In parts 1 and 2 I have been working through the shape of housing supply and demand within individual metropolitan areas.

Figure 1 here is the basic picture of supply and demand over, say, a year, in a given city. Until recent decades, local economic conditions moved demand curves left and (mostly) right, and the right end of supply curves was generally far enough to the right to accommodate that. There wasn’t much difference in home prices from city to city. Successful cities grew faster and less successful cities grew slower. The average family in all of them spent 3 or 4 times their incomes for a house.

Over the course of the 20th century, infill multi-family housing construction became increasingly difficult. A handful of cities developed local supply conditions so tight that demand moved farther to the right than the right hand limit of supply each year, and those cities became very expensive. Most cities could still compensate for their lack of infill construction with single-family homes in the exurbs.

Then, after mortgage access was sharply curtailed in 2008, that compensating outlet was cut off. Every city’s supply curve was squeezed to the left. And, now they are all more expensive.

Here, I will walk through the supply and demand in several cities to compare how different combinations of supply and demand conditions lead to different outcomes.

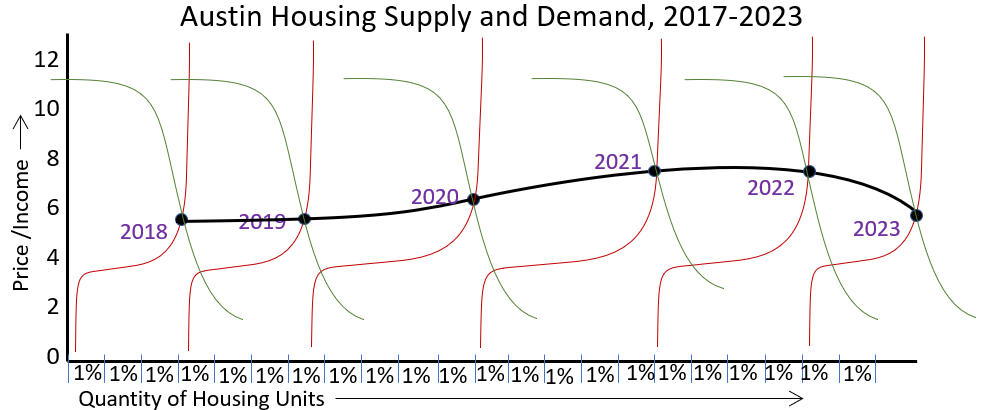

Here, I will accumulate supply over time. Each year, the supply curve will move to the right, as more homes are built each year, and I have estimated the shape of a new demand curve onto each supply curve based on the clues from local conditions.

Austin

Figure 3 shows housing supply and demand in Austin from 2018 to 2023. Generally, Austin runs pretty close to its supply limits, but it meets demand as well as any city has since 2008. In 2021 and 2022, demand briefly outpaced short-term local supply limits, and so the demand curve moved further up into the inelastic supply conditions that are triggered by growth. The results are similar to what had happened in Phoenix in 2006 in Figure 2.

This is generally an unsustainable condition. Conventional wisdom is correct that Phoenix was destined to give back some price correction after 2006. And the same was true for Austin in 2022. And it did! In both cases, as I described in part 2, this really is the classic “bubble” scenario where prices rise temporarily because demand within a given time period is high enough to test supply limits, but long-term supply conditions will correct prices back to normal. Inelastic short-term supply and elastic long-term supply.

The mortgage crackdown, combined with local limits on infill building, has harmed supply everywhere, but Austin has done about as well on both fronts as any city has, so demand has settled back in a bit above the traditional comfort zone. Austin is somewhere between Phoenix in 2002 and Phoenix in 2024 from Figure 2. It is closer to Phoenix 2002 than just about anywhere else.

The key thing to keep in mind here is that after cities like Phoenix corrected back to the elastic part of the supply curve in 2007, the federal government pushed prices down even further through mortgage suppression. That was an entirely unrelated development. But, it has left almost everyone with the impression that when a surge of demand corrects, it will lead to a strong pendulum swing in the other direction. So, many people are looking for home prices in Austin to continue to fall.

That isn’t going to happen. Population growth would have to go negative for that to happen. The web of myths and misunderstandings about 2008 has led to a whole patchwork of hallucinated triggers that caused prices to collapse so deeply. A big one is that builders just kept speculatively completing new homes in overly-optimistic herding behavior, leaving those cities with a glut of homes.

Builders don’t do that. The number of new homes for sale was declining by the summer of 2006. By October 2009, the number of new homes for sale was down to a 38 year low. From October 2009 to February 2012, the Case-Shiller index dropped another 12%. Prices didn’t collapse because there were too many homes for sale.

As I mentioned in part 2, when a surge of demand pushes a high-growth city like Austin into inelastic supply territory, it will tend to create pent up demand from potential newcomers who delayed their migration because of high prices.

There is a lot of chatter of the reversal of some post-pandemic work-from-home movers - people reversing their migration because they are being called back to the office. The debate about the size of that swing is still open. But, there is also pent up demand from price-sensitive movers who delayed their moves to Austin because of high prices.

All told, these broad migration trends do not turn on a dime. In 2008, all migration practically ground to a halt because of the mortgage crackdown. That was a non-repeatable anomaly. Austin isn’t going to shift from 3-4% growth, year after year, to negative growth, over night. And, if it even shifted down to 1-2% growth, builders aren’t just going to keep building until there are tens of thousands of empty homes. Again, that doesn’t happen and it didn’t happen in 2008.

This is basically the categories of housing conditions. Austin has been in the capacity condition and has just moved to the right end of the normal condition. Practically every city for the entire 20th century moved around within the normal condition (the flat part of the supply curve) 95% of the time. It takes an earthquake of a disaster to leave that condition. Austin prices have returned to normal, cyclically, and they will stay there for the foreseeable future.

And builders will keep starting new homes there, probably at about the same rate they have been for years, and selling them, and then starting new ones.

Las Vegas

Before 2008, Las Vegas looked much like Austin does today. Migration from California started to displace migration from other parts of the country, as I described in part 2, which led to rising prices. Building started to slow down in 2006 and 2007, even as prices remained elevated.

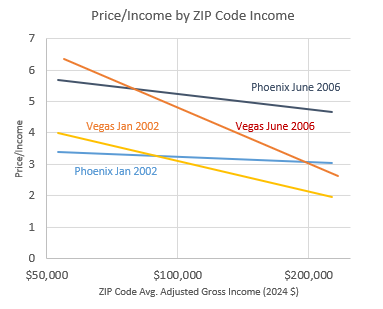

In Figure 4, I compare price/income ratios within Las Vegas and Phoenix. As I described in part 2, demand surges tend to raise prices across a metro area. Inequitable prices that rise more in poorer neighborhoods are generally due to inadequate local supply. With perennially inadequate supply, locals trade down within the metro area in order to lower costs, pushing demand down-market.

The price/income line was already more sloped in Vegas in 2002 than it was in Phoenix. Even though Las Vegas had a high growth rate, the slope of the price/income line suggests that supply had been inadequate to meet demand for some time. It could be that by 2005, low end prices in Las Vegas were being driven higher by speculators, unqualified home buyers, flippers, etc. But if that were the case, it would be odd for new permits to be declining.

There was obviously a rise in speculative behavior and reckless lending, but the most egregious activity happened when market indicators had turned bearish. It’s really strange that the city that is popularly associated the most with a speculative building frenzy had declining construction activity and a price pattern associated with inadequate supply at its most speculative point.

It would be helpful to have a literature on that, but since incuriosity about these issues has been panoptic, there is none.

In Figure 5, you can see the the slowdown in supply and demand going into the Great Recession, and then, growth in demand grinding to a halt in 2008 and 2009. Since then, Las Vegas has been a very different market. Growth is relatively low every year, and demand keeps outpacing supply a little more each year.

Or, maybe it isn’t that different. Maybe Las Vegas was transitioning toward perennially inadequate supply already by 2006.

It’s hard to say definitively what Las Vegas’ alternative path might have been. We can say definitively today that Austin will continue to grow and that Austin’s prices will settle back near the flat part of the supply curve and maybe even move all the way back down to the flat part of the curve.

The demand shock (both the collapse in migration and the collapse in mortgage access) pushed demand in Las Vegas all the way through the normal supply zone and down to a low level that was associated with more price contraction and vacancies. It seems likely that if the 2008 demand shock hadn’t come, Las Vegas home prices would have never fully corrected. Maybe Vegas’ 20th century growth rates would be a thing of the past in either case, and Vegas would have a worsening affordability problem today even if national construction rates had remained higher.

Somebody tell Joe Stiglitz.

Los Angeles

For Los Angeles, in Figure 6, I have removed some years’ demand curves just to keep it from being too cluttered. The annual supply curve is so thin that there is a lot of information bunched up together.

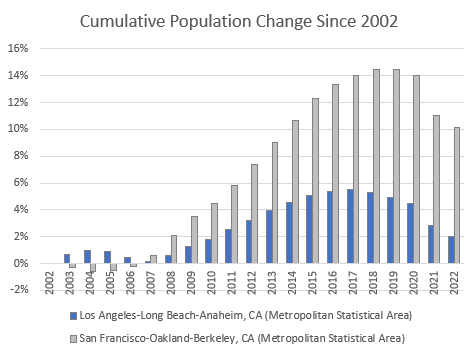

Between 2002 and 2005, the mismatch between supply and demand was high enough that the demand curve got pinned up against the upper bound. At that point, there is no room for new growth in Los Angeles. Every new household must push out an existing household. According to the BEA, the population declined slightly from 2004 to 2007 (Figure 7).

Over those three years, new permits were issued cumulatively equal to about 2% of the existing housing stock, but those were claimed by rising demand in the form of less intensive use of the housing stock (converted units, smaller households, etc.). And otherwise, the housing market was strictly a musical chairs game.

The recession created an extensive contraction in housing demand in Los Angeles, so that by 2012, the demand curve had moved back down to a significantly lower part of the supply curve even though population returned to slow growth.

By 2013, low supply started to bind again. By 2018, population was declining again, and by 2020, the demand curve was pinned back up near the upper bound.

In recent years, new homes equal to about 0.5% of the existing stock of homes have been permitted annually, and population has been declining by roughly 1% annually. That suggests that even if, at a minimum, the LA area tripled its permitting rate, its demand curve would still be pinned at the upper bound.

How much would LA home prices decline with each additional percentage point of supply growth above that? It’s difficult to say because the question is what is the shape of the demand curve extending out to the right? How can we measure demand among those who are not engaged in transactions? So, I’m not sure the question can be quantitatively assessed.

How Much Will New Supply Lower Prices?

In its current condition, new housing, even at multiples of its current low level of production in Los Angeles won’t change the average price/income at all. Between the moderate increase in demand for housing per capita over time as our incomes generally rise, and the large number of households who will choose not to migrate away if rents moderate at all, it appears that Los Angeles could grow its housing stock by more than 2% annually under current conditions with no price effect. The new housing would mostly reduce regional displacement.

I previously made a broad estimate that Los Angeles would only have needed to grow somewhere between about 1.7% and about 3% (somewhere between Tampa and Phoenix) annually to keep home prices moderate. Above that amount would, presumably, cause prices to move down the steep part of the supply curve.

The 3% growth rate assumes that for each household displaced from LA, there was an additional household that chose not to migrate into LA because of high costs. In the paper where I established these patterns, the steep price/income slope was strongly related to outmigration but only weakly related to in-migration. This would suggest that the demand from newcomers is less price-sensitive than the demand from locals. So, the growth needed to move LA’s demand curve down off the upper bound in Figure 6 would be less than 3% annually.

I think the facets of housing that I wrote about in part 2, and went into more depth in an earlier post, provide some illumination here. In an undersupplied market like LA, every household is making tradeoffs. The families that are displaced have finally used up their tradeoffs, which is why the demand curve becomes very elastic on the margin and has an upward bound in Figure 6. But, families that move in can make many other marginal tradeoffs in the size of the home, neighborhood amenities, etc. in order to make a move work. Figure 6 measures “Taking up a unit of housing in LA”. That is a relatively binary expression of demand that is bundled with all sorts of other tradeoffs. Tradeoffs that newcomers can make and that leavers can’t make any more.

But, that only tells us about the newcomers. There could still be many other potential newcomers who would boost demand as supply pushes prices down. It’s hard to know how many price-sensitive potential newcomers remain.

On this point, the NIMBYs (“New housing will just attract more rich newcomers.”), the agglomeration-focused economists (“More density attracts productive workers.”) , and the supply skeptics (“We have so many homeless people because this is such a popular place to be poor.”) are all wrong. The rich, productive workers are generally coming in any case. They have the easiest tradeoffs. It is potential middle-income and low-income newcomers that are more price-sensitive.

So, on this point, I would say that the growth rate required to stop prices from rising is probably not higher than the rate at which a lot of other cities grow (like Tampa and Phoenix), but it could very well be that a normalization of prices would come about slowly. There could be many households who haven’t moved to LA because they are unwilling to make the tradeoffs required.

A moderate growth rate in any given year would have kept prices low, but cumulatively, the deadweight loss from 30 years adds up to millions of homes.

In addition, there are the millions of households that have already been displaced. Would some of those return if prices moderated? This is a potential source of demand that a deeply unaffordable city like LA would have that other cities do not. So, it might be the case that when Austin or Phoenix experience a 10% or 15% cyclical boost, that boost is quickly reversed, but that the reversal wouldn’t be so quick in cities that have already created mass displacement among families that had strong local ties. How quickly do those endowments decay in the years after those families move away? How many would move back in a heartbeat if they could?

Finally, all those tradeoffs. Within the existing households of LA, there is a range of households at the low end that just take rent inflation on until they can’t anymore, because they have made every tradeoff they can, and those at the high end who keep their housing costs manageable by making those tradeoffs. As supply expands, the existing households will reverse those tradeoffs and increase their consumption of housing as costs subside and supply rises.

This is another form of embedded demand hanging out there to the right of the supply curve. As supply increases, the quantity of housing demanded by existing Los Angeles residents will rise.

Again, I don’t know if there is any reliable way to measure these elasticities. But, I think we can intuit that two things can both be true:

The “superstar cities” aren’t that super and that they could have avoided such high costs if they had even just grown at rates common in average sunbelt cities.

If they can manage to grow at rates common in the sunbelt, it could still be a long, slow process to get prices to decline to normal levels.

San Francisco

LA is losing people because of trade-offs. San Francisco is losing people because of a demand shock. Figure 8 shows supply and demand in San Francisco. San Francisco has only built moderately better than Los Angeles. But, in recent years, there has been a significant outmigration motivated by a decline in the city, not by a lack of housing.

Figure 9 shows the price/income pattern across San Francisco that I use in the Erdmann Housing Tracker.

The shift in demand from 2006 to 2011 was like the shift in every city. It was just a product of a slowing economy followed by the exclusion of borrowers with any apparent default risk from the buyers market. More housing supply would create the same end result permanently. Tightening lending standards only created that result temporarily. Eventually landlords and cash buyers purchased those homes, and rents increased on those homes until their prices became much higher again. So, San Francisco eventually returned to its pre-crisis condition.

As shown in Figure 2, today LA is still where San Francisco was in 2022. But, in the two years since then, the whole curve has lowered in San Francisco. San Francisco hasn’t gotten cheaper because more homes have improved affordability for poorer residents. It has gotten cheaper because richer residents have lost a preference for living there.

This will be interesting to watch. This is the deepest cyclical depression I have seen in any city in the 22 years my data tracks them. Usually, cycles are fast-twitch and return to the stable mean.

Usually, that happens when local housing construction slows down to let demand catch up. But San Francisco already doesn’t build many homes. That makes the demand crash even more striking.

Will the cyclical collapse in San Francisco become a supply story? Will demand decline so far that San Francisco’s supply becomes adequate - the May 2024 line morphs into the June 2011 line? Because of all those embedded sources of demand I described regarding Los Angeles?

I suppose we’re about to see a natural experiment.

I think we can say 2 things about San Francisco, too:

San Francisco housing is in a deep cyclical decline, not a supply recovery. So it is not currently an example of how additional supply could quickly bring down home prices.

Even as deep as its cyclical decline has been, San Francisco average nominal home prices are still generally positive over most time frames. Very short-lived cyclical reversals (like in Austin recently) and epic, nation-wide, rabid credit shocks that are imposed for years (like in 2008), can cause disruptive contractions in nominal home prices. Otherwise, that is something that doesn’t really happen. There is a reason why buyers in the 2000s believed, to Robert Shiller’s chagrin, that home prices don’t go down. Because it’s mostly true.

This is a nicely reasoned and explained analysis. Thanks for sharing it.

I lived in Miami in 2006 and the speculation was rampant. So I was around younger people in a professional degree program that had no interest in living permanently in Miami and they were taking on huge amounts of student loans AND they were considering taking out a mortgage on a condo to flip to make a quick buck. I also happened to be around and older guy that did buy a new condo earlier in the decade and by 2007 he was already trying to sue the builder because the condo measurements were slightly off.

When I look at various metrics of those years one stands out and that is tax revenue as a percentage of GDP. So under Bush we had record low tax revenue as a percentage of GDP in a growing economy in his first term…and I wonder how much of the Housing Bubble was just “dumb money” being pumped into a dysfunctional economy?? So credit card debt spiked and student loans spiked and mortgage debt spiked…why weren’t people focused on getting a career job with a salary as a way to make money??