become more dense and costs rise. The leads to tradeoffs such as smaller units, and within a city, it leads to some land value appreciation where density increases.

So, there is some world where growing cities might lead to higher total value of both structures and land. But, I don’t think an economy where that was the important margin would look like Figure 6.

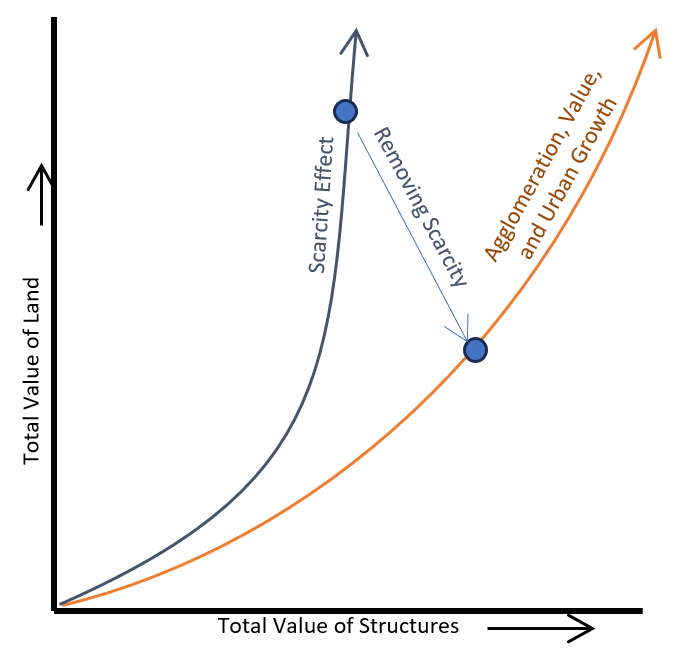

Imagine every major metropolitan area in a beginning condition of zero homebuilding. They would line up vertically on the y-axis according to how much demand there is for living there, how productive they are, and how much agglomeration value they have.

Then, if you change the condition to add housing, they would all move down and to the right, toward where Phoenix is on the chart. As that process reiterates over time, agglomeration effects and the cost of density would change the composition of housing expenditures related to the price/income ratio in the mid-single digits. And some of that change might reflect higher total land value. Larger cities in the future would have total real estate with higher total values - because there would be more structures and because the land would be worth more.

This is why it is an empirical question and not a conceptual one. There are worlds where “both higher” would be the answer. But the most expensive cities in those worlds would not be in the top left quadrant of Figure 6. The scale of the scarcity effect on the top left quadrant far outweighs the scale of rising land value.

Migration flows from LA to Phoenix are significant. On the other hand, for decades migration flows from the Midwest to Phoenix have been significant. The former is due to scarcity in LA, the latter is related to productivity and agglomeration economies in Phoenix. The relative scale of the effects on housing costs seem clear.

The total value of both housing structures and land have increased over time in every city where more Americans are moving in than are moving out. This confirms the conceptual intuition of the “higher and higher” answerers. But, in every city that, on net, families are moving out of, and especially families with low incomes are moving out, the total value of structures has been stagnant while the total value of land has skyrocketed.

Figure 7 compares the real estate values of a city like LA to a city like Austin, and visualizes what happens when LA becomes more like Austin. The “higher and higher” intuition is based on a stable equilibrium. “higher structures and lower land” is a transition from one equilibrium to another.

Upzoning is “removing scarcity”. But, yes, if more housing is constructed for economic reasons, then values move up these curves wherever scarcity has set the curves to be.

Passive Agglomeration or Housing Supply Depression?

Finally, there is the problem that rent inflation has been high across the country for the past decade. And, rising real estate values are mostly a reflection of those rising rents. Rent inflation is a reflection of rising land value.

Our coincidence is now occurring in every major city. Are rising land values across the country the result of scarcity? Or are they from newly discovered agglomeration economies that just so happen to coincide with a depression in housing production?

The decline in housing production across the country means that American families don’t have an outlet valve now to move to cities with elastic housing supply. Rents are rising everywhere. That has been very bad for American families, but it does get rid of the statistical problem that families sort across metropolitan areas by income when there is a regional housing shortage.

Since 2008, production of new housing has declined the most in cities with lower incomes (Figure 8).

And, in cities with lower incomes, where, now, there are fewer new homes, rents have increased tremendously (Figure 9).

The average Price/Income ratio of ZIP codes in the 30 largest metropolitan areas has increased from about 4x in 2002 to about 6x today. That is in spite of sharp tightening of mortgage lending regulations that lowered home prices relative to rents.

The scarcity vs. agglomeration question appears to have a clear answer here, too. Scarcity has been raising housing costs everywhere. Moving LA from the blue line in Figure 7 to the orange line would lower land values and raise the total value of structures. But, instead, the entire country has moved from the orange line toward the blue line.

Other Twitter Comments

Here are some of the other comments. These all suggest answers different than mine. Some of these, in my opinion, are contrary to my points above. Some of them, I think, are more a reflection of different mental accounting - thinking of new homes and existing homes differently, thinking in terms of individual units instead of total value, mentally bundling the land and structures so that changing prices are attributed to the structures, etc.

With the ability to clarify, I’m sure the poll results would have been somewhat different.

I interpreted the question as being about existing structures.

Structures the same & land lower

Brilliant poll about artificial scarcity. The easiest way to find he answer is to think of the opposite - what would happen no new construction would be allowed at all anymore? -> prices for both would go up. But, the devil is in the details. Rising prices are not a good thing.

@yimbychris tweeted:

The land would be higher from increased density but cheaper on a per plot basis.

There's more stuff built there, so the total value of stuff increases. There's more stuff you can build there, so the total value of land increases.

I said homes lower and land higher because I think that is what would happen in the short term. In the long term, more structures would be built and I expect the total value of land and structures would go up.

Most values unchanged. Some land zoned for apartments marginally lower. Land currently zoned for SFH but highly coveted by developers skyrockets in value. Most land zoned for SFHs unchanged or marginally higher.

No change to either

OT but in the ballpark---

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/06/us-economy-excellent/678630/

You have to read this paean to the US economy all the way to the second to last paragraph...oh, that.

Can't buy a house, afford health insurance, college for the kids, and two-parents working need expensive childcare...

But be happy!

I'm glad I didn't participate in this poll--I would have chosen "B" and been wrong. My excuse is that I tend to view all architecture as a continuously depreciating factor in real estate because that's the reality I face as an architect and a homeowner. In fact, I'm so cynical that I see many buildings in urban areas as having negative value with respect to the potential value of the land they're occupying. The underoccupied or abandoned strip malls that litter America are impediments to housing creation, especially when they're located in zoning districts that mandate low-density crap like that.

Most homeowners have an incentive to object to any upzoning changes, even when there is a strong potential upside to their community for redevelopment. Scarcity skews home values upwards in just about any location; even in downtrodden areas.