How Many Homes Do We Need?

Almost all professional estimates of the housing shortage are ridiculously low. I don’t know what they do to their models to keep the numbers low, but it has to be hard to get such such low answers with quantitative models.

For starters, I estimate that a normalized housing stock would include 4 or 5 million additional vacancies without even accounting for household formation. Even someone being very stingy with their estimate of a historically normal vacancy rate would surely estimate a couple million more.

There are currently about 15 million vacant units, about the same as in 2003, even though the country’s population has grown by 17%.

Vacancies have been declining since 2010. Rent inflation pushed above core CPI inflation in 2012 when there were 18 million vacancies and has never retreated.

So, anyone estimating the shortage at less than 3 million units isn’t even accounting for simple arithmetic signals from the vacancy data.

The one estimate that breaks the mold is from Kevin Corinth and Hugo Dante, who have published their model at the IZA Institute of Labor Economics and for the Congressional Joint Economic Committee Republicans.

They use the same intuition I use, more or less. Where there is a shortage, the price of housing includes a “bribe that you pay to the land” in order to buy the house. So, if we have an estimate of the elasticity of demand (how much will the price decline for each 1% increase in supply), then we can estimate the supply level that would be required to eliminate the excess price or rent.

They estimate about 20 million units short.

Now, there are a lot of nits you can pick with their model. It involves estimating fixed demand elasticity, broad estimates of construction costs, and a host of other simplifications required to build a model like this.

One of the complaints I hear about the paper is that it doesn’t account for substitutions between locations. For instance, if more housing gets built in Los Angeles, that reduces the need for housing in Phoenix. I’m not quite sure I fully follow that complaint. If LA builds a house and a family moves there instead of to Phoenix, then there is an equal and opposite effect on demand in the two cities.

Maybe it comes down to the estimate of demand elasticity, and if the estimate doesn’t account for regional substitution, it could be off? I’m not sure if that’s the way to think about it. But, the complaint is that this bias in the model could bias the estimate of the national shortage up. In other words, just adding up the shortage from each city will overstate the national shortage.

I don’t have the graduate level statistics training to fully grasp the textbook version of the claim they are making. I think I do roughly understand it in my own way, and, in fact, below, I will walk through my own estimate of the shortage, which I think accounts for the issue in a way.

Anyway, back to vacancies, I think their model might also be biased low, because supply and demand measures consumption, not inventory. So, I think the 4-5 million new vacant units that would be associated with the elimination of a shortage would be in addition to the supply of additional occupied homes they estimate.

In any case, they are clearly closer than any other reputable source to the true answer.

I have poked around data in various ways. One way to come up with a broad estimate is to compare real expenditures on housing to real total personal consumption expenditures. In other words, how has the quantity and quality of our homes grown relative to the quantity and quality of everything else.

And, also I compare rent inflation to the inflation from everything else.

These are in Figure 1.

Real expenditures is down about 23% since 1990. If changing preferences were driving this, these measures would tend to move in the same direction. (Declining demand would lower both prices and quantities.) Obstructed supply moves them in opposite directions.

Rent inflation has accumulated to more than 35%, once you account for recent lags in the data.

The combination of less housing with higher rents means higher total spending. Demand is inelastic. When supply declines by 1%, rents rise by more than 1%. So when we have less housing, we spend more, in total, on it. That is why it is wrong to argue that building more homes won’t systematically lower real estate wealth. It absolutely will. If we build 20 million homes, the total real value of structures will obviously rise. The total value of real estate, even including those 20 million homes, will decline. That must mean that aggregate land value will decline sharply.

I think some people get too deep in the weeds thinking about specific dynamics of construction in very specific locations in, say, Brooklyn or Oakland, and lose their grasp on the scale of the national market and the condition of the average neighborhood.

Anyway, just doing a simpleton’s elasticity estimate from Figure 1, those trends would suggest that each 1% drop in supply is associated with almost a 2% increase in rents, which is in the range of demand elasticity usually estimated for housing. If all of the decline in real housing was expressed through fewer units, the 23% drop would amount to about 40 million homes.

I don’t make a habit of claiming we are 40 million units short, but in order to argue that the shortage is of a lower scale than that, either in units, quality, size, etc., you need to argue that the BEA mismeasures it or that something changed in the way that Americans consume housing, that just happens to mimic the quantity and price changes that would happen with a supply shortage with normal estimates of demand elasticity.

Everyone is welcome to make those arguments, and I will accept them. You will need to make them, to get the estimate of the shortage down to 20 million units. I will give you my argument below.

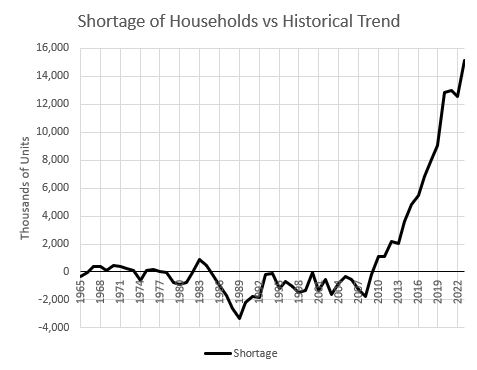

Another way to make a broad estimate of the shortage is to compare headship rates to historical trends. Adults per house (including vacant homes) was on a linear, slow downward trend for decades. From 1965 to 2008, it declined from 1.87 to 1.64. Most of the decline in household size has been due to fewer children. Including both adults and kids, persons per home had declined from 2.96 to 2.19.

Then, when a generation defining financial crisis, a deep crackdown on mortgage lending, and an 80% drop in single-family home sales all happened, the trend in adults per home reversed. We still have declining numbers of children, so, when you see supply deniers claim that we have more homes per capita than ever, they are referring to persons per occupied home, including children. Their claim is true using that metric.

Figure 2 shows how many more homes we would have if that linear 4 decade trend in adults per home had continued. If the trend had continued, we’d be down to 1.59 adults per home. Instead, we have moved up to 1.76 adults per home. The shift is so sharp, and the cause of it so obvious, that I think this actually makes for a reliable stab at the number.

About 15 million missing homes is a bit more than 10% of the housing stock. In Figure 3, I compare the shortage of units to the rise in excess rent inflation and the rise in excess real estate value, relative to incomes. (Here, I have adjusted the real estate value to make it credit and cycle neutral, using the Erdmann Housing Tracker estimates.)

Now, the thing is, real expenditures on housing started to decline in the 1990s, and rent inflation started to accumulate by then. But, the decline in housing units relative to the trend implied by adults per home didn’t change until 2008. So, here, again doing a simpleton’s estimate of elasticity, I am going to treat the 2002-2012 level of rents as the benchmark.

The 10% shortage of homes since 2008 has been associated with a 25% rise in rents.

I find, generally, that each 1% rise in rent inflation (rising rents with no improvement in the structure) is associated with about a 1.6% rise in values. So, the 10% shortage of homes has been associated with a 40% increase in home values (25 x 1.6).

So, I would argue that each additional home has a very strong effect on rents and home prices, and even with that, it would take 15 million homes to get back to what was normal until 2008.

But, what about rising rents and prices before 2008?

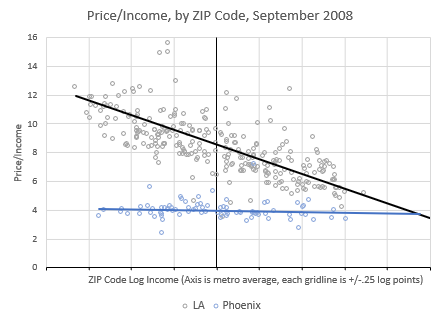

Figure 4 compares price/income ratios across Los Angeles and Phoenix in 2002. And, this gets at the caveats about the Corinth and Dante paper.

Migration from LA to Phoenix was heating up by then, and you can see how the process happens. LA has a housing shortage. Where you have a housing shortage, rents and prices get bid up, regressively, as families systematically compromise down into the existing stock of homes, giving up some amenities in order to budget high housing costs. In doing so, they drive up the rents and prices in the neighborhoods they are compromising into.

Along that path of compromises, families select to either pay more, compromise locally, or move away from Los Angeles entirely. At any given point in time, the price of homes in Los Angeles has little to do with the generalized amenities and quality of life in Los Angeles. It is simply the reservation price of the next marginal family in Los Angeles for accepting regional displacement.

And, when the marginal family makes that move, a home gets built in Phoenix.

So, I would argue, along the lines of the caveats to the Corinth and Dante paper, that, as of 2002, Los Angeles had a deep housing shortage, but the United States didn’t really have a shortage. The high costs in LA reflect the local shortage, but it’s not really an equilibrium price. It’s a very slow-playing disequilibrium.

If those migration pressures ever dissipated, prices would slowly normalize in Los Angeles. Those aren’t a market price for Los Angeles amenities. Those are the market price for idiosyncratic endowments that displacement takes away from individual families.

Those high prices aren’t the result of some generalized demand elasticity. Nobody else is bidding up the value of living close to your grandma. The households acting on the market based on generalized demand elasticity are moving into LA from Atlanta or Indianapolis, in any case, generally. Their demand elasticity determines how far down within the Los Angeles market they are going to apply compromises to lower the cost of their unit. When they move to LA they accept a worse house than they would have in Indianapolis. How far they have to compromise down is determined by how high a price the next marginal family has to suffer before they give up the endowment value of home. The price is determined by the leavers, not the arrivers.

The effect it has on the consumption of housing from newcomers is primarily played out through the type of unit they move into. Households are very pliable about the real housing they consume. That’s why historically the Case-Shiller index was so stable and nominal spending on housing had been so stable. We want to spend about 9% of GDP on housing, and markets in equilibrium will revert to that where possible. So, newcomers are willing to give up a lot more on the real amenities of housing to move into LA than they are willing to give up in, say, groceries. Someone with a good job offer in LA will move into a home with 1/3 the square footage of their old home, but they wouldn’t accept an 800 calorie diet.

That means that the shortage of housing in LA doesn’t really reduce the domestic in-migration that much. It only reduces it if it lowers the quality of housing that the newcomer would have to compromise to so low that it would be unacceptable to the potential newcomer.

And, there you go, that’s how real housing expenditures could decline by 10% before 2002 or 2008 while rent inflation had accumulated 15%, and yet I would agree, there wasn’t really a housing shortage, in terms of units. A house was built in Phoenix. The price in LA isn’t really a supply/demand issue. If people didn’t feel those endowments of long-term location, family connection, etc., then as soon as LA prices moved up a dollar, someone would just move to Phoenix. The price differential between LA and Phoenix, in that context, is not a measure of supply/demand. It’s a measure of inertia in the process of change under duress.

So, the shortage today is only 15-20 million units.

But, note, there was still a shortage in 2008. The shortage is expressed through quality - the family earning $120,000/year, spending $4,000 in rent on a 1,600 square foot house in LA, when they could be paying $3,000 for a 3,000 square foot house in Phoenix.

So, while the net number of units that the American housing market could easily absorb is something in the 15 to 20 million unit range, the amount of residential investment it could absorb, in order to fully reverse excess rents and prices is equivalent to something akin to 40 million units worth of construction and improvements.

Normalization in Los Angeles wouldn’t just mean an extra 3 million residents living in new homes. It would also mean a bunch of 1,600 square foot units becoming 3,000 square foot units. Really, I think it would be hard to accomplish one without the other.

Normalization in Los Angeles would mean a bunch of poor families whose rent would fall by half and a bunch of rich families who would double their housing size and quality while spending the same, and every other family would be somewhere between those two extremes.

By the way, this means that people who say, “Only build affordable homes, not luxury homes” are actually blocking the only functional process for healing and affordability. An affordable Los Angeles will include rich families living in better homes and poor families spending less. Both parts of that pair would be the result of a normalized LA.

Conditions in Los Angeles had gotten worse by the financial crisis. As of September 2008, the gradient in LA had gotten steeper. Phoenix was still flat. So, the shortage in Los Angeles was even worse, but there still was not a national shortage. Houses were still built in Phoenix. Families in LA were just paying more of “a bribe to the land” not to be the next one displaced.

Again, that’s not so much an equilibrium condition. It’s a disequilibrium. It is associated with a flow, not a stock value. The slope steepened and the flow of families away from it increased.

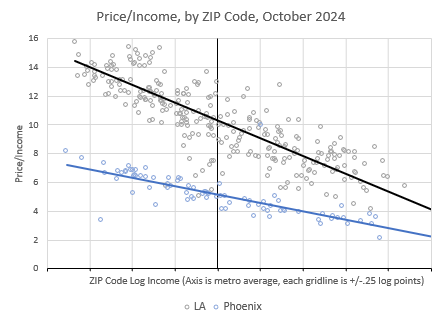

Figure 6 shows conditions today. The mortgage crackdown created a nationwide housing shortage. Now families in every major city have to make compromises down into the existing stock of homes in order to economize. In every city, families have to pay a premium in order to stay close to grandma, or a job, or friends or schools, etc.

I think we can treat this as sort of a binary issue. Before 2008, high rents only meant local shortages, not national shortages. After 2008, the rise in rents and prices is fully a reflection of a national shortage. If a family moved from Los Angeles to Phoenix in 2002, the line flattened a bit in LA but stayed the same in Phoenix. Today, it flattens in LA but rises in Phoenix.

I think the 15 million missing homes suggested by the trend shift in adults per home (say 10 million households and 5 million vacancies, give or take a couple million) are sort of a disequilibrium just like these sloped price/income patterns are. It isn’t so much a settled supply and demand condition. It’s a shock that has happened faster than families could adjust. Market frictions. Inertia.

Now that rents and prices are high enough that there is a new source of housing that is both legal and financially viable - single-family homes built at scale to rent - the demand for those 15 million units will be expressed. There is little we could do to stop it, short of making this last form of housing illegal. We will to some extent. Maybe we will completely. But, until we do, more building is going to happen. And, maybe with YIMBY wins the number of multi-family units that can be produced each year will also start to grow.

When we’ve produced 15 million of them, we can revisit the estimates. We’ll know by then if the typical city’s price/income slope is relatively flat again, like most of them were before 2008.

I think that if we don’t fix the mortgage market, we still will demand 15 million additional homes. Rents will be higher. The units will be a bit smaller. It’s basically like increasing the cost of construction. Instead of more expensive lumber, homes will have more expensive management costs, losses from principal-agent issues, etc. But households will still want to be households. So, it might be that 20 years from now, there are 15 million extra houses, but the real expenditures and rent inflation measures from Figure 1 are still relatively far apart. The houses will be smaller and their rents will be higher. But there will still be houses.

The difference between a market with historical ownership rates versus a more renter-heavy market is the rent required to induce a buyer. Landlords require higher rents for the same house than owner-occupiers did under 20th century borrowing standards. So, the 15 million extra homes demanded will fetch prices similar to what they did in the past. The Case-Shiller index will mostly normalize, in other words, in cities that don’t have land use obstructions. But, rents might still be higher. But now, those will be rents on the structure, not rents on the land. So, price/rent ratios won’t be elevated, and the price/income line within amply supplied cities will be relatively flat, like Phoenix before 2008.

I think if we follow all those factors to their end-game, even if we don’t return to 20th century mortgage access norms, the rental market can reverse the regressive home price trends American cities have had over the last 16 years. Of course, renters will be worse off than homeowners, and the regressive effects of that will remain. So, today, in Figure 6 you can see a continuous function of the regressive effects of the housing shortage in LA and Phoenix. A rent-focused building boom will flatten those lines (or at least the Phoenix line), but within each ZIP code there will be a discrete difference between families that are allowed to experience the advantages of homeownership and those who are not. The latter will pay higher rents because of that.

Very interesting but I want to push back on the language of how many houses we "need". In my experience talking about how many houses are needed encourages a view amoung the general public that development plans should figure out how many houses are needed and only authorize development for that many rather than just zone to allow building and let the market determine if it makes economic sense to build more.

And yes, there is obviously going to be some socially optimal level of housing so I don't mean to suggest anything is wrong with what you said but I just think it would be better to talk about how many houses would be ideal as I think people react to that language differently.

Kevin, have you ever looked at permits versus population growth? I was hoping to produce a graphic that supports the lack of houses, but I do not believe it does. Since 1960, the median number of permits (FRED: New Privately-Owned Housing Units Authorized in Permit-Issuing Places: Total Units (PERMIT)) per person of population growth is .53 (or 1.88 people per permit). The median is skewed slightly above the average (permits / person). Any thoughts on this?