The End of Location, location, location

Broken real estate supply has changed the rules for real estate analysis

I saw a thread from Jay Parsons, a housing economist, on Twitter, that I thought might work as a backdrop for a post about how real estate has fundamentally changed.

Two tweets from the thread were especially interesting.

https://twitter.com/jayparsons/status/1665832536302288896

https://twitter.com/jayparsons/status/1665832540555321346

I will generally support his first point and push back against his second point. And, since he introduced Dallas, I will reference Dallas. I am using prices in this analysis because there is more data over a longer period, but, rents follow generally the same directional patterns.

The Coming Supply Glut?

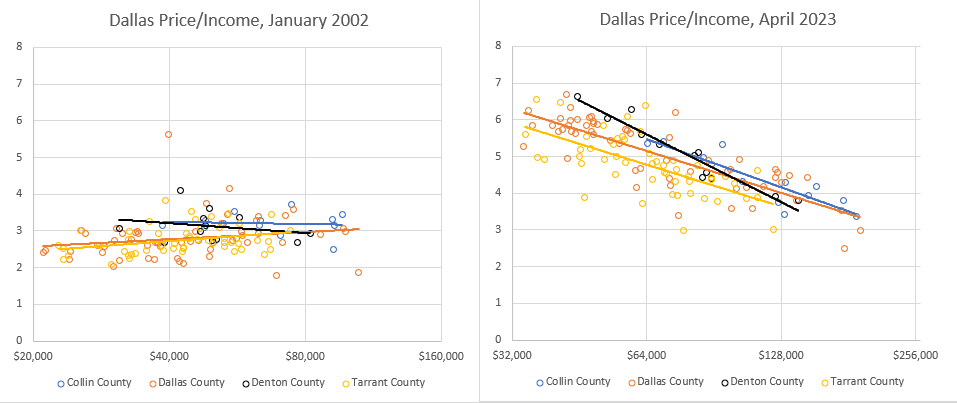

Figure 1 shows price/income ratios in ZIP codes across the Dallas-Fort Worth metro area, arranged by ZIP code average reported incomes. The pattern was roughly similar in 2012 as it had been in 2002. Then, as my research has highlighted, prices shot up in a systematic income-sensitive pattern. This has happened for a long time in some cities that have had low housing production. In the past decade, every city has had low housing production, and so this has happened in every city.

So, the people Parsons is referencing in his first tweet have been warning of a supply glut during a decade that, unequivocally and to an extreme degree, has developed the worst supply shortage since records have been kept. That position isn’t even wrong. It’s ridiculous. One reason it is so enticing, in spite of being ridiculous, is that in a context without the land use and lending constraints the US market has developed, low interest rates could conceivably trigger added supply. And, conceivably, since that supply would have been somewhat induced by low rates, it would be vulnerable to some market reversal if rates increased.

In any context with ample supply, it really would be extraordinary for prices to rise much higher than normal, and it would be reasonable to associate some of those rising prices with low interest rates, if interest rates were low. Prudent analysts and market participants would be smart to prepare for a reversal. But it’s the wrong context today. And so analysis that would otherwise be prudent is increasingly mistaken. It’s tough to make a regime change from a sincerely prudent position when everything in your background of hard-won experience tells you you’re right, but the world has changed (and, by the way, one way that you have maintained a disciplined, wise approach to analysis has been to ignore previous claims about the world having changed).

Figure 2 gives some indication of why some market analysts would be wary of new supply. The blue line is the number of building permits issued in Dallas per thousand workers (a ratio meant to compare relative rates of new building over time). Construction in Dallas has been recovering for more than a decade, and is back to near the levels of the late 1900s and early 2000s. The red lines are vacancy rates for rented (solid line) and owned (dashed line) homes in Texas. Vacancies have been on a downward slope since the early 2000s.

Just doing some basic chart reading, it looks like Dallas markets are in a similar supply and demand context as they had been in the mid-1990s. Rental vacancies are around 8% and housing production is above 15 units per thousand workers. Vacancies among owned homes are still very low, though.

Figure 3 shows Dallas home price and rent trends compared to general inflation (here, using CPI prices excluding the shelter component). As Figure 3 shows, for several years in the late 1990s, rents (red) and prices (blue) continued to rise moderately in Dallas. It wasn’t until rental vacancies rose above 12% that rents and prices started to moderate. This suggests that Dallas has several years of building to accomplish before it has much of an effect on prices and rents.

The recent divergence between rents and prices in Figure 3 is due to the nature of recent inflation. Such price spikes can’t be picked up by CPI surveys immediately, so there has been a lag in reported rent inflation in the CPI measure, but as Figure 4 shows, with Zillow market estimates, recent spikes in rents and prices have been roughly parallel with each other. Some of this is due to the spike in general price inflation, some of it due to Covid-related housing demand, and some of it a continuation of the decade-long lack of adequate construction.

As Figure 1 makes clear, Dallas isn’t entirely in a similar situation as the mid-1990s. There is a lot of accumulated rent and price inflation at the low end of the market because of the accumulation of supply deprivation. On the one hand, this means that ample supply could (and should!) bring down the real rents and prices of low tier homes in Dallas much more sharply than it would have had the capacity to in any previous market context.

On the other hand, these excessively high costs are due to inertia of families attempting to stay in their existing homes. The costs are driven higher by demand coming from potential new tenants compromising down-market to deal with rising costs, which has to rise high enough to induce existing families to either reduce their housing consumption or leave the city entirely. In a city like Dallas, where domestic migration has generally been positive, on net, this means a slow-down on in-migration more than a rise in out-migration. But, in either case, the moderation of this process will be measured if supply can increase. The reason those rents have been driven higher is that households that should be moving into better units have been compromising down-market to economize on nominal expenses. They represent a lot of pent up demand that will naturally fill in new supply as it is approved. As low tier prices and rents moderate, families with low incomes will either stop migrating away or increase migration into Dallas. All told, it took a decade for these costs to accumulate, and it would be hard for them to recede much more quickly than they appeared.

This is one thing that really throws off the analysts that are still focused on interest rates. Interest rates can sometimes change quickly, as they have since 2021, and so if they were particularly important, then possibly, sometimes, a large enough change, fast enough, could lead to a sharp reversal in rents and prices. It is likely that they were responsible for rent and price appreciation declining as quickly as it has over the past year. But, that is just some marginal noise around the more important factors in the new housing context that will only serve to keep traditional analysis in a state of confusion.

The End of Location, Location, Location

That brings us to Parsons’ invocation of some other real estate wisdom from a context we don’t have any more - that market supply isn't the story, supply on one side of Dallas doesn't matter to other side, and that real estate is local. In the parlance of traditional real estate analysis, real estate is all about “location, location, location”.

In Figure 5, I have broken out ZIP code Price/Income levels in Dallas by county. The first point I would make is that, absolutely, supply on one side of Dallas matters to the other side. There is little difference in the systematic trends in price between the various counties in the Dallas metro. These trends are overwhelmingly driven by 2 factors - neighborhood incomes and metropolitan area supply.

This is similar to the issue with interest rates. It’s not so much that location doesn’t matter at all. It’s that it has become overwhelmed by the systematic consequences of inadequate supply.

It’s like, if you’ve been training for the hundred yard dash, and you work on getting off the blocks fast, long strides, the speed of pumping your arms and legs. Diligently working on all of those things could cut a half second off your time, and that half-second made a huge difference in your success.

Now, the rules committee says, from now on, there will be defense. The other runners can obstruct you, trip you, get in your way, etc. Now, there are more important things to worry about. It doesn’t mean that those other skills are completely unimportant. It doesn’t mean they couldn’t still help you cut a half-second off your time. It just means that they are practically irrelevant, now, to whether you win the race.

Things like location and interest rates used to be important because they used to exist in a context where small factors (at the micro-level, with location, and the macro-level, with interest rates) were determinative because they existed in a vacuum. By that, I mean, they existed in a context where those price/income lines in Dallas were persistently flat, at around 3x incomes, plus or minus a fraction of a point. In that context, if you are trying to “win” the real estate “race”, the main source of differentiation is which of those dots you pick on the scatterplot, and the idiosyncratic movement of that dot compared to the other dots.

In statistical terms, in Figure 1, the r-squared of the lines in 2002 and 2012 was negligible. Systematic things happening with aggregate Dallas metro supply and demand didn’t matter much. Everything was about idiosyncratic differences - location, location, location. In 2023, the r-squared is 0.59. Idiosyncrasies now matter less than the systematic game of “musical chairs” that forces higher costs onto families with fewer resources.

It’s a regime shift. This time really is different.

Figure 6 compares incomes and home prices across Dallas in 2002 and 2023. The green arrows describe the local adjustments that must be made when housing is unduly scarce. Rich residents spend slightly less for a less valuable existing home, though it is more than its previous residents would or could have spent. The poorest residents have compromised away all the amenities they can manage to, so that they either pay more to retain what they have or they move away entirely. And, every family in between exists on a scale between those two extremes.

One thing that may make it difficult to see these new changes is that they aren’t obvious on a normal scale. Just eye-balling that chart, it just looks like Dallas, in general, has gotten more expensive since 2002.

Both incomes and home prices operate in terms of rates of change, which is more appropriately viewed on a log scale. On a log scale, like in Figure 7, the cantilever transition of housing costs is clear. This happens in every supply constrained city. Viewed exponentially, if trends of the previous 20 years continue in Dallas for another 20 years, the average home price in every ZIP code across the city will cost more than half a million dollars. Of course that is absurd. The fact that such an absurdity would result from a reasonably short continuation of present trends should alarm you.

In Figure 6, the green lines represented the trends of residents. In Figure 7, think of the green lines as the trends of homes (here, aggregated into ZIP codes). Where families with fewer options are holding on to the existing stock, the ZIP code price increases - the dot moves up. Where families are moving down-market into lower priced homes in order to economize, local incomes in the destination ZIP code increase and prices rise - the dot moves right, and up a bit.

In a way, this makes location more important. Before, the question of location quality in different parts of the metro areas probably were relatively unrelated to each other, as Parsons suggests. Now, to the extent that location is still important, it is increasingly a question of where each neighborhood fits into these aggregate metropolitan area wide substitutions.

A scatterplot between the current income level of each ZIP code and the change in each ZIP code’s typical price/income since 2002 highlights the dominance of these trends. Price/income levels were relatively similar across Dallas in 2002. Differences between locations, such as length of commute, which may have been responsible for some of the idiosyncratic differences in price/income, tend to be stable over time, so tracking the change in price/income levels over time, as in Figure 8, highlights these systematic factors. Current income in each ZIP code accounts for 74% of the change in price/income ratios since 2002. The stresses of economizing on housing dominate home price trends in Dallas. It doesn’t matter if you’re in Arlington or Fort Worth. You’re all on the same roller coaster.

The strength of the correlation is the result of two types of changes.

Prices rising for families with low incomes who pay to avoid being displaced - “costing more”

Prices rising moderately as neighborhoods gentrify when richer families move in to the existing stock of homes when there aren’t enough new homes in the high tier neighborhoods to accommodate their demand. The result is that the average income of the gentrifying neighborhood rises, the average home price rises, but the price/income level moderates.

In summary, real estate has always been about location, location, location, but now it’s about incomes, incomes (as it relates to the migration of families into existing neighborhoods in search of scarce housing), location.