There is a pretty typical taxonomy, I think, of reactions to issues that have to do with balancing relative rights:

There isn’t a problem.

The current beneficiaries are justified in defending the status quo.

It’s a state of nature. There’s nothing to be done about it.

Those who are burdened just need to be realistic and deal with it.

It’s a shame, but wattaryagonnado?

In housing, there are examples of NIMBYs all along that range of reactions. For some, they are beneficiaries of the status quo, or they somehow identify with the beneficiaries. Or, they may simply have an intuition for defending the status quo. It is interesting to me how often people who really seem to have no connection to or motivation for defending the status quo will still settle into one of these positions. “Well, there’s just too many people.” or “Of course every 20-something can’t just expect to buy a Beverly Hills compound straight out of high school. You have to work up to that. My generation understood that.” These seemingly world-wise intuitions can gurgle up very easily with just a bit of naivete and a dose of status quo bias.

I write all of this knowing that over the course of my life, I have settled on this range of reactions on various issues, and, if I hadn’t happened to have initiated a personal study of this issue in 2015 for non-policy-related purposes, which eventually led me to where I am, I might have naively and smugly settled there on this issue too. (I’m not saying that everyone that makes these statements is smug. But I almost certainly would have been.)

Anyway, it is odd to me how commonly conservative leaning or market-supporting folks - either in finance, economics, or policy circles - take these positions. This should be an easy one. The administrative state is clearly getting in the way of commercial - and even personal - decisions. In many cases, the reasons for the obstruction, as stated, are trivial or ridiculous. It’s like defending transportation boards, excessive licensing, an aggressive FDA, Covid related mandates, etc. Market supporters should be natural YIMBYs.

I think there are several reasons for this. The secular looks cyclical, and so there is a tendency to view people buying into the top of a cycle as foolish and undisciplined. And since prices are especially inflated, buyers seem especially foolish. Also, the involvement of public and quasi-public institutions in the housing market (Fannie & Freddie, FHA, HUD, etc.) makes it possible to blame all demand, on the margin, on public influence. And, the popularity of Austrian-style business cycle theory, in all areas - finance, econ, and political policy - bundles all of it up into a seemingly coherent package of publicly fueled foolish excess that inevitably crumbles. The saliency of that pushes all of the enthusiasm for “getting the government out of housing” toward demand suppression instead of supply advocacy.

I would argue, empirically, against many of the complaints about public over-stimulation of housing. But, more importantly, these positions frequently work against the supply issue. In fact, when I get my pique up, I can make the case that demand suppression has done more to damage the real production of new housing than the NIMBYs could have ever dreamed of.

But, in today’s post, I just want to make a limited point. Let’s accept everything above. Let’s accept one of the points on the reaction list that says some version of, “Look, nice places are expensive. People have a right to say what gets built around them. LA just doesn’t have room for more people.” Etc. Etc. Etc. So, the current population of the expensive cities is an unchangeable state of nature and their prices reflect that.

If that is the case, then, sure, cyclical home price trends on the margin are due to “greater fools”, subsidies (whatever you imagine them to be), speculation, interest rates (I’m really forcing myself to accept some stipulations here), etc. But that margin is miniscule compared to the stipulation I have already accepted - that the high prices in the Closed Access cities are a state of nature.

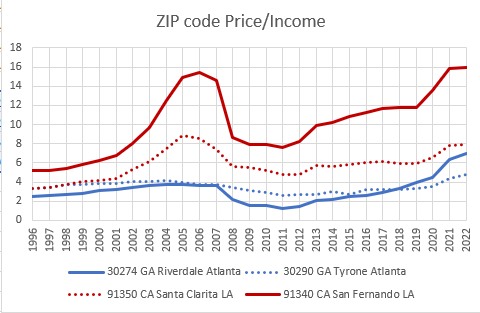

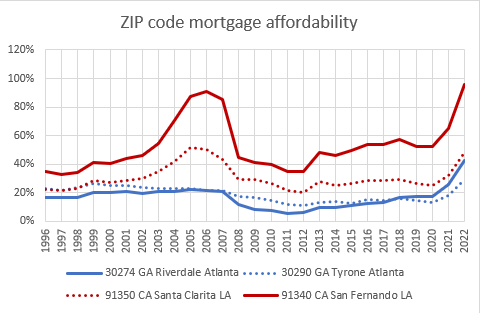

Here are charts of incomes, price/income ratios, and mortgage affordability (% of income required to buy the median home with the average ZIP code income at 80% LTV with the average 30 year mortgage rate) for 2 ZIP codes in LA and in Atlanta. One a high tier area and one a low tier area.

I just grabbed these relatively randomly from my database. But, I will say, it is hard to find a low tier ZIP code in LA that doesn’t outpace the income of the typical low tier ZIP code in other cities. That’s gentrification and its side effects. That’s the result of the upward filtering of the existing housing stock in a housing deprived city. That’s the result of countless decisions households must make in which income and the incomes of your neighbors and others who are seeking affordable housing is the primary motivating force. Much of that increase isn’t because locals in LA are doing great. It’s because the locals who aren’t doing great systematically move away each year and are replaced locally by others who have self-selected to spend more on housing than the leavers were willing to. The best way to be able to do that is to have more income to spend. But, struggling to get by on less while most of your paycheck goes to rent is also commonplace.

That’s one of the things that makes straightforward analysis of this issue difficult. It’s easy to misinterpret that as a sign of LA’s “success”. But, we are stipulating that this is a state of nature. Thousands of intra-national refugees is just the way things are.

Here is what price/income levels look like in these 4 ZIP codes. So, go to town with your demand-side explanations. Blame “greater fools”, private equity, subprime borrowers, speculators, whatever, for, say, the rise in low tier Atlanta from 3x to 4x price/income levels from the 1990s to 2005, or from 4x to 7x from 2019 to 2022. But that is only about 10-25% of the difference between low tier Atlanta and low tier Los Angeles - the difference that is just a state of nature.

Accepting the supply status quo means accepting 75% of what’s happening here. No amount of demand suppression is going to get rid of that. And when we tried really, really hard to do it - to pound away at the prices of these places until the average of them seemed normal compared to the preceding century, what we ended up with was low tier Atlanta at less than 2x income and low tier Los Angeles still at 8x. The only way to make the average look normal is to absolutely obliterate places like low tier Atlanta.

Atlanta was much less normal in 2011 than it had been in 2005. And, now prices are higher than ever in Atlanta because the result of the damage has been relentlessly, unprecedented rising rents in places like low tier Atlanta. And, so, now we’re left with the dilemma. Do we talk ourselves into thinking that high prices in Atlanta are just a state of nature? Do we blame the remaining institutions who are still capable of buying low tier homes in Atlanta with the blessing of regulators? Is this some sort of non-leveraged Minsky cycle?

The explanations will have to be increasingly inchorent. It is fundamentally incoherent to base demand-side opinions on national averages of these areas. Those wide swings in valuations in LA are just part of a slowing and accelerating process of getting the poor folk to hurt enough to leave. How exactly are we going to decide when that pace is fast enough to be foolish? And, furthermore, what does any of it have to do with housing in Atlanta? Why should you care what the “average US home price” is? That’s like averaging the population of stray cats and the storage capacity of hard drives. It isn’t a coherent set of things that should be averaged.

I recently saw a Robert Shiller interview from 2013 where he said that housing wouldn’t get as inflated as it had been in 2005 because that was just a fad. The “greater fools” had learned their lessons. He was wrong about that… Well, he was right that there wouldn’t be a faddish housing bubble driven by foolish spendthrifts. At its base, what he was wrong about was thinking that’s what happened the first time.

Finally, here is mortgage affordability. First, I must note here that if mortgage rates drove home prices at all, the lines in Figure 3 would be more stable than the lines in Figure 2. All the reports these days of the coming decline in home prices because the mortgage payment on a given house is xxx% higher than it would have been a year ago are the triumph of theory over empirical history. Price/income ratios (Figure 2) have never been particularly sensitive to mortgage rates. That’s true in LA 2022 vs LA 1996, low end LA vs high end LA, or LA vs Atlanta. There is just no dimension to look at here where empirical history will support an expectation of some stable mean in mortgage affordability.

I think there is a reasonable argument that can be made that the rise in low tier price/income ratios in Atlanta from 1996 to 2002 could be primarily explained by the decline in mortgage rates over that period. That’s the sort of pattern you would expect to see when mortgage rates are dominating the market - changing price/income ratios and flat mortgage affordability. Since these charts have been scaled to include other ZIP codes that reflect other factors in the marketplace, you might need a microscope to pick that out. But, it is definitely a possibility in the pre-2002 data.

Second, mortgage affordability that keeps rising to 50% or 100% or more of income in LA is not being driven by mortgage access. Markets know things. They are information aggregators. And, mainly what they know about ZIP code 91340 San Fernando, California is that the “state of nature” of LA real estate means that eventually most of the residents who would have to spend all of their incomes to own the homes they are living in will suffer enough to choose displacement over community. Those aren’t prices for them. They are prices for their replacements. We are stipulating that that is a state of nature. Again, the price of those homes relative to the incomes of their tenants is not a coherent basis for having an opinion about demand, money, or credit. The price of those homes has little to do with the incomes of the people that will eventually be moving out of them.

So, the long and short of it is, if you’re somewhere on that range of reactions to our housing market, where the supply issue in LA is just something we have to live with, then your reaction should lead to a pro-demand position. Stimulate building everywhere else. Support mortgage lending to families who want to live anywhere else. Subsidize moving expenses for those San Fernando families to move anywhere else and spare them the years of hanging on to their hedonic housing treadmill. But, if you think LA’s situation is just a state of nature, then there really is no reason to keep enforcing austerity in Atlanta as a result of it.