I’ve been playing around with the data from some of my Mercatus papers. In the paper where I reviewed the causes of the pre-2008 bubble, following the convention of the existing literature, I analyzed changes over periods of time - 2002-2006 and 2006-2010.

But, it is possible to look at the effects of different variables in a time series. So I was charting the correlations of various variables with home prices over time.

One of the arguments I make is that the private mortgage lending boom that very abruptly came and went between late 2003 and mid-2007 was not nearly as important as it has been given blame for in rising home prices. And, the crackdown on mortgage access after 2007, which has been widely ignored or excused, was much more important.

One of the variables I used in my analysis was the market share of FHA in each ZIP code in 2002. This is meant to serve as a general proxy for the dependence of that ZIP code on marginal lending - a pre-existing condition before the rise of the subprime boom to identify each ZIP code with as a constant.

For each month, I regressed the 3 month change in home prices against income, density, denial rate on new mortgages, non-occupant mortgage activity, and FHA share (all the mortgage-related variables are from 2002). Figure 1 shows the association between FHA market share and 3 month home price trends in Detroit.

It’s nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing, and then BOOM, 2008. All of a sudden, quarter after quarter credit-sensitive ZIP codes are losing ground fast.

One thing I should make clear is that this isn’t measuring the change in FHA lending. FHA lending actually increased quite a bit after 2007. There was a lot of market share substitution. The private securitization markets disappeared as quickly as they had come, and so FHA and the GSEs had to pick up the slack. But, the net result was a sharp tightening of credit. The borrowers that the GSEs and FHA were serving after 2007 were a much more high-tier set, with much lower default risk, than really at any time in recent history including the time before the subprime boom.

This isn’t measuring a change in FHA activity. It’s measuring home prices in credit-sensitive neighborhoods.

So, again, to recap, the picture in Figure 1 suggests no credit bubble at all, then a devastating collapse.

In Figure 2, I have binned the ZIP codes within each metro area roughly into quartiles, and here I am showing the ZIP codes with the highest FHA market share in 2002 and the lowest.

Now, here, you can see that in Detroit, there was a small difference in price appreciation in credit-sensitive ZIP codes before 2008. And, in the existing literature, that is roughly the scale that they purport to quantify. By treating the difference between cities as a control variable to be ignored, statistically, you can explain that little tiny difference in Detroit from 2000 to 2008 and then conclude that you figured out the whole thing.

The problem is that by the end of 2007, Detroit was well into negative territory across the metro area. The only reason anyone wanted to tighten (either monetary policy or lending standards) after 2007 was because of the outlier cities. So, it’s a bit of a political-academic two step going on here.

I don’t think this is any kind of conspiracy. I just think that “a credit bubble caused a housing bubble” was the predesignated conclusion, and mental gymnastics come very easily to us when we’re engaged in confirmation bias. It’s just an easy switch having to do with what we double-check and what we consider outlier information.

The academics could explain the difference between those two lines in Detroit, and that gave us the resolve to ignore the initial collapse in Detroit in order to “normalize” LA.

Anyway, in Figure 3, you can see that sub-760 credit scores had borrowed more than 2% of the value of US residential real estate dependably in all quarters until the 4th quarter of 2007, after which it quickly dropped to 1% where it has remained.

You can see in Figures 1 and 2 that when the credit was cut off, the downslope of the credit-sensitive ZIP codes in all cities steepened.

This post is mostly a comparison of LA and Detroit, but I had to include Phoenix in Figure 2. One of the poster-children of the credit bubble. Absolutely no difference in price trends in Phoenix between credit-sensitive ZIP codes and less credit-sensitive ZIP codes during the boom. And, notice in the legend of Figure 2 that FHA market share was much higher in 2002 in Phoenix than in the other cities. In the most credit sensitive quartile in Phoenix, FHA market share was above 30%.

Anyway, as I have mentioned before, the literature that blames credit for the housing volatility rests on the idea that homes were overbuilt in places where supply wasn’t obstructed, so there were places like LA where prices went up and then down, and places like Detroit where construction increased and then prices went down.

Again, as I have mentioned many times, literally nobody cared to spend even the slightest effort checking on this. As you can see in Figure 4, building increased more in LA than it did in Detroit.

There are 2 glaring problems with the intuition here. First, in cities like Detroit, even at the peak of construction in 2005, there was, stretching estimates as much as possible, an accumulation of cyclically higher building of 1% or 2% of the local housing stock. There is no model on God’s green earth that gets you from that to a 50%+ price contraction.

Secondly, as you can see in Figure 4, construction in Detroit collapsed to negligible levels between 2005 and 2008. When prices collapsed in credit-sensitive ZIP codes in 2008, there had been very little building for quite some time.

Rent

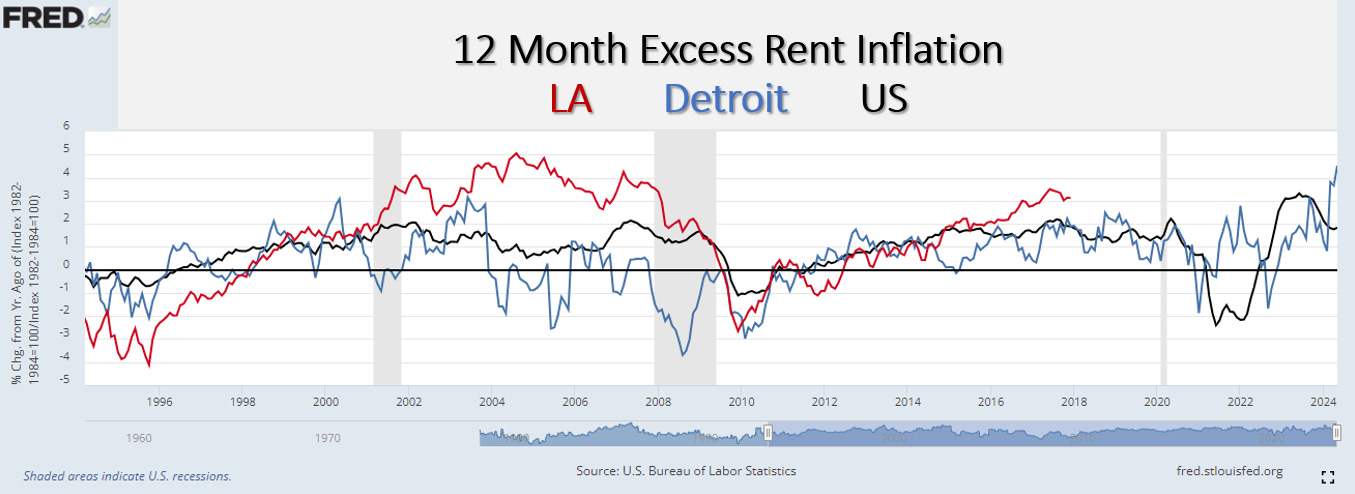

When building in LA was deeply inadequate in the 2000s, rent inflation was exceedingly high. Figure 5 shows rent inflation relative to core CPI inflation. Rent inflation should move around zero over time. In Detroit it was before 2008. Building homes was keeping rents stable in Detroit. Obstructing homes in LA was pushing rents higher. That’s the cause of the differences in Figure 2 before 2008.

Then, after 2008, the credit crackdown killed off new building in Detroit while building in LA returned to its low pre-2008 levels. Since then, both cities have perennially had excess rent inflation. When housing is inadequate, rents rise the most in the poorest neighborhoods, and so now home prices in the ZIP codes that were most devastated in 2008 have risen above the trends in the rest of the region (Figure 2) because of the regressive effects of rent inflation.

A lot of this is review for EHT readers, but I thought the new visuals in Figures 1 and 2 were worth sharing. And, I hope these figures provide a visual outline for the layers of distress that have been imposed on working class Americans.

Layer 1

Before 2008, millions of families had to pack up and leave places like LA and move to places like Phoenix because places like LA won’t permit adequate new housing. Millions of economic refugees were created.

Layer 2

In 2008, mortgage credit was cut off to millions of families. Roughly $5 trillion in net worth was destroyed. In places like Detroit where owning a home in a lower-middle class neighborhood was something families strived for in multi-generational efforts for a better life, their savings were obliterated. Many lost those homes. Most of that potential has been eliminated. They are renters now, we insist.

Layer 3

For decades, families had used that credit to move aspirationally to places like Phoenix. That was now greatly hampered. There used to be a set of cities growing at 3% or more annually, because Americans preferred to live in those cities and saw opportunities there. Those cities may still have opportunities and may still be preferred, but except for Austin, there really aren’t any high-growth cities any more.

Layer 4

The effects of these damages are somewhat hidden because millions of American households are still hanging on to homes that they own but that they would not be allowed to buy with a mortgage under current conditions. Many other Americans have cut back on housing size and quality in order to try to maintain some budgetary control.

Also, take a look at Figure 3. When interest rates go down, homeowners frequently refinance to take advantage of the terms of American fixed-rate mortgages. Some homeowners might use those conditions to take some cash out of their homes to handle family budgetary issues. That is especially important for families with lower incomes, lower credit scores, etc. They need more flexibility on the margin.

In 2003, there was a refi boom because mortgage rates had declined. Notice that there was a bulge of new borrowing then, and it was broad across the market - both lower an higher credit scores. There was another refi boom in 2020 and 2021. Of course, we are all familiar with the stories of homeowners who today are immune to rising interest rates because they refinanced during that time and now they can live in their homes on favorable terms. Those are the haves. In Figure 3 you can see that during 2020 and 2021, borrowers with higher credit scores took out a larger amount of mortgages than at any time since 1999.

The have nots did not. They could not. We won’t let them. To the extent that there are still grandfathered in homeowners who wouldn’t qualify under today’s standards, they are not allowed to take advantage of low rates or to extract some cash from their homes to cover living expenses. No refi booms for them.

Layer 5

The rising rents that had created economic refugees from a few cities like LA have now infected every city. But now, there is nowhere to move to. Since 2015, America is increasingly dividing into haves and have-nots. The haves get mortgages and live with comfortable housing costs. The have-nots don’t, and the difference has created what surely must be the most extreme regressive divergence in incomes and quality of life that this country has seen outside of war time.

Conclusion

Each of these calamities, individually, would fuel social unrest:

Local housing so obstructed in some regions that costs double.

So many refugees fleeing that that costs double even in the places they are fleeing to.

Rates of internal migration halving within a generation.

Home values halving for working class owners.

Then housing costs doubling from rising rents for families who can’t be owners.

Those are each signals large enough that historians and archaeologists in the future would consider those individual points, on their own, to be a sign of a society under stress.

There must be millions of American families that have run the gauntlet through several of these layers. A worker in LA who couldn’t make ends meet any more in 2002. They moved to Phoenix where they managed to get a job in construction and with much more affordable housing, purchased their own home. They lost it in 2010 when they were laid off and the home was in negative equity. Then, over the following decade, they kept moving into smaller apartments, letting kids and grandkids move back in with them, all the while wondering how long they could keep up with rising rents.

How many versions of this story must there be? Like Rocky Balboa in round 15. How much can they take?

It’s hard to drive around Phoenix these days. It breaks my heart. But the homeless encampments are just the tip of the iceberg. Just the visible fraction of a deeply diseased country.

And, yet, for anyone who could affect change, the story I laid out here is a non-starter. A set of confabulations that contradicts the things they think we all know. We are more likely to make new rentals illegal - to add another layer - than we are to reverse the mortgage exclusions that have caused so much harm.

Just in the last few days, the Biden administration has released yet another housing plan that is a mixture of misguided policies known to make things worse (rent control) and a mix of federal nudges toward more supply, which are well-considered but unlikely to amount to much.

Trump has appointed J.D. Vance as his nominee for Vice President. Vance has variously suggested fixes for high housing costs that include going after rent management algorithms, blocking Wall Street investment into new single-family homes, and deporting millions of immigrants. Scapegoating irrelevancies, policies that would add even more cruel new layers to the damages listed above, with additional casual cruelties layered on top of it all.

Unwinding the mortgage knots I outlined above isn’t even on the radar, even though it could probably be at least partially reversed with quiet executive branch underwriting changes at the agencies. At least, in the meantime, YIMBYs at the local and state level are accumulating a large mountain of small wins that land use reform will require.

It’s a race between our better natures and our worst. Let’s hope the better wins out in committee rooms and council chambers while the worst is dominating the cameras and the party convention stages.

Over at Marginal Revolution there's a brief description and a link to research on how legal action against large banks prompted their exit from FHA lending. "We had to destroy the village in order to save it."

Once again this is anecdotal. I live in a very desirable city in which rents exploded even before the pandemic. A big reason for rent increase has been STRs because my city is building apartments but they are for wealthy younger people whose parents are probably helping them out. So the old rental property neighborhoods have been gentrified and the newer rental properties are big buildings with pools and gyms for people that drink White Claw.

I will add that I just happened to live in Orlando on the south side of the city near Kissimmee. So this was around 2013 and school buses were still picking up at the old motels that were built long ago to serve Disney World and then became flop houses. I actually know someone that had access to cheap credit around that time and he was buying up empty homes in good Orlando neighborhoods at a fraction of the 2006 highs. So only in America would we shove families into crappy motels while perfectly good homes sit empty!