Homeownership isn't that risky

Purposefully wiping out much of the value of low-priced homes from 2008 to 2012 had obvious primary consequences but also some subtle secondary consequences.

Frequently the same people that defend and approve of the mortgage crackdown will also focus on how risky homeownership is. This idea is deeply embedded in all of the mistaken conventional wisdom about the period.

Is there any idea about the 2000s boom more popular than “Naive people thought home prices never go down.”?

It is a key fundamental underlining the moral panic. People needed to learn. We showed them, didn’t we?

Of course, prices on homes in neighborhoods that weren’t affected by the mortgage crackdown didn’t really go down much.

It’s sort of like tying concrete blocks to someone’s ankles, and then scoffing, “The dummy should have taken swim lessons.”

I reject the point on several grounds:

There isn’t great evidence that this idea suddenly reared its head in a broad way that affected national home price trends in any significant way. Anecdotes aren’t data. And, as I constantly point out, much of the country didn’t experience either a building boom or a price spike, yet the mortgage crackdown caused prices in low-tier neighborhoods to collapse everywhere.

To establish that this sentiment was important, you’ll need to correct for the mortgage crackdown, because there is no reason to apply this idea to markets where new home construction was moderate and price/income levels had been flat for years before suddenly dropping by half in many places.Home prices across the nation really don’t go down collectively, and homebuyers in most places shouldn’t have had to expect them to. To the extent that people believed home prices wouldn’t go down, they were basically correct, or at least should have been or would have been if we hadn’t become so sadistic.

The trend-following speculators that showed up late in the cycle are (1) not a good example of this and (2) were, more often than not, stabilizing prices where they were active in 2006 and 2007 rather than driving prices up.

Actual owner-occupiers are generally very non-speculative. They want to enjoy the benefits of ownership and they generally are wary of the risks. The idea that housing is characterized by bouts of irrational exuberance is, really, mostly a product of Robert Shiller not understanding why housing is expensive.

Here is the nominal Case-Shiller index, and the Case-Shiller index, adjusted with the Erdmann Housing Tracker Credit Component. If you accept the scale of the tracker estimates, essentially all the net loss of real estate in nominal terms was due to the mortgage crackdown.

Keep in mind that this is a national average. During that time there was a lot of variation. Without the mortgage crackdown, home prices in Phoenix might have still averaged nearly a 50% loss from 2005 to 2010. But, Dallas might have been up around 30%.

So, it is definitely the case that in some unusual situations, home prices can go down enough to matter, locally. Phoenix in 2005 was definitely one of them. And, several cities experienced some losses in 2022. For that reason, and because of high transaction costs, it isn’t usually a great idea to buy a home you don’t intend to live in for at least several years.

But, actually, as with so many of the myths about the pre-2008 period, the price trends don’t really confirm the claims. Did buyers in Phoenix in the 2000s suddenly decide that home prices never go down, but buyers in Dallas remained more risk averse? Was that the difference between Phoenix and Dallas? Was it the difference between Phoenix in 2021, 2015, or 2005? Or Dallas?

Obviously not.

It’s a standard “behavioral finance” explanation that allows researchers to be incurious about what actually moves markets.

But, the biggest problem with the Case-Shiller charts is they are just measuring capital gains.

First, if you rent a home, do you think it will be a good investment for the landlord? It is much easier to be a landlord to yourself than to someone else, so if it would be a good investment for the landlord, then surely it would be a good investment for you. And, this is clear because landlords rarely are willing to outbid homeowners in markets where homeowners have access to capital.

One of the knocks against homeownership is that it isn’t diversified. A large portion of your net worth is tied up in a single asset that might lose value at the same time that local labor markets sour and you get laid off.

Some studies have shown that homeowners are less flexible in those cases. I have lost track of it, but a long time ago I saw an interesting paper on that issue. They found that homeowners with mortgages behaved similarly to renters during employment downturns. It was free-and-clear owners who behaved differently. The implication was that homeowners were less reactive to local labor conditions because those who had paid down their mortgages didn’t have a big rent check to keep up with, or maybe even had access to home equity. They were inflexible about labor or migration decisions because they had more choices and fewer obligations.

And, anyway, most landlords are not diversified either. Most single-family rentals have traditionally been owned by small investors with just a few units in the same market.

What I’m getting at is that the risk of homeownership has been commonly overstated. And frequently the returns to homeownership are understated by not factoring in the rental value they provide.

All of this feeds into the moral panic, where we told ourselves we were just protecting those irrational home buyers from themselves. By overstating the risks and understating the returns to homeownership, everyone could believe that no harm was done by excluding others from ownership. They really shouldn’t even be taking such risks anyway!

And, then when we knocked 50% off their home values, it only proved how prudent we were being to exclude them.

Zillow has rent and price data from 2015 on. It would be interesting to look at these outcomes further into the past. But, hopefully even recent data can add some clarity here.

Obviously, there are some very local price deviations, but I think looking at the ZIP code level captures most of the potential variation in home prices.

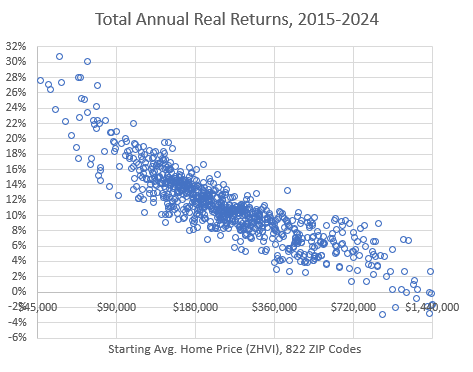

Figure 2 shows total annual real returns (after inflation) for 822 ZIP codes from 2015 to 2024. This includes both capital gains and rent. (These are gross returns. Depending on local insurance and tax rates, costs might average around 2% annually, but can vary quite a bit, so I have not included that here.)

Since 2015, returns have been highly negatively correlated with home prices (and, thus, with the incomes of their owners or tenants). Regional diversification is a very distant secondary factor. This has been the case because the main source of capital gains has been the grinding, regressively rising rents that have come from the national depression in home construction.

Figure 3 shows just the capital gains portion. Low tier homes have outgained high tier homes by 4% or more, annually.

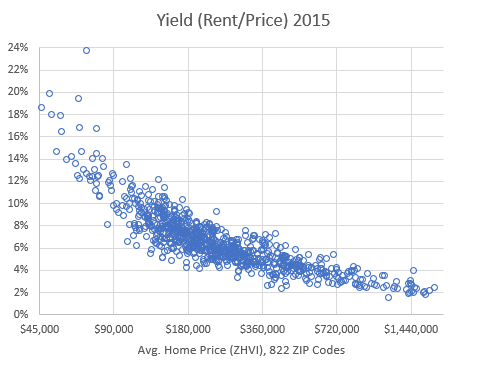

But, the more systematic advantage to low tier homes, as investments, is in the rent. Since prices were suppressed in 2015, yields on low tier homes were very high. Part of the gains since then have come from the normalization of yields.

In 2024, most of the deals have been bid away, but low-tier homes still have much higher rental yields than high tier homes. Even without capital gains, low tier homes have a 3-4% annual advantage. And, this is guaranteed. The rental value isn’t going to suddenly drop by 50%. Today, low tier homes have a gross yield of more than 6% before any capital gains are factored in.

I think part of the anti-mortgage case is the fear that buyers will overbuy because they think the home will appreciate in value. There is always a distribution of behaviors, and so there are buyers that might behave in such ways to some extent. But, the way the mortgage crackdown worked, we are systematically excluding homebuyers for whom homeownership offers the highest returns.

The rental yield is such a large part of the total value of a home, capital gains aren’t necessary to make it a decent investment - especially for most of the would-be buyers that can’t get mortgages any more.

In summary, homeownership isn’t riskless. Phoenix in 2005, for instance, was not an ideal entry point. However:

The diversification risk of homeownership is often overstated.

Housing is systematically a better investment for families with lower incomes in less expensive units, even in normal times, in all cities. Mortgage bears would have you believe that expanding mortgage access tempts buyers into reckless decisions, but it actually systematically encourages more high yield ownership.

The apparent risk of universal deep losses was a one-time event which was a public choice and cannot be repeated.

The apparent riskiness of homeownership in the post-2008 period has not been related to to the diversification problem. Price volatility has been associated with buyer characteristics rather than location since 2008 because it has been induced with national public policy.

Generally, for holding periods of more than a few years, housing investments will have positive real total returns.

Home prices shouldn’t always go up. They should go sideways, after adjusting for inflation. And in some odd situations they can temporarily decline. But they are still investments with dependably positive total real returns over reasonable time frames.

A lot of Americans are congenitally afraid of letting other families take risks. They will never be able to come to terms with what we have done to those families. A lot of other Americans interpret all inequitable economic outcomes, a priori, as a consequence of corporate power. And they will also never be able to learn what the problem is. And so, collectively, we are like a python desperately strangling itself. Millions of households would voluntarily accept the moderate risks and mundane but significant rewards of homeownership. That would mutually benefit them and some corporations who would voluntarily accept the moderate risks and mundane but significant rewards from building and funding their new homes. They can’t. We’re the python.

Our never-ending struggle will be to construct a political plurality that outnumbers those two ends of the political horseshoe.

>> I think part of the anti-mortgage case is the fear that buyers will overbuy because they think the home will appreciate in value.

People also overbuy because they expect future earnings increases to eventually make the mortgage more manageable.

Brookings (https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/A-Comparison-of-Renters-and-Homeowners-in-Recent-Decades-2.pdf) and the Cleveland fed (https://www.clevelandfed.org/publications/economic-commentary/2013/ec-201309-keeping-the-house-or-moving-for-a-job) posted studies on comparison of renters and homeowners. I wonder if your lost paper is one of those