I thought there might be a need for a brief explanation of the use of the word “shortage”.

“Shortage” is a loaded word among economists. Scarcity rules the world, so we are always “short” of everything, in the colloquial sense. And, a common response to my work is that there are so many homes and so many people. Some homes and locations are better than others. Some homes fetch a higher price, and it may be that some homes are expensive because they are in places where it is hard to build more. That’s not a shortage. It’s just a market.

I have decided over the years to fully own the “shortage” verbiage, because it is a shortage in many ways that are technically signals of shortage. Homelessness, long queues for subsidized units, long queues for permits, and economically motivated migration are all forms of non-price market reactions that are common when price or quantity restrictions cause a shortage in the strict economic sense (of distortions preventing price and quantity settling at its natural equilibrium).

There are direct practical ways to see that housing has a shortage, too. One common way to create shortages is to set a price cap. In the most expensive cities there are many projects working through local political processes trying to get approval, and possibly the most common complaint and reason for denying them is that locals complain that the price is too high. In that process, both a price cap and a quantity limit are being arbitrarily created as sort of an emergent phenomenon of local democracy. If there are units that aren’t getting built, or are delayed, in your city because “the price is too high”, or “these are luxury units and what we need are affordable units”, etc. then you have a housing shortage that seems to me to fit the pedantic definition quite directly.

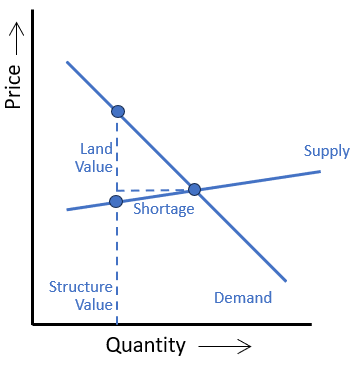

I think in real estate, it is very easy to see and measure how it is a “shortage” in the traditional way. Where there is a shortage of any good, the quantity gets pushed to the left of the natural equilibrium point. The cost of production goes down the supply curve. And there is some market friction that creates that gap (for example, a maximum quota on quantities).

In housing, this is pretty easy to measure. When there is a shortage because of a supply obstruction, land value becomes inflated. The gap between the cost of production and the market price is land value.

And that is the basic logic of the tables I have been posting. My estimate of the shortage is my estimate of how much land value is elevated, and how many units it would take to get rid of that elevated value.

In a true shortage, since the market can’t clear through price, something else has to serve the rationing function. Usually it is a queue, or buyers might engage in lobbying or bribery to get access to supply. I think you could think of the shortage in housing as paying a bribe to the land in order to buy the structure.

Agglomeration Value

That’s why inflated notions of agglomeration value are so troublesome. The “superstar city” claim is that the land under expensive homes is just really valuable. This is just a market price for great locations.

And the association of agglomeration with density also confuses matters. It’s just more expensive to build above a certain level of density, so the added cost of dense cities isn’t land value. It’s structure value where great locations lead to more dense and more expensive building. That’s one version of the agglomeration story.

But, my model is basically measuring the value of land under homes in the suburbs and exurbs. Short supply causes a peculiar pattern in home prices. Land across an inadequately supplied metro area rises relatively uniformly in value, which means that formerly cheap homes increase the most, in percentage terms. Most of the signal of elevated land value in my model comes from single family homes where multiplexes could easily be affordably built if they were legal.

Until 2008, there was an amazing coincidence where the cities with the most apparent value also had the worst supply conditions. Now, since 2008, it would appear that every city has attained more agglomeration value, and the scale at which they have attained it has been correlated with how badly their local supply conditions were hurt after 2008.

A lot of coincidences. Or maybe it’s been supply conditions creating a shortage that leads to “bribing the land to buy the house” in every case.

Rent Control

Rent control presents an interesting case here, because rent control would normally be a textbook cause of shortages. In those cases, the quantity supplied moves to the left because the price is held artificially low. Normally, this leads to queues, bribes, and declining quality of supply, which includes things like attracting abusive landlords to the market.

In housing, declining quality of supply is an automatic response to rent control because homes naturally depreciate. Landlords normally have to reinvest in their properties in order to justify asking high market rents. If rents are kept low, landlords will let the property decline to match the price.

The odd thing about rent control in the current market context is that these markets are already in a shortage condition.

It is true that if there is already a shortage due to supply obstructions, then rent control isn’t necessarily going to push supply even lower. But, the “bribe to land” is a market-determined price. Putting rent controls on a unit can’t lower the land value. It lowers the willingness of the market to supply and maintain the structure, just the same as it always does. So, we should expect all the same outcomes that we normally expect of rent control. Deteriorating units. Abusive landlords. Etc.

Putting rent control on a unit in a supply constrained city just leaves you with the same elevated land value plus an artificial discount on the structures. If supply is effectively a constant, then maybe rent control won’t change the total number of units, but it will likely bring other common side effects.

In limited contexts, where the tenant’s binding issue is rent expense, that may be preferable to the tenants. In this way, rent control may be an economically dubious policy in amply supplied markets, but in undersupplied markets, letting the structures decline in value to offset the rising cost of land might save the existing tenants from regional displacement. Of course, it doesn’t reduce displacement, though. It just changes the victim. As long as the quantity of homes is being limited in any manner, below the threshold required for stable population and household formation, displacement is inevitable regardless of rents and prices.

Mortgage Access

Another confusion here is how we tend to discuss homeowners. The thing that differentiates a homeowner from other families is that they are a supplier. The academy seems to have been in the habit of treating homeowner purchasing demand as largely a proxy for demand for shelter. But buying a better house is an increase in both supply and demand.

Locking households out of borrowing had much more of an effect on supply than it had on demand. They are supplying nothing now, but they are still demanding something near what they demanded before.

All of the frictions created by this extreme shift in norms have created conditions similar to the conditions created by urban land use obstructions. Preventing homebuyers (suppliers) from buying structures has temporarily (on a very long time frame) created a market condition where tenants (both owners and renters) have to “pay the bribe to land” to live in the existing homes that are available.

I think that will slowly play out over time and the “bribe to land” will decline. Under current conditions, it will just eventually lead to higher rents across the board. Allowing more generous lending will lower rents. And in the meantime, the shock of supply was so sharp that it has created shortage conditions nearly everywhere.

Table of Shortage Estimates

Finally, here is the table with shortage estimates for the 30 largest metro areas. Here, I have added back in Philadelphia, Detroit, St. Louis, and Pittsburgh. I had left them out of earlier versions for technical reasons, but the way I ended up displaying the shortages, I don’t think the bias I was worried about in the data matters much.

I am confused by the following comment, which is something I have seen echoed in a few of your articles, "The thing that differentiates a homeowner from other families is that they are a supplier"

I thought home-builders would be the only suppliers in this context? Are you referring to families who build custom homes?

Orthodox macroeconomists dislike the word "shortage," except when describing "labor shortages" in the US.