The YIMBY Housing Correction: Rent

In a recent post, I argued that neither cyclical corrections nor rising interest rates make good explanations for recent trends in home prices. And, furthermore, one explanation that would fit the data is that YIMBY gains in California could already be affecting home prices there.

In a recent paper at Mercatus, I pointed out that rising home prices in general recently and over the longer term have been driven by rising rents.

What are the trends in rents? And what do they say about the California market?

First, here is a comparison of rent/income in Phoenix and Los Angeles in 2015 and today. Price/rent ratios add information about expectations that I think makes the price/income ratio a better indicator of supply conditions (shown in the previous post), in general, but rent/income does present a similar pattern. Where housing supply is constrained, rents go up the most for residents with lower incomes. On the Price/Income pattern, Phoenix still has a lot of catching up to do to be as bad as Los Angeles, but as you can see here, in terms of Rent/Income, they are now more similar. LA has been bad for a while while Phoenix is more recently bad.

I think one way you have to think about this is that low end rents rise initially when cities become supply deprived. (Unfortunately, most major metro areas are now.) But, at some level (basically the level Los Angeles now is at), you reach a terminal position. Normal households can’t spend 120% of income on rent. So, once some significant portion of the city is spending more than half their incomes on rent, there is no way for rents to continue to rise on the same residents. The way rents rise from there is that residents must migrate away to make room for residents with higher incomes. So, the rent/income line is steepening in Phoenix while in LA, increasingly, it moves to the right, as Americans segregate into and out of LA by income. Once a city is in LA’s condition, population tends to be countercyclical because economic growth is associated with an exodus of households with lower incomes.

Of course, if your economic ideological expectation is that capitalism always operates in this way, then LA’s condition doesn’t seem anomalous at all. It seems natural, and it seems to confirm your complaints. And, I suspect this leads to the intransigence among some tenant rights activists, etc., about fixing the supply problem, because the supply problem reinforces their criticism of capitalism and their ideological self-identity. They think LA has a capitalism problem, not a housing problem, and to be convinced otherwise requires not only accepting facts on the ground about the housing market but also rejecting a much more broad set of beliefs about the way the world works in general. The myth that under capitalism, growth requires that the poor get poorer is not a myth in housing deprived LA.

In terms of recent trend shifts, in the previous post, I noted that prices still continue to rise in most metros, as they have throughout the Covid period. (You should read that post first, where you will see charts of price trends, if you haven’t already.) Rather than seeing a broad reversal in cyclical trends, there has just been a regional downshift in the west. Rents differ from prices in that they do show a very weak cyclical trend shift (recent declines are slightly correlated with previous increases). Rent trends are similar to price trends in that there has been a recent decline associated with the west, although the shift in rents has been much weaker than the shift in prices. In both prices and rents, there is no evidence of a recent move away from cities with higher rents or prices. Figure 2 compares rent changes from the previous 2 years to recent rent changes since May. There is no decline in rents, no broad reversal of previous gains (which would take the form of a negatively sloped linear pattern), and just a slight negative bias in the west.

Figure 3 compares the expected change in rents correlated with previous changes in rents and with being in the west to actual recent changes in rents. The equivalent chart to Figure 3 in the post about prices had a much more barbell shaped set of outcomes, with the west cities far to the left and other cities up and to the right. There is still a difference here, but not such a bifurcation. Also, notice in Figure 3 that, among the western cities, the coastal California cities have had the highest rent inflation recently. So, definitely, the reason they are price outliers is not that they are rent outliers in recent trends. Prices are declining while rent inflation is pretty average.

This is very clear if we compare changes in rents with changes in prices. In Figure 4, the x-axis is the change in rents from March 2020-May 2022, and the y-axis is the change in prices over the same period. As you can see, and as I hammer home here frequently, supply is driving rents which is driving prices. It is very easy to intuit from Figure 4 why Austin might be a singular outlier in recent cyclical reversals of price trends, because for the past 2 years it was an outlier in terms of prices vs. rents. (Aren’t you shocked that Texas’ unique limit on cash out refinancing didn’t prevent this?!)

Now, look at Figure 5, which compares rent and price changes over the past 4 months. Here, the most negative relative price changes are generally from Austin and the coastal California cities. Austin might be reasonably called a cyclical correction. As I pondered in the previous post, could the coastal California metros be called a secular correction? A correction in prices being driven by expectations of future supply relief, even if supply isn’t yet lowering rents? These trends fit that narrative.

It is harder to say whether these trends could be explained by some sort of regional economic contraction, a slowdown in work-from-home shifts, or other standard supply and demand stories. That is because the housing supply conditions in the deprived cities create such an odd circumstance. General economic growth leads to outmigration from the housing deprived cities and some of their local income growth is due to that cyclical outmigration of residents with low incomes. So, the effect of a cyclical slowdown in California is mostly felt as a decrease in housing demand in other cities. What effect would a local economic slowdown have in the housing deprived cities? Normally we should expect population changes in a metropolitan area to be positively correlated with local economic conditions. I’m not sure how Los Angeles’ population would change if there was a localized economic contraction. Would it decline because of fewer inmigrants? How would that affect outmigration? How would it affect rents?

The existence of thousands of outmigrants likely serves as a floor on demand, willing to pay the current rent, but no more, creating a demand floor that might support current rent levels until enough new supply is created or demand from other households declines enough to fully reduce the flow of outmigration. Building thousands of units might avoid the displacement of thousands of households with lower incomes before it lowers rents much. If that happens, the non-displaced households will be mostly invisible. Tenant advocates (sic) will say that they were right all along and supply just attracts residents with high incomes without lowering rents. Hopefully, YIMBY momentum will strong enough if that happens that the complaints will be impotent.

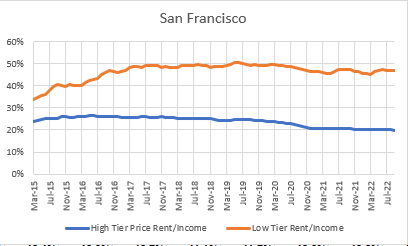

This appears to be what happened in San Francisco during the Covid period. When detailed migration statistics are available, we might find that net domestic migration from San Francisco didn’t change much during Covid, but that temporarily, residents with high incomes moved away, allowing residents with lower incomes to remain, albeit at still high rents. High end rents declined in San Francisco, but the difference between high end and low end rents remained about as steep.

Clearly, if more housing starts being constructed in San Francisco, thousands of low tier households will be able to remain with stable (though still high) rents rather than moving away. Rent/income levels might remain stable, but the denominator will be lower because there will be room for the previously displaced families. It is certainly too early to expect declining rents from future supply relief, but even when the relief comes, declining rents might be a lagging result that requires much higher rates of construction. Yet it would still be a victory for what remains of the California working class.

So, a recent negative price trend in California that is not strongly related to a negative rent trend could be evidence of the early benefits of YIMBY gains. I’m not sure what else it would be evidence of, though of course I haven’t thought of everything and these trends are still young.

Buckle up and keep watching.