Expensive Cities Aren't Attractive Cities

Yesterday, Nolan Gray asked for nominations for the most underrated city. Josh Barro replied with “Los Angeles”. Matthew Yglesias replied with “I think we often underrate how highly rated Los Angeles is — it’s the place people are most willing to immiserate themselves in order to live by a large margin.” and he posted a list of cities with the highest home price/income ratios, and Los Angeles was the highest.

Using Scott Sumner’s parlance, I replied that he was “reasoning from a price change”. High prices can mean low supply or high demand, so we need to know about quantities before assuming the motivations for high prices.

He replied, “I’m just saying we observe a high willingness to pay to live in Los Angeles that seems to be driven by amenity value rather than high wages.”

It is not driven by amenity value. Matt can be forgiven for thinking this. Most of the urban economics academy has been “reasoning from a price change” for 30 years. He could probably call up the economics department at Harvard, and they would assure him that yes, obviously, cities are expensive because they have massive amenities.

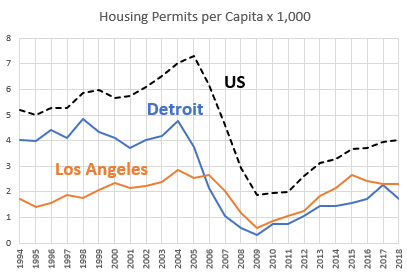

I decided this would be a good chance to walk through a visual that I hope helps think through these issues.

Demand never makes a city expensive. A lack of demand can keep a city from being expensive.

In Figure 1, the blue dots are from 2002 and the orange dots are from 2024. Population growth is on the x-axis and average price/income ratios are on the y-axis.

You know those Case-Shiller charts that people like to share? Where housing in the US is flat, flat, flat, for decades - centuries - and then suddenly at the end of the 20th century, it jumps up?

That is because in all of history, every city was somewhere on a line between 2002 Pittsburgh and 2002 Las Vegas. If they had great amenities, they grew. If they were struggling, they didn’t. And they all had relatively affordable housing. If any group of major cities had even moderately become more expensive, as they had started to by 2002, then the Case-Shiller index would have been volatile then too.

The only way that the Case-Shiller chart can look like it does is that no amount of demand, progress, amenities, agglomeration, etc. etc. etc. has ever made cities expensive.

If you limit housing so harshly that it affects migration decisions, then you get expensive. You move to the left (less growth) and up (more expensive). This has happened across the country since 2008. I added the US average estimates there. Since 2002, the US has moved to the left and up. The US hasn’t added amenities since 2002. We broke our housing industry and stopped building adequate housing.

If Los Angeles built enough housing, it would show up somewhere around Houston. If Houston cut off growth, it could be Los Angeles.

Demand interacts with this. Pittsburgh can’t currently become LA by blocking housing construction. But, the cities in the top left are not any more special than, say Austin, at least. They might be special, but not so special that 2% or 3% annual growth wouldn’t handle it.

We can see this historically. As late as the early 1990s, Los Angeles was basically where Houston is in Figure 1. Then, it moved to the left and up. To a first approximation, all a supply phenomenon.

These are extreme trends. Nobody has to p-hack anything here to see what’s going on.

Also, all of the cities at the top left, with growth rates well below 1% annually, have massive domestic outmigration. They are bleeding people. And, the price/income is systematically negatively correlated with local amenities. It is the worst neighborhoods that have the unusually high price/income ratios. In LA, the neighborhoods you would least like to live in have price/income ratios in the teens. Those are also the neighborhoods where the most families are moving away from Los Angeles.

Price/income ratios are high for one and only one reason. People have a lot of endowment value in the homes and places they live, and housing supply in this country has gotten so bad that it is forcing people to be displaced for economic reasons. They are willing to pay a lot to avoid that. Much more than they would pay for sunshine and cool beaches. LA is expensive because of how far left it is in Figure 1. It is expensive because of displacement.

Figure 3 also includes Phoenix. In 2002, Phoenix was flat. Then, after 2008, we made it much harder for families to get funding to build houses. Housing construction in Phoenix collapsed.

Did Phoenix suddenly get better amenities? Did the poorest neighborhoods in Phoenix especially get better amenities? Or did Phoenix move to the left and then move up in Figure 1 because of supply constraints?

Again, you can see in Figure 1, the path Phoenix has taken is not particularly different than LA’s. If Phoenix spends the next decade blocking any population growth, it can get an average price/income ratio of 10x too. It’s gotten 1/3 of the way there just by growing less than 2%. We now have conducted this natural supply experiment long enough and widely enough to get good estimates on this.

I forgive everyone for having such a hard time with this. The problem is that the economics profession, understandably, believed what they were seeing with their own eyes, and they have been Ptolemaic on this. When an economist sees Figure 3, their mind immediately starts working on extra epicycles, to make it make sense.

We don’t have to do that. The sun is not circling us. I know I’m telling you that your very eyes and the world’s top experts are lying to you. Just wonder for a second. Just a second. What would it look like if we were on a spinning ball, and it was us who were circling the sun?

In a second, the epicycles drift away. All the complications are gone. It’s all easy. Because for a second, you held truth in your imagination.

Los Angeles is great. Lovely place. Maybe even one of the best.

But, the reason the average price/income ratio there is 10x instead of 4x is that the guy who walks into the U-Haul office next week to find out that it costs twice as much to rent a U-Haul out of LA than it does to rent one into LA, really, really, really, didn’t want to move away from his college buddies, his parents, and the local machining industry that he had spent 30 years building a career in. But, LA finally broke him. LA is expensive because it breaks people.

LA doesn’t have a particularly high number of people moving in. It does have a lot of that guy. The Ptolemaists imagine that a lot of people want to move in. And that’s why there are still Ptolemaists. At this point, the epicycles that explain how special Los Angeles is are purely imagination, existing far outside the sample space. Nobody had to record celestial movements to add that epicycle. They just had to imagine what people would prefer if we lived on a different celestial body - one where LA permits houses.

On ours, it doesn’t. That’s the story on our planet.

PS: Some charts for the comments.

I've only ever had two economics courses, 50 years ago, but I have been saying for a while, my neighborhood in Boston isn't being gentrified. It's the same worn, struggling place it's been for decades, it's just getting tremendously more expensive. Which I think is the gist of this post. And it explains a lot, thank you.

I also think inter-regional variation is often lost in these conversations. As someone living in LA, I strongly suspect that the coast has such a high amenity value that people will continue to pay sky high prices to live there even when building restrictions are lifted.

But within the county, there are plenty of places with pretty mediocre amenities where houses cost a million dollars, and that is mostly supply restrictions. I live between a highway and Amazon warehouse, and houses are just under a million