There is an NBER working paper by Sven Damen, Matthijs Korevaar, and Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, titled, “An Alpha in Affordable Housing?” (hat tip: Scott Sumner)

Here is the abstract:

Residential properties with the lowest rent levels provide the highest investment returns to their owners. Using detailed rent, cost, and price data from the United States, Belgium, and The Netherlands, we show that this phenomenon holds across housing markets and time. If anything, low-rent units hedge business cycle risk. We also find no evidence for differential regulatory risk exposure. We document segmentation of investors, with large corporate landlords shying away from the low-tier segment possibly for reputational reasons. Financial constraints prevent renters from purchasing their property and medium-sized landlords from scaling up, sustaining excess risk-adjusted returns. Low-income tenants ultimately pay the price for this segmentation in the form of a high rent burden.

Yes, yes, yes, and yes.

Alpha is a term of art in finance that means excess gains after accounting for risks, etc. And, the title is all you need to know. Owners of low tier single family homes earn alpha, even after accounting for things like dealing with difficult tenants. So, imagine how lucrative home ownership is for a family who is their own tenant in a low tier house.

The authors consider the difficulty of measuring the value of homeownership for low-tier residents. They conclude: Estimates of imputed rental value of owned properties “fail to remove expense categories such as property management and vacancy and credit losses, which increase rents but are not relevant for owners. This leads to an overstatement of housing consumption that is more pronounced for low-income renters, Put differently, there is more housing consumption inequality than we measure.”

Note, especially, from the abstract, “If anything, low-rent units hedge business cycle risk.”

In 2008, we permanently legally barred something like 15-20 million households from owning that asset.

Consider how diabolical it is that in the US, in 2008, we decimated the affordable single-family housing market by legally barring many of its potential owners from buying, which cratered the for-sale market for affordable homes. Today, among American economists and finance hawks, the conventional wisdom is that 2008 proved how cyclically wild affordable housing is, and so it was right of us to decimate it in order to protect future tenants of affordable housing from the temptation to be owners.

Policymakers created a price shock, pretended they hadn’t, and then acted as if that price shock was something that required holding their thumbs permanently down on the mortgage market. But, as this paper points out, if you measure the returns of rental housing in terms of rental yield on the original purchase price, low-tier rental housing performed well, and regularly performs well.

Families look to economize during recessions. So, when the economy contracts, new construction (which is mostly high-end) declines, and demand for older, existing homes increases. Rents on those affordable units are less cyclical because of this.

Interestingly, the authors also look at regulatory risks. For instance, landlords might require higher returns in states with potentially onerous tenant protection laws. But, they found little difference between high regulatory states and low regulatory states. Returns on low-tier landlordship were high in both. My interpretation of this is that tenant protections (depending on how they are implemented) might increase landlord cost, but they don’t lead landlords to demand higher net yields after accounting for those costs.

Among their conclusions:

What are the implications for housing affordability? Our analysis points in the direction of policies that work to alleviate the frictions preventing arbitrage. One set of policies could focus on stimulating the flow of institutional-quality capital towards the lower tiers of the rental market….make it easier for renters in the low-rent segment to purchase their own home….Those policies are likely to be more effective when supply is more elastic.

Finally, adding supply in the low-rent tier of the market would also lower returns. One issue here is that new construction is almost by definition rather expensive. In the US, large federal, state, and local subsidies are paramount for the private development of affordable housing. Adding supply in higher-rent market segments may also help since it may trickle down to the low-rent tier through moving chains.

If you’re blocking new housing because it’s not affordable, market rate, owned by large corporations, etc., you are not helping. If you’re blocking access to mortgages because you’re afraid that they make housing less affordable, you are not helping.

There is a certain amount of bipartisan support for not helping, and that is why we have a crisis. Kudos to these authors for putting in a lot of background work to add sanity to the academy.

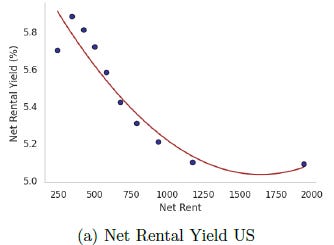

Here’s one chart from the paper, quantifying the different net rental yields they measure in the US. Units with higher rental value, even after expenses, sell for higher prices. Price/Gross Rent is higher when gross rent is higher. And, even Price/Net Rent is higher when net rent is higher.

Among the papers cited in this paper, there are some others that have also made similar conclusions: Homeownership is especially profitable for families that live in affordable housing.

“The Cross-Section of Housing Returns” by Halket, Loewenstein, and Willen.

We document large systematic variations in the return to single-family residential property within U.S. metropolitan areas. Areas with low income, low credit scores or high shares of black residents have higher yields and therefore higher returns. Yield spreads between low credit areas and high credit areas widened considerably during periods when credit availability was low.

“Total Returns to Single Family Rentals” by Demers and Eisfeldt.

We believe that we provide the first systematic analysis of total returns to Single Family Rentals over a long time period, in a broad and granular cross section…. Within cities, we show that lower-price-tier zip codes have higher total returns as a result of both higher yields and higher house price appreciation.

Here’s a recent post of mine, discussing higher yields on low-tier homes.

Thanks for this. I am on the board of our local Habitat for Humanity, and our goal is to get people into affordable homes as homeowners. The problem we are having right now is that the costs to build and the resulting insurance are so high that even with volunteer help and discounted contractors, the homes are still out of reach for many in our target groups.

Part of the problem is ours - our donors and board members are typically upper-middle class, and they're used to a quality and size of home that doesn't make sense for our target group, but the pressure and bias is there to increase costs.

We are actively looking at modular construction as an alternative to both lower costs and remove the temptation to add more bells and whistles that do nothing but make the homes too expensive.

Great interview on Odd Lots by the way.

“ Consider how diabolical it is that in the US, in 2008, we decimated the affordable single-family housing market by legally barring many of its potential owners from buying”. What was the legal bar to buying?