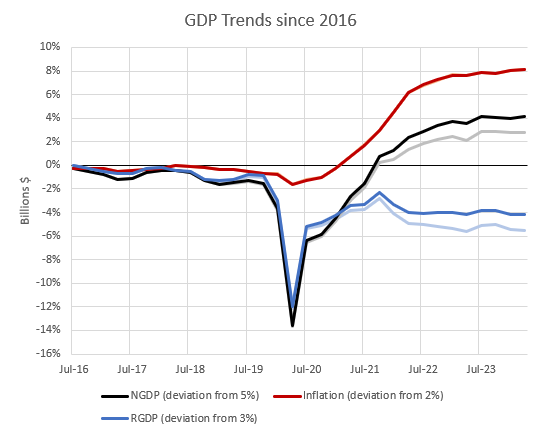

The BEA just published revised GDP estimates, and the main change was that cumulative real GDP growth from 2020 to today was revised up by more than 1%. Figure 1 shows GDP since 2016, relative to stable trends. The previous estimates are in the lighter shades. Estimated inflation did not change at all. Real growth was revised up. And, so, nominal GDP was also revised up.

The Fed targets 2% inflation, so by that standard, monetary policy has been too loose by 8%, both before and after the revision.

I prefer the NGDP growth target that market monetarists like Scott Sumner support. Before 2008, that had been associated with 3% real growth and 2% inflation, for a 5% nominal growth trend. That’s what I use in Figure 1. Scott has lowered his estimate of a neutral growth trend over time. He now uses a 4% trend. He has already posted a reaction to the revisions. He considers recent Fed policy to have been too loose. Before the revisions, it was 10% too loose (NGDP was 10% higher than a 4% trend would be). Now, he says that it is 11.5% too loose. He says that the Fed got lucky because unexpectedly strong real growth kept inflation lower than it would have been.

Practically everything I know about monetary policy I learned from Scott. And, he is light-years ahead of the rest of macroeconomics. The standard line among economists is that the Fed brought down inflation in 2022 by raising the target interest rate. That is as incoherent as it is popular. Long story short, a 1.25% target rate (which is what the Fed Funds Rate was at in June 2022 when the monthly inflation path returned to normal) cannot plausibly lower inflation that is near 10%.

I agree with Scott that the Fed was loose in 2022. We just disagree on the results. I think that was a good decision, based on the outcomes. Scott would have preferred lower growth.

I have several reasons for preferring the 5% trend. I think the 2008-2016 period was an aberration. Real growth was low because of deep regulatory suppression of mortgage access, an unsustainable depression in construction, the frictions created by choosing to put 2 million construction workers into long-term unemployment, and the nominal drag created by the one-time destruction of $5 trillion of the wealth of working class homeowners.

I also think inflation has been overstated for the last several decades because rent inflation has been biasing stated inflation higher. Under the conditions of political supply constraints, rent inflation is mostly inflation of rents on the land under the house. It isn’t inflation of production (which is, after all, the “P” in GDP). Supply-triggered rent inflation is a transfer to the troll under the bridge rather than a change in the nominal cost of production.

This sort of rent inflation should not be counted as part of nominal production. That’s tough to do statistically. But, at least we should remove rent from price indexes when considering monetary policy. Imputed rents of homeowners are frequently excluded from international price indexes.

Now that residential construction is at least back up to what would have been recessionary in the 20th century, we should expect 3% real trend growth again until proven otherwise. And, inflation excluding rent has been below 2% for much of the past 30 years, so there is room to increase nominal growth compared to recent trends. I don’t think there is any reason to be hasty about lowering our real and nominal production expectations outside of the context of the unsustainable depression of the 2010s.

By the way, if there is any way that we can start to reverse all the accumulated rent inflation, my inflation target that excludes rent will actually call for tighter monetary policy than the standard measures will. Let’s hope that I get the chance some day to advocate for tighter monetary policy.

Figure 2 compares the nominal GDP trends from the 2008 recession and the 2020 recession. Given that inflation expectations have remained firmly around 2%, I think the bit of overshoot we have experienced (relative to my preferred 5% growth path) has been reasonable. Even good. Certainly better than the growth path after 2008.

Currently, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tool is forecasting nearly 3% real growth for the 3rd quarter of 2024. I think we will have a string of quarters with GDP inflation below 2%. There is still transitory inflation left to give back in categories such as automobiles and residential investment. And, I expect real growth in residential investment to rise as the last of the supply chain bottlenecks loosen up and the prices of residential inputs decline.

So, I expect cumulative inflation to decline from 8%, even with the soft landing and renewed growth. The distance from where we are to a neutral nominal GDP trend is a bit longer after these revisions than it was before them. But, if we end up with strong housing construction, stable employment growth, and firm inflation expectations after all of this, I don’t see how anyone could have expected better than what JPow! has pulled together. If average nominal GDP growth from 2016 to 2026 ends up being 5.25% instead of 5%, and if core CPI excluding shelter or CPI excluding shelter averages 2.5% or less over that decade, put JPow! in the Hall of Fame.

Scott Sumner is great. George Selgin also has good stuff in his backlog and his books. In some of them he essentially advocates for a flat ngdp trajectory, ie 0% growth. Any productivity increase (and thus also any rgdp growth) leads to a price decrease in this regime.

His book 'Less than zero' explores the consequences and also looks at historic examples, like during some parts of the classic gold standard. (Scott Sumner wrote a new foreword to the re-release of the book a few years ago.)

Am I being a simpleton if I make the claim that all persistent inflation in our modern era is excess rents in shelter? After all, we can expect productivity gains in every other product and service, but regulatory induced scarcity in housing ultimately defines where we live, when to have children and how many, and distorts our collective perception of value.