Here, I’m going to take another stab at back-of-the-envelope estimates for the cumulative shortage of residential investment and the effects that correcting it would have. Playing with the numbers in a slightly different way than before, just to keep doing a reality check.

Housing Expansion - 1940s to 1970s

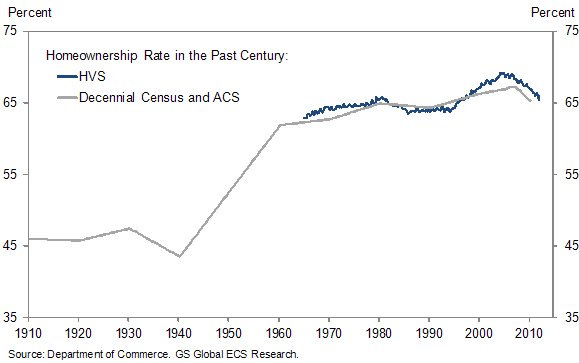

After the Great Depression and World War II, the United States famously created a massive boom in homeownership. Before 1940, homeownership had trended around 45%. By 1960s, it was up to the 60%+ range where it has remained. Within age groups the homeownership rate has remained relatively flat since then. Most of the rise before 2004 was due to age demographics. (Homeownership rates are higher among older households.) Since 2008, the demographic rise was countered by a return to age-group homeownership rates back below the late-20th century norm.

The rise in homeownership after 1940 was mostly facilitated by the reduction of financial frictions. Federal agencies that facilitate mortgage access and the maturity of modern financial markets made ownership more accessible.

I write frequently about how the recission of that access after 2008 has made housing more scarce and expensive. That seems counterintuitive. But, it shouldn’t be. This should already be the universal expectation from the experience of the post-WW II boom.

Figure 2 shows the rise in real value (left panel) and inflation (right panel) for housing rents (blue) compared to total consumption (red), from 1929 to 1977. During the period with sharply rising homeownership and expanding mortgage access, real housing outpaced other consumption and rent inflation was low.

In other words, when financial frictions were reduced so that demand for homeownership increased, we built a lot of homes and we paid less for the privilege of living in them.

Mortgage access lowers housing costs.

This comment from an AEI Housing Market report about the current market reflects the canonical point of view on this, I think. By that, I mean that AEI considers the logic of the assertion that credit access raises prices to be axiomatic. An explanation is unnecessary. “In the low and low-medium price tiers, FHA accounts for over a quarter share in each, while together FHA and the GSEs have a combined share of around 70%. The battle for market share between FHA and the GSEs is therefore largely taking place in these price tiers. An unfortunate consequence of this taxpayer backed battle is upward pressure on constant quality house price appreciation.”

Decades of 20th century experience suggest, quite strongly, otherwise. Massive increases in homeownership were associated with higher residential investment. That lowered rents and prices.

One could argue that current conditions are supply constrained, and so demand from credit access has a more inflationary effect than it used to. But, before we get into current conditions, let’s look at price trends before the 1980s.

As shown in Figure 3, price/rent ratios (red) declined during the expansion period. Accessible mortgages didn’t even increase the market price of ownership relative to tenancy. And price/income (blue) was also moderate. Here, this is the total value of owner-occupied real estate over the total income of all households. So, when ownership was increasing in the 1950s, the price/income figure I use here rose as a result of having more homeowners. Then, it levelled out, and even retreated a bit in the 1970s.

One thing I want to emphasize here is that these are not subtle trends. The increase in homeownership from 1940 to 1960 was dramatic - nearly 20% of households. If it is not a definitive empirical confirmation that credit access lowers housing costs, it certainly should at least create a strong benefit of the doubt contrary to AEI’s axiom.

Housing Supply Constraints - 1980s to 2000s

After 1960, homeownership leveled out, and for a while both the real growth and price trends of housing generally followed broader trends in real growth and price inflation. In Figure 4, I have indexed both to 1977. You can see that rent inflation became excessive by the mid-1980s, and was followed by a decline in real housing growth.

Americans were getting less house and paying more for it, but mostly were paying more. By the Great Recession, real housing consumption was about 15% below broader real consumption growth, but rent inflation was about 30% above it.

This is because supply constraints were regional. So, eventually, housing was constructed somewhere, but it required regional displacement of families out of the constrained regions. Rents increased in the constrained regions until some families chose to move to less constrained areas. When they were attempting to remain in the supply constrained regions, they cut back on housing to try to maintain affordability. But, when they moved to the less constrained regions, they consumed housing the way families do in less constrained conditions.

The combination of those factors added up to more rent inflation and some decline in real housing growth. And, those trends were very different in the supply constrained cities than they were in the less constrained regions.

This period was associated with rising price/rent ratios (looking back at Figure 3). Was this a joint product of constrained supply and expanded credit access, or was it really mostly the former?

It was mostly the lack of supply.

First, looking back at Figure 1, the rise in homeownership in the 2000s was very much smaller than the mid-20th century rise.

Second, demographics has created a natural upward slope in homeownership. Age-adjusted homeownership had declined after 1980, bottomed out in the mid-1990s, and rose back up until the mid-2000s. At its peak, the homeownership rates in 2004 were generally no higher within age groups than they had been in 1980.

All that being said, there was certainly an increase in homeownership from the mid-1990s lows until the mid-2000s. However, that rise was not very well correlated with rising prices. In fact, as you can see in Figure 2-2, from “Shut Out”, fully half the increase in homeownership happened with no increase in real home prices at all. And half of the remaining increase in homeownership happened before 2002, when the price/rent ratio was still below the mid-20th century peaks.

And, at the back end, 1/3 of the price appreciation happened after homeownership had peaked.

Now, certainly, credit access wasn’t constrained during this time. How much of the rise in prices should be attributed to credit access and how much should be attributed to constrained supply? That is a frequent subject of this substack. Here, I think we can leave it unanswered because the post-2008 period gives such a strong affirmation of the supply explanation. And most of the drop in aggregate supply happened after the peak in homeownership.

Credit Collapse - 2008 to Today

In 2008, credit access was deeply cut back. Looking again at Figure 4, From 2008 to 2023, excess rent inflation accumulated to about 16% and real housing consumption retreated by 18% compared to other consumption. That amounts to more than 1% annually for both.

This is the mirror image of the 1940s to 1970s period. And, this is the period where the blunt shortage of residential investment has mostly developed. Before 2008, most of the supply constraint played out as regional substitution. Homes that couldn’t be built in one city were built in another instead.

But, since 2008, there has been a suffocating national deprivation of units that really do simply add up to a shortage.

How much residential investment do we need?

Figure 6, from a previous post, gives an estimation, over time, of the rent that pays for structures (real housing) and the rent that has been inflationary. By 2023, about 38% of aggregate rental expenditures were accumulated inflation.

The average rent is $2,107. But, only about $1,285 is for real housing. The rest is excess rent inflation. The trends in Figure 4 and in the base rent in Figure 6 suggest that real investment into housing would need to increase by about 32% to get back to the mid-20th century level of real consumption. That would amount to an average rent of about $1,700. But, I contend, that extra housing would also reverse the cumulative rent inflation.

With enough residential investment, the average American would live in a home with a rental value of $1,700, and they would actually get a $1,700 home for it. Today, the average American lives in a home worth $1,285, but they must pay $2,107 for it. The owner pockets the difference as economic rents. (Of course, for owner-occupiers, the owner is the tenant.)

I have previously estimated the typical price/rent ratio of structures to be about 12x. A home that costs $240,000 to build can fetch rent of $20,000/year where land rents are minimal.

Gross rental value of American housing today is $2,643 billion annually. Only 61% is for structures (the base rent portion of Figure 6). Americans will increase their stock of structures by 32% if supply conditions allow it. (This is the amount of growth in real housing to get back to 1970s levels relative to incomes.)

There are 3 avenues where supply could come online:

single-family build-to-rent (this will occur under current conditions)

More infill multi-family development (this will accumulate slowly with YIMBY political momentum)

Rising homeownership (this could fairly easily be allowed with better underwriting at the federal agencies but it is currently a non-starter)

And, finally, each $1 increase in the annual rental value of homes will require about $12 of residential investment.

So, the back of the envelope estimate of pent up demand for residential investment is:

2.643 (current total rental value) x 0.61 (portion of rent that pays for structures) x 0.32 (growth in structures to get back to mid-20th century norms) * 12 (construction cost of $1 of rental value) = $6.2 trillion (residential investment to get back to a normal housing supply).

Residential investment in 2023 was $1.074 trillion.

In 2023, the average new home cost $359,000. At 359,000 each, $6.2 trillion is the equivalent to 17.3 million additional homes.

I think if these things could happen, the additional homes might tend to be smaller than the average home constructed in 2023. Maybe in a fully unobstructed market, this would amount to more like 20 million homes that averaged $300,000 each. Or, maybe existing homes would be renovated. Or maybe many of the new homes would replace existing homes, so that the rate of tear downs increases and the total net number of new homes would be less than 17 million.

Those are all marginal details.

On an issue this big, the back of the envelope tells us most of what we need to know. And, again, I conclude that all signs point to something close to 20 million units. The marketplace, where it legally exists, will clamor to provide them. Your neighbors will clamor to stop the marketplace from functioning.

I like your mathematical exercise at the end of this post because it corresponds nicely to various figures that have been tossed around on this blog and other odd corners of the internet about the overall volume of the housing shortage. I seem to recall that people who are informed about the condition of housing in the U.S. will note that we're short between 10 and 20 million dwellings. Other people will claim that we don't have a shortage at all, and point to the number of vacation homes, price declines in select regions, and the fact that there aren't 7 million unhoused people wandering about living in tents or under bridges. The "No Shortage" crowd will also point to the decline in average household size from 1940 to the present day. Perhaps the moral fiber of the nation could be restored with families packed into small dwelling units--along with some kinder, kirche, and kuche thrown into the mix. Alas, I digress....stay focused!

The math behind the price trends, and the objective conditions of rent stress that persists in many metro areas, tells the truth. I would also like to emphasize that there is a qualitative aspect to the problem which plays out in nearly every real estate transaction across the country except in places that are experiencing true population loss. These include:

-Bidding wars for used houses in popular neighborhoods

-Construction resources directed at constant renovations of houses and buildings that should really be demolished (Disclosure: I make money as an architect on this either way)

-The persistent belief that housing is a perpetually appreciating asset class regardless of its physical condition

-The frustration experienced by younger generations when they try to start a family and realize that they're getting shafted by policies put into place by prior generations

The road out of the housing shortage is when the frustrated people constitute a majority voting bloc at various levels of our democratic system. I hope some of them are reading your stuff.

Really glad I found this substack, more people should know about it! I'd be interested to know your take on https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2024/8/19/the-housing-market-is-a-bubble-full-of-fraud-and-its-going-to-pop. Strong Towns seems generally pro-housing but that's a weird take if we are supply-constrained.