I have had the opinion that the Fed would need to break a lot of things before it could break the housing market. But, I think there is a chance that the Fed doesn’t really break much at all.

There is a lot of bold pessimism out there, especially among housing pundits. I don’t envy them. If your job is to have your finger on the pulse of the marketplace, and one of your competitive advantages is anecdotal insider perceptions, then you just can’t risk being blasé about a potential downshift in market trends. Unfortunately, I think this greatly hampers the value of that insider access, because the pundits themselves become very procyclical. In a way, it’s their job. But, it’s tough to do that job without overwhelming the natural ebbs and flows of the market with the ebbs and flows of the cherries you’re picking.

There is also the issue of the unfortunate model that the Fed communicates with, which leaves a plurality of investors and pundits with the notion that interest rates are a policy choice with a causal path that goes from rates to spending and investing decisions. Low real rates purportedly mean the Fed is creating arbitrary false stimulus and high rates mean that stimulus has been removed. So, there are a lot of folks that have been waiting for a downturn for a decade, and I just think the median observer has a biased frame of mind from that.

Also, the Fed communication model lends itself to an overdeveloped sense of pessimism when natural interest rates are low. Either rates are too low, which means that the economy and asset markets are overstimulated and inflation is just around the corner, or rates are high. And, the only reason rates in this context could be high is because of high inflation, and so high rates seem to confirm the pessimists’ fatalism. When a growing economy with moderate inflation would be associated with low interest rates, there is no point in the business cycle and no general outcome which would lead a plurality of observers to say, “Oh. This is good. It looks like everything is moving along just fine.”

So, when that is the case, if you observe that things are just fine, you’re bound to be a contrarian. My concern is to try to make sure my contrarianism is selective and objective. It is possible that the Fed has been or will be unnecessarily pro-cyclical or that new home construction is about to enter a deep contraction, and those things could happen even if my criticisms of the pessimists are accurate. In fact, the pessimists caused the 2008 crisis. (Read about it here!) So, the pessimism could be important, even if misguided. But, I think the base case is still positive.

First, let’s look at GDP growth and inflation. In Figure 1, I show quarterly % changes in nominal GDP, real GDP, GDP inflation, and 3 CPI inflation indicators (total, core, and excluding shelter).

Nominal GDP growth was higher for longer than anticipated in 2021, but the glidepath back to 4-5% is 3 quarters old now. And while the Ukraine war likely added an inflation bump as we entered that glidepath, it is also now decreasing. This is clear in the GDP deflator (and as I pointed out previously, is a primary component of declining nominal residential investment).

How can you look at those trends and not be optimistic? If I had asked you to project a rosy scenario 3 quarters ago, given the Ukraine war, wouldn’t your chart have basically looked like this?

Furthermore, much of the recent consumer inflation was in volatile food and energy components. And, while core consumer inflation was a bit higher than total consumer inflation last quarter, that was basically because of rents. So, as the last bar shows, excluding rents, we have now had a full quarter of deflation. The CPI shelter price component tends to lag market rent trends, and much of it is related to the rental value of owner-occupied homes, which is really not particularly tied to cyclical monetary trends. Powell has indicated that he understands this, though he has to maintain a public anti-inflation posture while he acknowledges it.

The Atlanta Fed’s real-time GDP forecast measure is bullish for the 4th quarter, currently projecting about 3.6% real annualized GDP growth. Given downward inflation trends, which at this point appear to be pretty broad among components that had been high - lumber, shipping, used cars, etc. - a 3.6% real growth with sub-2% inflation, seems likely. Given the backward looking bias of cyclical sentiments, this must sound radically optimistic, but this is simply the base case trend.

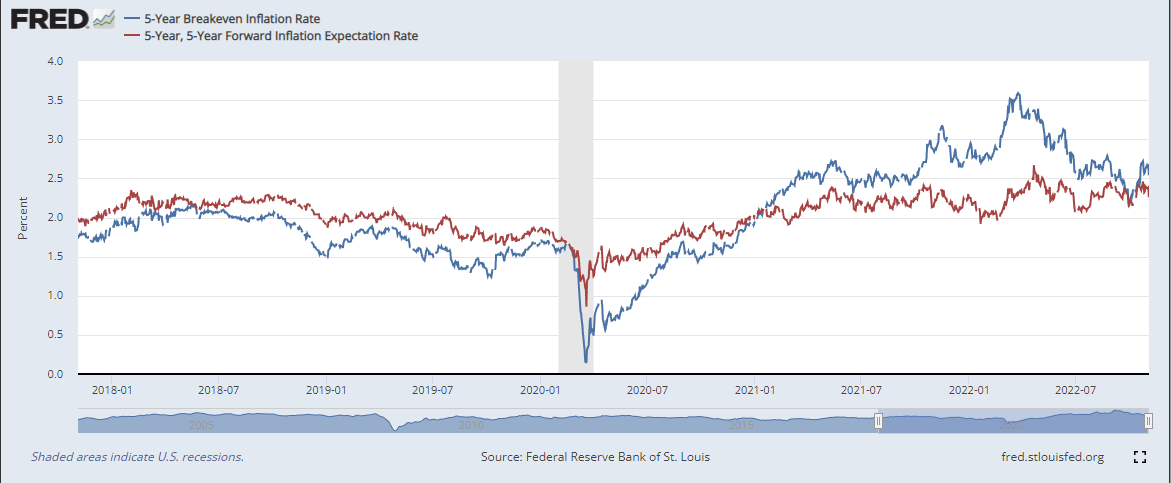

Powell is appropriately appeasing the press by genuflecting to trailing inflation, but is there any reason to expect a reversal back to high inflation? A month is noise. A quarter is a trend. A year is the monetary policy position. How many months or quarters of disinflation, or outright deflation, will need to add up before sentiment is nudged from a backward bias to a forward bias? 5-year inflation expectations peaked at the end of the first quarter. There is no market expectation of unusual inflation going forward.

There will be two CPI reports before the next Fed meeting - the November report is scheduled for that very morning, December 13. Currently, Powell is talking about slowly coming to a pause in rate hikes, sometime in early 2023. Futures markets reflect a rate hike peaking in March 2023 at 5.25% and staying there for a bit.

But, I ask you, if at the December meeting, we have 5 full months of deflation in non-rent CPI, will sentiment still be lined up against defeating inflation from last March? At some point, the sentiment will have to flip, and I still have hope that Powell will be ready to flip with it. Both currency and deposits have levelled off for some time, and I think for the Fed to target short-term rates above 5% next summer, they would have to engage in the same disastrous types of monetary contraction that they did back in 2008. I don’t think the public or Powell have the motivation to do that, even if there will inevitably be a contingent of bubble-mongers who think the nominal economy is built on a house of cards and will never be convinced otherwise nor satisfied with anything but nominal contraction, unemployment, etc.

Figure 5 shows the evolving yield curve - Eurodollar futures contracts at several points in time, with October 2018 as an added reference. (Subtract the contract price from 100 to get the expected forward 3 month lending rate at any point in time.)

I think there are several different impulses driving changes in the yield curve. Temporary inflation and the Fed’s policy response to it have made the short end especially volatile. This has created a steep inversion, but I think for the most part, the particular shape of the short end of the curve isn’t that important right now. At the long end, future rates have risen from just over 2% in February to about 4% today. That is bullish, and I think it is reasonable to infer that the bullishness reflects the success of Jerome Powell to let short term inflation and inflation expectations rise without creating an unnecessary contraction. We will be better off in the future because Powell and the FOMC didn’t listen to the pessimism that their own poor communications model sows.

What I would like to see, come next March, and I admit this is unrealistic, is the short end of the curve back down to, say, 3%, while the long end remains at 4% or greater. The economy, and the housing market, will be a lot stronger in that scenario than they would be in a scenario where the long end of the yield curve is eventually back down to 2-3% and 30-year mortgage rates are back to 5% or less. That seems undeniably true, and it is one of many reasons for bucking the analyst norm of treating mortgage rates as an important linear causal factor in housing market activity. (That’s not to say that if you look hard enough and selectively enough, you won’t find some! Some of it is even important.)

I think I’ll leave it at that for this post, and I plan to have a post up later for subscribers that digs a bit more into the optimistic case for homebuilders.

In summary, contra-Larry Summers, etc., if inflation recedes without being paired with recessionary conditions, we should definitely not look a gift horse in the mouth, and we should thank Jerome Powell and the Fed. And, if that happens, maybe, just maybe, the positive effects of such good nominal economic management will leave long term interest rates higher as a result, and the temptation to misconstrue low rates as overstimulation will be neutered a bit.

I agree with you on this, particularly when it comes to seeing where more chips fall come March 2023. My crystal ball tells me that there will be some more churn over the winter that manifests as post-Holiday slowdown and a stabilization of interest rates. Spring will bring some downward pressure on mortgage rates as inventory builds up, but builders should react with more starts in a more stable environment. And, if California keeps on strangling zoning codes, they could see a population uptick again coinciding with more multifamily starts and completions. (That may take a few years to bear real fruit, given standard construction timelines)

Conversely, April could turn out to be the cruelest month---with a Government shutdown, persistent inflation, higher unemployment from a burst tech bubble, and a vigorous trade war with China that continues to cause havoc to supply chains.