The YIMBY housing correction

I have been posting skeptically about the role of rising interest rates and cyclical reversals in recent home price trends, in general. Last month, I noticed that price declines were oddly West-coast centered. Others have noticed that also. I speculated on Twitter that such regionally tilted data fit a localized supply story much better than it would fit an interest rate or a cycle reversal story. With new September numbers out from Zillow (God bless them), the Erdmann Housing Tracker is uniquely poised to entertain that hypothesis, and the answer seems to be a surprisingly strong “Yes”!

Just to give a very brief conceptual background on this, the basic foundation of the Erdmann Housing Tracker is that local constrained supply leaves a peculiar mark on a metropolitan area’s housing market. Figure 1 compares Los Angeles in 2021 with Phoenix in 2002 to highlight two extremes of supply conditions.

2021 LA is highly supply constrained. (High rents and prices, lots of outmigration of families with low incomes who claim housing costs are their motivation, etc.) 2002 Phoenix was a growing city without binding supply constraints. As you can see, at some very high income level where housing costs are almost purely determined by incomes, unconstrained by credit constraints, compromises on basic necessities, etc., home price/income ratios converge at a similar level. This is true across all cities. The costs of constrained supply fall systematically on families with lower incomes, and countless housing decisions across the metro area spread the financial burden so systematically that the relative price inflation across the metro area aligns quite linearly according to income. Basically, if you want to remain in a metro area that is determined to starve you of housing, the more financially vulnerable you are, the more financial pain you’ll have to be willing to swallow to stay there.

I will go into much more detail in a new paper that will be posted imminently at Mercatus. That basic model is the pretense for the Erdmann Housing Tracker and for the analysis that follows.

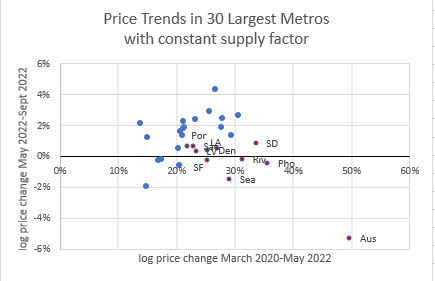

OK. So, if interest rates were causing prices to decline, that effect should be relatively universal. If a cyclical reversal was causing prices to decline, that effect should be negatively correlated with previous price appreciation. Figure 2 is a basic check on those intuitions. These are the 50 largest metro areas. The x-axis is the price appreciation from March 2020 to May 2022. The y-axis is the price appreciation from May to September 2022. I have highlighted western metros in red. (There is a nice dividing line down the eastern boundary of the Rockies that makes an easily definable “Western” set of markets, which it is easy to argue are driven by the convulsions of California migrations, tech sector cycles, etc. Originally, I was reticent about including Austin, because it isn’t quite so easy to include in such a basic geographical category, but clearly in this cycle, Austin is being driven by a lot of tech-related and West coast related migration, and so I decided it is reasonable to include it in the “Western” category.)

The West vs East divide is quite sharp. Interest rates would be associated with generally declining prices and a broad distribution of dots below the x-axis. Cycle reversals would be associated with a negatively sloped pattern. Yet, prices east of the Rockies continue to rise, in spite of rising interest rates. And, especially after noting the West-East divide, there is no indication of a general reversal of previous price appreciation.

Clearly, the primary issue at play here is something happening on the West coast. Normally, with this sort of evidence, you would look to some sort of regional recession. But, such price deviations in housing would normally only come after an extensive and obvious economic upheaval.

Some have suggested it is related to losses in shareholder equity. Possibly, but, again, it’s a bit of a stretch as a just-so story with such deep and regional price deviations. Others have suggested that it is related to remote work and a migration away from previously expensive markets.

In a regression of May-September price changes against 3 variables (the “West” dummy, March 2020-May 2022 price appreciation, and relative March 2020 price levels):

Being in the west is associated with a decline of 5.3%.

Price appreciation of 33% from March 2020-May 2022 (approximately the average) is associated with a continued increase of 2% since May. In other words, Covid-era price trends remain. They have not reversed.

There is no significant relationship between the starting price level and recent price changes.

Figure 3 compares the 4 month price appreciation predicted by those 3 variables and the actual price appreciation. There’s this big West-vs-East thing, then there is a bit of a continuation in the trends of the Covid/low rate-era, and then there is some noise that amounts to a minority of what remains to be explained.

So, there is something going on in the West. The Erdmann Housing Tracker can separate out the cyclical from the supply-induced changes. What does it tell us?

First, here’s a look at Atlanta. This is the price/income ratio for ZIP codes across Atlanta in May and in September. There are 2 trendlines here, though you may not quite be able to make that out. Basically all the cities in the bunch of blue dots in Figure 3 look like this. In 2022, prices have basically tracked incomes. Nothing is happening in home prices. (From March 2020, to May 2022, rising prices in Atlanta largely were due to higher prices at the low end - looking more like LA in Figure 1. That’s very common across cities, but that’s a topic for other posts.) The main current empirical issue with rising interest rates and declining home prices is that there isn’t really any evidence of it in most cities.

Next, let’s look at Austin. It is basically the one city where you could make either an interest rate or a cyclical reversal story. Of the major metros, it was the city with the largest cyclical impulse. In Austin, home prices across the income spectrum increased, and now home prices across the income spectrum are declining. Price changes since May look similar to Atlanta almost everywhere, but Austin stands out as an outlier.

Here are the 3 California coastal metros. They have very steep slopes in this price/income pattern. (Note the different scale on the y-axis compared to Austin and Atlanta.) San Francisco has had a little bit of a uniform decline, like Austin. But, all three metros have seen substantial flattening of price/incomes. Declining prices since May are mainly at the low end. Whereas Austin is an outlier confirming a broad housing reversal, the California cities are outliers signaling a supply-induced correction (which is the good kind!). Rent inflation reported by Zillow is also low in the California cities and generally in the west, since May. However, especially in the current environment, short term rent fluctuations are a complicated metric to interpret. Low rent inflation in the west could mean that there is some sort of regional economic slowdown at play, or it could mean that supply-side reforms are already helping. I wouldn’t have put many eggs in either of those baskets, but western rent inflation is running low since May nonetheless.

The California cities are true outliers here. The non-California cities with the most flattening in the price/income line are Denver, Phoenix, and Portland. Portland also has had recent YIMBY victories, so possibly its shift could also be attributed to expectations of loosening supply constraints. But, my main point here is that outside of California, these are the best examples of flattening price/income slopes since May, and they aren’t close to the scale of change we see in California. (Again, keep in mind that the slopes are so steep in California that I have to extend the scale of the y-axis, so the scale of change in the California charts is understated in comparison to the other cities. But, even with that difference, the recent improvement in low-end affordability in the California cities is clear.)

One last way I’ll look at this is to revisit Figure 2. Using the Erdmann Housing Tracker, I can track price changes within each metro area based on cyclical changes that move prices across the whole city (like in Austin, above). And, I can track changes in prices that are mainly due to supply constraints, which mostly raise costs for families with lower incomes. The coastal California cities are case studies in this process. The reason prices become unsustainably high is that people really don’t like to be displaced, and they will pay unreasonably high costs to avoid it as long as they can. So, a lack of adequate supply mostly leads to higher costs which are moderated only by the willingness of families to move away. Most families in coastal California that had very low incomes have already moved away, and the only ones who remain are the families that were willing to pay the highest price to stay. This is how you end up with such a dependably linear downward sloping price/income pattern. For years, families have been self-segregating into and out of California based on the amount of financial hardship they are willing to endure.

So, first, Figure 8 is a chart similar to Figure 2, but this tracks only cyclical price changes that are uniform across the city (a la Austin). The distance to the right on the x-axis is how much cyclical price appreciation there was from March 2020 to May 2022, and on the y-axis is the cyclical price appreciation since then. Here, Austin is the outlier, and the other cities show neither a general decline (below zero on the y-axis) nor a systematic reversal (a negative slope with high earlier appreciation being reversed by recent declines). The western cities are at the low end of the shapeless clump of dots, but they are not outliers.

Figure 9 shows the supply related changes. All cities have demonstrated steepening price/income slopes - low end units have gotten more expensive over the past couple of years (moved to the right). And, in general, low end homes have continued to become relatively more expensive since May (moved up). The exception is the California cities. The effect of supply (or supply expectations) has been negative on the nominal price of the average home in the California cities (except for Riverside). Basically, California is negative and the rest of the country is positive.

So, I can’t say that supply-side victories explain all of the price trend deviation since May. But, they explain much of it. As of September, you’ve got Austin, which is singularly telling a cyclical boom and bust story. You’ve got everywhere else, which is telling a story of a relative plateauing, but not a reversal, of a cycle, along with the continuation of a supply constraint problem. And, you’ve got California, which is more or less alone in reversing the supply constraint trend.

Let’s hope the California story continues.

Please share! And consider subscribing to stay abreast of these trends and to support my work to provide you with a unique understanding of American housing markets.

(PS. One technical note on Figures 8 & 9: Both charts include the relative change in valuation that is proportional to rising incomes, so the measures, in nominal terms, in both, will tend to be slightly positive.)

This could be a really good thing if it persists in California, which requires sustaining political momentum. Given that the majority of voters benefit from this I'm allowing myself to feel some optimism for continued reform.

Here in the Boston Metro area things are still messed up--no new supply, transaction volume in decline, and no price decreases in the high end market. Not sure how the rest of the region is, or where it's headed, but so far it's different than 2008ish.

"Sunk costs are such a large part of the cost of a home that the potential downward price discovery of existing homes is large enough to find a buyer in all but the most extreme circumstances."

.....?