Expensive Cities Aren't Attractive Cities: Follow Up

I just happened again upon a fantastic post from earlier this year from Ned Resnikoff titled, “YIMBYs are Proving the Fatalists Wrong: A response to Steve Randy Waldman”

I, like Ned, “was particularly dismayed by a recent attack on the YIMBY position from Steve Randy Waldman, a writer who I admire and usually find to be a careful, rigorous thinker.”

Ned’s post is worth reading in its entirety. Also, my previous post is what has me thinking about this issue. Also, Waldman has a reply to Ned’s post. And, finally, Ned has a reply to that, where he cites, skeptically, one of my posts.

I should probably start there. My post was pushing back against YIMBY triumphalism. There are markets where new rents suddenly take a 5% or 10% drop, and when they happen in places that plausibly have YIMBY policy trends, YIMBYs take victory laps. My point is that housing supply works slowly. It will be a huge victory if we can persistently get national production up to 2.5 or 3 million units a year. And if we do, that might flatten rents for a couple of decades and get us back to normal.

That’s what winning will look like. Supply isn’t going to make home prices drop 15% in a year. I wrote that prices won’t “collapse”. Supply won’t be disruptive. But it, absolutely will lower housing costs, and in fact, you probably won’t find someone with more radical views on that than I have. I think if we added 20 million homes to the US housing stock, the total value of residential real estate, even with those homes included, will be nearly half what it is today. All I’m saying is that will take decades. It’s not going to happen overnight. The value of a home, as an investment, is (or should be) the rental value it provides to the family that lives in it, not capital gains. The total return that homes provide to their owners over those decades will still be perfectly reasonable. They just won’t come in the form of capital gains.

Ned summarizes Waldman’s argument:

So why not rely on private actors to build at least some of the housing we need? To Waldman’s credit, he does not pretend that the housing shortage is a mirage. Instead, his anti-YIMBY argument relies on three futility theses. Thesis 1: YIMBY land use reforms will never happen. Thesis 2: Even if they do, developers won’t take advantage of them. Thesis 3: Even if developers do build, low-income renters won’t benefit. None of these are new arguments; after the events of the past few years, it’s time to put them to bed.

And, he notes one of Waldman’s claims, that “private developers will only reinforce geographic inequality by concentrating economic activity in what are already America’s wealthiest, most productive cities.”

Superstars

Waldman made the following comments in his original post:

The core problem we face is much bigger than land-use. It is geographic inequality. We have created a country in which too few patches of geography are associated with vastly better opportunities and amenities than all the other places. As with individual inequality, some of this is "natural”.

And:

So long as just a few places offer so much more amenity, liveliness, and economic opportunity than everywhere else, supply growth in those already built-out places will nowhere near match the tsunami of demand they face from people who would migrate there if they could. The deep flaw in YIMBY-ism is that problem they accurately highlight is orders of magnitude larger than what the solutions they identify, promote, and support can plausibly address.

This is what I was trying to address in the previous post. There’s just no evidence for this except for vibes. There are certainly some people who would like to move to San Francisco or New York City if they could afford it. A “tsunami”? This is a claim that is so far out of sample, it is effectively non-empirical.

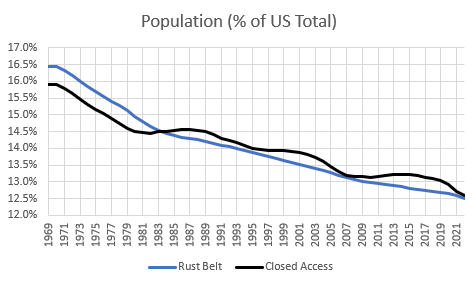

Figure 1 compares the collective population of the Closed Access cities (New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston) to the population of the major Rust Belt cities (every major city north of Kentucky, from Philadelphia to Kansas City).

First, you have to remember that the Closed Access cities were declining along with the Rust Belt cities for decades before everyone decided they were super. Back then it’s because they were in actual decline. Crime was terrible. City governments were going bankrupt.

Then, their population stabilized in the 1980s, probably related to improvements from that condition. And, then they returned to relative population decline by the end of the 1980s. (Even by 1990, though, they were hardly seen as successes. The movie “Grand Canyon” was released in 1991.) They started to get noticeably expensive in the 1990s.

There has never been a time where these were vibrant growing cities stretching to accommodate hoards of opportunity seekers. During the 2000s housing boom, their population stagnation actually intensified. Population change went negative then, and it is even more negative now.

Over the time they became expensive, they have been the slowest growing cities in the country. This isn’t a subtle question. There has never been a period of unusual in-migration or job growth in the Closed Access cities. There have only been very normal rates of in-migration that rammed up against very abnormally low rates of population growth.1

The differences in average incomes between the Rust Belt and the Closed Access cities has mostly been a product of who moved away. Not who was moving in.

All the amazing opportunities are figments of imagination. Maybe it’s true. It’s not falsifiable, because nothing remotely like anything that could prove or disprove it has ever happened.

It is quite possible that even 2% growth would have been enough to stay affordable. That might have stopped the actual “tsumani”, which has been the millions of former Closed Access residents moving to other cities. We are now 15 years in to the post-2008 regime, where many other cities are starting to become expensive, too. We have a growing database of “places becoming expensive”. And there has never been a single one that grew more than 2% annually.

Figure 2 is an actual “super” city, and I suppose it’s what people think the San Francisco chart looks like. Austin has grown more than 2% annually. It didn’t get expensive.

This is why I harp on this all the time. People like Waldman have given up on the most comprehensive and obvious solutions to the housing crisis because of an assertion that they can’t possibly confirm.

I have been comparing Los Angeles and Phoenix in the previous post. Figure 3 is a comparison of price/income ratios across Phoenix in 2002 and 2021 and Los Angeles in 2002.

In 2002, private builders were making Phoenix perfectly affordable across the city. By 2021, Phoenix home prices looked very much like Los Angeles had looked in 2002.

Is Phoenix now hopeless too? Did Phoenix get super? Was 2002 Phoenix a utopian dream that is unachievable now that high prices have proven that Phoenix is now also just so damn awesome?

No. And nobody would even make that claim. The “superstar” city claim is all vibes.

And, please understand. I am not challenging the vibes. You can love LA. You can think it’s the most awesome place that everyone would want to live. Just don’t pretend that on this specific, empirical question of what makes LA expensive that you’re making anything close to an empirical claim.

Figure 4 is a comparison of housing permits in Phoenix and Los Angeles. In 2002, Los Angeles was that expensive after spending years only approving 2 homes per thousand residents. In 2021, Phoenix is that expensive even though it has been approving almost 10 units per thousand residents.

If either of these cities actually has a claim on the idea that they would need to build for a tsunami, it’s Phoenix. Phoenix actually tried! Surely, we can presume, if demand curves slope down at all, that if Los Angeles had built 10 units per thousand residents in the years leading up to 2002, that it would have made some difference in housing costs.

This is a comparison we can make, in sample. Where there is some history of data comparing demand for living in Phoenix with demand for living in Los Angeles, Phoenix had the harder task of it.

This also relates to the third thesis Resnikoff mentions. I actually think he understates the progressive outcome of private development. Phoenix building collapsed after 2008. That is the difference between 2002 and 2021 in the chart - the entire difference. The result of not building was deeply regressive.

And, furthermore, where does he Waldman think more families were being displaced? Phoenix 2002 or Phoenix 2021 or Los Angeles at any point? It’s not even close. The local types of displacement created by building are a small fraction of the displacement caused by not building.

Builders

Waldman also makes the following claims.

The YIMBY dream is that, if regulatory constraints were lifted, swarms of home developers would engage in ruinous competition to build, driving down the price of the goods they produce and sell. In our contemporary, highly consolidated, economy, how many industries work like this?

And:

It’s a cliché that the government builds “bridges to nowhere” that the private sector never would build. That’s true. And it’s a credit to the public sector. Bridges to nowhere are what turn nowheres into somewheres. We need many, many more bridges to nowhere.

Phoenix in 2002 was a real place! I lived there! And, I guess I have to remind Waldman that the whole world thinks that Phoenix in 2008 was a giant housing “bridge to nowehere” built by an out-of-control private sector. Of course everyone is wrong about that. They are wrong that it was speculative building in a place nobody wanted to live. They were wrong that it had to be “ruinous”. But it certainly was true that developers engaged in competition to build, driving down the price of the goods they produce and sell.

And, today, builders are literally bidding up the prices of construction inputs, and have been for several years, trying to push the quantity of homes they are building above the current capacity to complete them. In all of modern economic history, there has never been a worse moment to try to argue that homebuilders routinely use market power to limit production.

I realize upon re-reading that “never” is too strong a word. Obviously every city permitted new housing at some point in its history, or it wouldn’t be a city. Los Angeles managed it until the 1980s. San Francisco did until the 1960s. The last decade New York City grew by more than 2% annually was the 1920s. Boston did in the 19th century.

But, since the vibes just feel so right, I’m sure that New England just reached its carrying capacity in the 1890s with the 10th largest metropolitan area in the country, and there’s nothing we can do about it. The same with the other expensive cities. And, then, in a wild coincidence, the entire rest of the country hit its carrying capacity at exactly the same time in 2008.

It really is ironic. Except for LA, none of the Closed Access cities became especially expensive before the 1990s, in spite of decades of exceptionally low growth. The only way that could have happened is if they were clearly not anything special, for quite a while, in spite of all the advantages of size and density.

Then, after decades, they recovered from that malaise, but none of them can grow faster than, say, Columbus, Ohio. And a whole academic field grew up to fawn on them.

That line: "...a ruinous competition to build..." sums up nearly all the misconceptions about the conditions prior to the Great Recession and a large part of the malaise we're suffering through now. A ruinous competition to grow food, make steel, and provide clean water to hundreds of millions of people is a fundamental principle of modern society.

The Club of Rome cultists who cheer the decline in the U.S. fertility rate are at least more consistent in their ideology than racist Boomers who oppose upzoning and immigration. That these two groups are united in opposition to reform of land-use regulation is one of the strangest political marriages in America. My only consolation is that this voting bloc is older and dying.

Another great post, KE. A frame I find useful for poking at Waldman's "Futility Thesis 2" (that builders left to their own devices will throttle supply anyway): generic market structure analysis.

As is the case for the vast majority of products in modern economies, the market for housing is Monopolostic Competition. So: many existing suppliers (and relatively low barriers to new entry) offering similar but differentiated products to buyers. Vectors of differentiation provide the individual firm a bit of pricing power but only a bit.

Left to their own devices, the hallmarks of this sort of market is fierce competition between sellers and abundant choice (in both quantity & quality) for buyers. Holding together the kind of cartel necessary to throttle supply in this sort of market is a mathematical impossibility: too many actors to coordinate and the rewards for defection are far too great.