What Homes Are Missing (by Tenure)?

Previously, I have estimated the deviation in the trend of adults per home, trends in homeownership, and trends in the types of homes being constructed. This post is just another stab at that with some slightly different visuals.

Migration and Homeownership

On household formation and homeownership, it is important, obviously, to control for demographics. Older households are more likely to be homeowners, so there has been a substantial upward drift in the homeownership rate, all else held equal. For more careful analysis, education, marriage, and a host of other controls can be useful too, though age is the big one.

Another potential control issue occurred to me. There has been a massive necessary outmigration out of areas that refuse to permit new housing and into areas that allow it. That migration is moderated through economic stress and rising costs. Where costs rise, there are more capital constraints that make home buying difficult.

Also, city-building used to be legal, but in the 20th century, locals gained the political ability to block it. The more neighbors there are, the more veto points there are to new building. So, ironically, the localities where city-building has been blocked the most are the localities that were more urban to begin with.

Dense places are more expensive because they permit fewer homes under the new political norms. This creates a spurious correlation between density and housing costs which has led to an overemphasis on agglomeration value and the costs of density. But, that turns the causality on its head. The expensive cities aren’t expensive because building is expensive. They are expensive because they aren’t building. It is true that there is agglomeration value and that dense building is more expensive. But those ceased to be the marginal factors in urban housing expenses long ago.

Anyway, my point is that the expensive regions are the pre-existing urban centers where the legacy stock of housing tends to be multi-unit and rental focused.

So, there is a surprising variation in homeownership rates across the country. Homeownership in New York City tends to be in the 20-30% range. In suburban Nashville, it’s 70-80%.

Families have been moving from low-ownership to high-ownership regions mostly because the low-ownership regions block housing. And they move from low-ownership city-centers to high-ownership suburbs for the same reason. The homeownership rate in Los Angeles County is less than 50%, and in Riverside County it’s nearly 70%.

(Side note: How well does the “homevoter” hypothesis sit with this fact?)

Anyhoo, I wondered how much of an effect this has on the national homeownership rate. Using county level homeownership rates, Figure 1 tracks how much the national homeownership rate would have changed since 1980 if the homeownership rate had remained stable in every county.

The compositional shift from migration to counties where homeownership is more accessible may have boosted the national homeownership rate by about 0.5%. Not huge, but not nothing. It would probably be more like 1% by now, if the housing bust hadn’t put the brakes on regional migration after 2008.

Homes per capita

Since the mid-20th century, household size has fallen. Mostly, that has been due to the decline in the number of children in the typical family. But there has also been a slight but steady decline in adults per household. The decline was faster in the early-20th century. Then, from the 1960s to the 2000s, it declined, annually, by about 0.005 adults per household. There were about 2.1 adults per occupied household in the early 1960s, and it declined to about 1.9 adults before the Great Recession.

Then, the decline stopped.

Figure 2 shows the deviation from the long-term trend in household size. The difference amounts to well over 10 million units.

There is a discontinuity in some of the data in 2000 because of some Census Bureau revisions, so the remaining figures will just be limited to the years since 2000. Figure 3 shows how many homes we have (blue), how many we would have if household size had continued along the same trends (black), and how many homes we would have if population growth and household size had continued along historical trends (red). Here, I’m using slightly different data (total population 16 and over from the current population survey), so the numbers are a little different than in Figure 2, but they tell the same basic story.

Trends in Housing by Tenure

Curiously, the decline in housing production has happened in waves, differentiated by tenure, as shown in figure 4. Before 2008, rentals were flat and owned-units increased. Then, rentals increased and owned units were flat. Then, rentals went flat again and owned units increased again. And, finally, in the last couple of years, both have started to trend up proportionately.

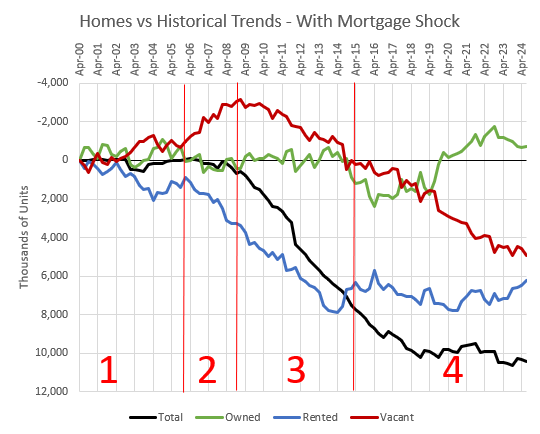

In Figure 5, I have plotted the change in owned, rented, and vacant housing units relative to long-term trends. Basically, the distance between the black and blue lines in Figure 3, disaggregated by tenure. I think it is interesting to consider the different periods.

Phase 1 is the 2000s boom period. You may feel like this is odd. Wasn’t that a period of massive overbuilding? Wasn’t the boom a deviation from trends that necessitated a national financial crisis?

Mostly, this is just a product the scale of the post-2008 crisis.

From 2000 to 2005, there was a very moderate building boom. There was a shift from rental housing to owned housing, and a rise in vacancies. (The choice to benchmark to 2000 is somewhat arbitrary here. The vacancy rate in 2004 and 2005 was, plausibly, near what we should consider neutral.)

Anyway, at the time, this was considered a big deal. Figure 6 is an estimate of annualized housing production from John Taylor’s speech to the Federal Reserve at Jackson Hole in 2007. He was very concerned that they had pushed interest rates too low and had triggered a disruptive building boom. His chart asserts that the appropriate amount of building was about a million units lower than the amount of building that happened before 2007. The scale of the deviations he was concerned about is in line with the deviations in Phase 1 of Figure 5.

I’d say one important measure of the relevancy of any economics thought leader is how much observational focus they put on correcting the trend deviations in Phase 1 versus the deviations in the other phases.

Phase 2 is especially telling. Between 2005 and the financial crisis in late 2008, total units produced was still pretty close to trend. There had been a deep cut in housing starts, that had begun in early 2006. That is how forgiving these trend deviations are. If housing starts had turned around after the September 2008 crisis, it would have been the deepest contraction in housing construction in decades, and it would have barely been a blip on the radar, in terms of total production numbers.

During that period, there were countervailing trends in vacancies and owned homes. About 3 million more vacant units and fewer owned units. There was no oversupply. The vacancies were the result of frictions in the marketplace. There were empty homes with willing tenants, but no able buyers. This was the first phase of the moral panic.

Phase 3 was the more comprehensive consequence of the moral panic. Millions of households were locked out of mortgage access. Millions lost their homes to foreclosure.

Some of them transitioned to new rentals. Some of them transitioned to formerly vacant stock.

In Phase 4, the decline in owned-units bottomed out. Vacancies continued to decline, but rental units stopped rising. In Phase 4, owners have been poaching units from both the rental stock and the vacant stock. The main deviation from trend in Phase 4 has been to prevent potential renters from forming new households.

In a way, the deviations from trend in Figure 6 are misleading. The mortgage shock necessitated a sharp trend shift.

I’m just tossing out a guesstimate here. But, let’s say 10 million households lost access to mortgage funding in Phase 2 and 3. That’s a one-time shock to the long term trends in tenancy, adding 10 million renters and subtracting 10 million owners.

Figure 7 shows the actual number of homes, the neutral trend based on long-term household size and tenancy trends, and the neutral trend based on long-term trends with a one-time mortgage shock.

Mortgaged homebuying from 2008 until recently was very advantageous to renting. Affordability was not a factor in driving down the number of owned homes. Affordability should have been a tailwind. The decline in owned homes after 2005 was due to hard obstructions to mortgage access for advantageous purchases.

Figure 8 shows the deviations from trend, after adding the mortgage shock estimate.

Using this population data gives a somewhat smaller total than my other estimates from previous posts. These measures suggest a shortage of about 10 million units. (Even this estimate is several million units higher than any other estimate I have seen, except for one by the JEC. The JEC may be a little on the high side. All the others are clearly wrong. By the time it is clear that all the other estimates are far too low, we will have better data to estimate how many millions of additional units above their estimates will be required to supply housing enough to fully reverse excess rent inflation.)

This estimate calls for about 6 million households in rental units and about 5 million new vacant units. Many vacant units are also intended to be rentals.

This is part of the thesis for the coming surge in single-family build-to-rent. There is pent up demand for nearly 10 million rental units (including vacant units), and municipalities aren’t anywhere close to being willing to allow that hole to be filled with multi-family homes.

There isn’t a natural market for single-family build-to-rent. Without those municipal obstructions, many more households would live in multi-family buildings. Without the mortgage moral panic, many more households would own single-family homes. But, it’s all that is currently allowed to fill the gap.

For any individual project, there is a lot to consider to know if a project will “pencil”. But, in the aggregate, the natural forces of demand pulling these trends back to neutral are strong. These deviations are unprecedented.

Another thing to keep in mind is that for 14 years, vacancies have been declining by half a million units annually, relative to trend. That is unsustainable, and in fact, some vacancy categories are probably at their functional minimum.

I have noted before that we have been harvesting about a quarter million vacancies annually. So, we have to increase production by that much just to make up for that. But, in a functional, sustainable market, we would also be adding a couple hundred thousand vacant units each year, in proportion to a growing housing stock.

The total number of vacancies has stabilized in recent years, but the trend in Figure 7 continues to decline because the number of vacancies in a sustainable, functional market would be rising slowly, even if we didn’t have a shortage.

In short, I can’t say that every potential new rental home will be profitable, but I can say that the number of potential new rental homes is more than we are capable of building, and will be for some time. There may be millions of projects that aren’t economical under current costs, rent trends, and borrowing conditions. But if your project doesn’t pencil, it’s because someone else’s did, and your cost of money and materials reflects their utilization of them.

I hope I’m wrong, but I tentatively expect that the demand for these new homes will trigger such a noticeable supply response that our dependably sadistic electorate will demand that we stop it. I hope that takes a couple of years so that the homebuilders are fairly valued, based on current operations, before they succumb to our next, and final, panic. And I hope it never happens for the sake of working class American families and for a return to functional politics.

Note: There were large variations due to survey error during Covid, which I have smoothed out in the figures above.

My gut reaction is to agree that the "sadistic electorate" will react negatively to more housing construction, but as usual I think this will continue to be a regionally specific phenomenon. As Nolan Grey puts it: "Red states build, blue states don't" and I think this trend will persist even if deportations mess up labor markets in Southern boom cities.

Although not the major focus of your post, I appreciated your paragraph debunking the "density is too expensive" argument that crops up in NIMBY camps. While it's true that life/safety building codes and construction physics make large buildings marginally more costly to construct, the major impediment is local regulations that drive up planning time and soft costs. Multi-unit builders could make money anywhere if they were given the opportunity to build at scale in response to market demand.

Are you saying that smart developers with a long term focus should find a way to construct multi-family or single family over build-to-rent, since build-to-rent only has adequate demand currently due to regulation and lack of mortgage access restricting multi and single family building?

In other words, when demand dynamics return to "normal", will build-to-rent still make sense to develop?