Why are homebuilder rate buydowns effective?

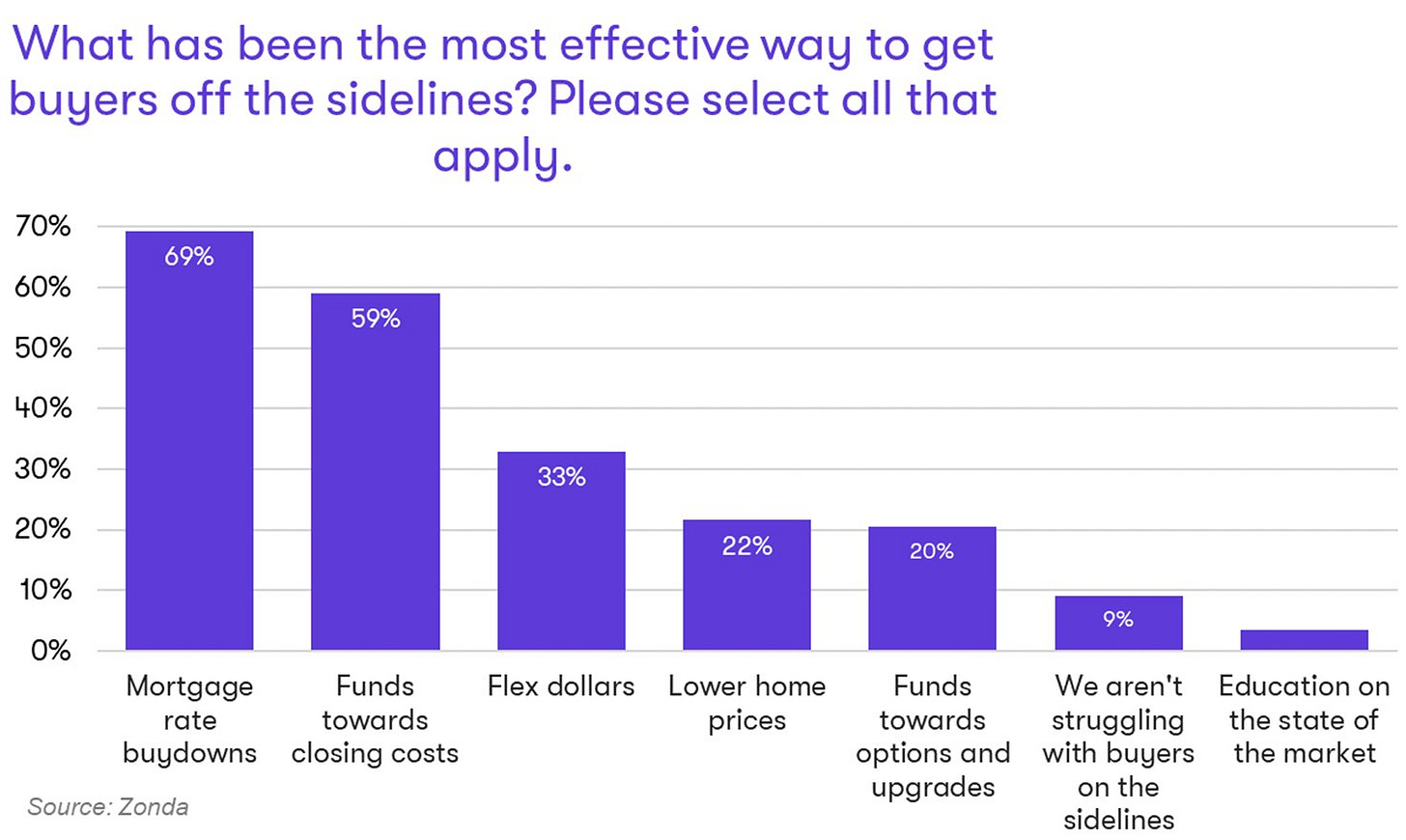

Here is a graphic from Ali Wolf, the chief economist at Zonda.

The textbook way to clear a market is to change the price. So, there are two questions here. (1) Why not change the price. And (2) If not, why is the most popular alternative mortgage buydowns.

Let me preface this with a note. I am just using intuition, and a bit of financial education, in this post. I have been in the business of faulting various popular financial intuitions long enough to know that’s dangerous. I welcome any comments anyone with insider input might have either for or against my intuition.

Maybe what follows is obvious. Maybe it will be interesting to some of you.

Why not change the price?

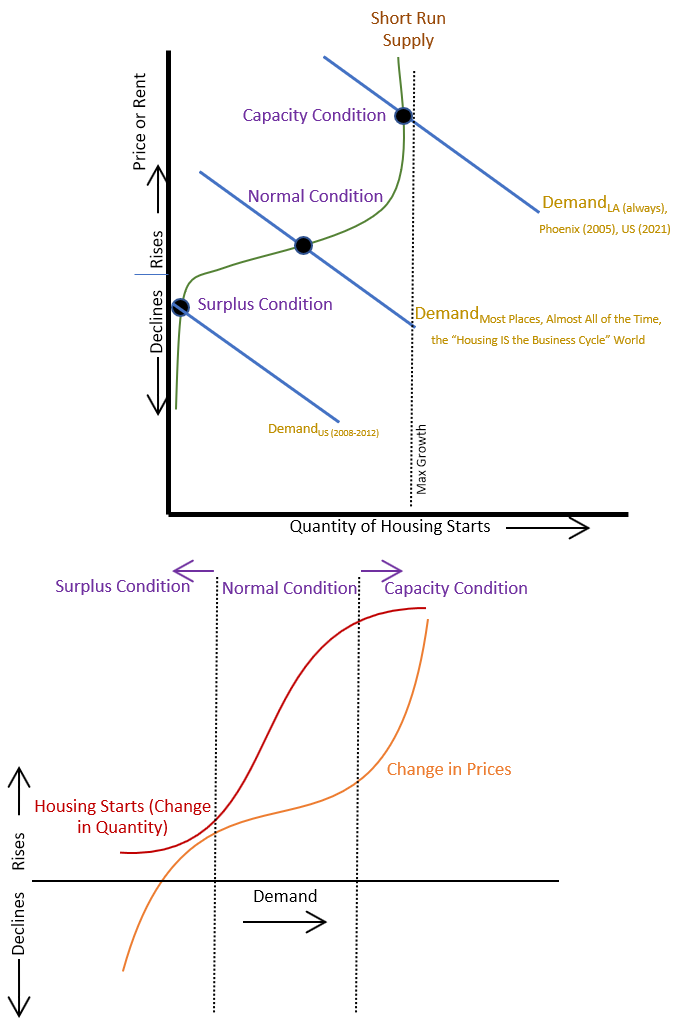

We have just come out of a unique period where supply chain disruptions created persistent supply constraints that applied nationwide. Before 2008, housing supply was a local issue. Where home prices were high, it was due to local regulatory limits to growth. In Figure 2, we were at the right side of a normal condition (where we should hope to be!), and our problem was that some cities keep pressing the boundary between the normal condition and the capacity condition to the left. After 2020, our problem was that the entire country moved into the capacity condition.

The owners of the constrained asset where local rules create the constraint are existing land owners. So the gains go to them. Local land prices inflate. Where a national supply chain disruption was the constraint, the gains went to homebuilders with supply chain access. So builder margins inflated.

You can see this in the costs and profits at Hovnanian. Other builders follow a similar pattern. In Figure 3, you can see that by the 3rd quarter of 2020, Hovnanian was selling more units than they could build. The backlog started rising while the actual homes under construction remained flat. This simply increased the queue time for homes to be finished. That peaked by the second quarter of 2022.

A couple quarters later those costs and revenues are recorded when the homes are finished. In Figure 4, I track profits and costs per unit with a simple linear inflation adjustment (so that some of the rise in costs is related to the general rise of inflation in 2021 and 2022). Two quarters after the rise in sales, profits and costs started to rise. Builders like Hovnanian were engaged in a bidding war for supplies to try to shorten their inflated production queues, but there was no point in selling homes they couldn’t build just to bid away all their profits. The long queues were risky for the builders. So, the market equilibrium settled where costs increased, but profits increased too. Then, two quarters after the backlog peaked, in the 4th quarter of 2022, profits peaked.

This leaves the construction industry in an odd place that I don’t think it has really seen before in the modern era. As these temporary costs unwind, the competitive price level of new homes will decline. This isn’t related to a normal decline in demand. It’s just an unwinding of these transitory supply constraint costs.

Declining home prices are problematic because they create stresses and frictions for builder sales. Who wants to put a deposit down on a house that is going to be selling for less by the time it is finished? Current buyers might want to renegotiate. (These are probably reasons, in addition to interest rate concerns, that more sales are being made with partially constructed homes than with unstarted homes.) This may be an important reason why in the business cycle, sales usually decline earlier and much more deeply than prices do. Instead of buying into a declining market, buyers wait. Construction slows down until prices rise or stabilize.

In 2008, it was correct to argue that home prices, broadly speaking, don’t go down. (It still is! 2008 was the exception that proves the rule!)

Another reason that home prices tend to remain level is that homebuilders only accept so much gross margin compression. Below a certain price level, they also choose to forgo sales. When there are minor fluctuations in price, builders smooth those fluctuations with less transparent changes in net pricing - incentives on upgrades, rate buydowns, etc. And, currently, we have a unique situation where prices are declining in a market that isn’t in cyclical decline. Prices are falling but sales are not. So, those non-transparent attempts at stabilizing neighborhood prices in new builder communities are important in a way they never have been before. A stable or growing construction market is still apt to be paired with builder costs that are quite a bit lower than they were a year ago.

One reason I think this is worth discussing is that a lot of analysts and homebuilder insiders will incorrectly attribute this to falling demand from rising mortgage rates. If that was the case, sales would be declining more than prices are. The core reason for the current market conditions is that costs and builder margins were temporarily high. This is a subtle distinction. A whole book could be written about the interaction between the business cycle, interest rates, and construction. I can’t get into all of that here. But, this is a subtle distinction that can give you a trading advantage because I am pretty sure most insiders and homebuilder executives would tell you that high interest rates cut demand and this is an interest rate story. That’s all you need to explain why rate buydowns are popular. I’m an armchair analyst who doesn’t understand what’s happening on the ground.

You can see the unique situation in Figure 5. This compares existing home prices -Case-Shiller (an average) and Zillow (a median) - with new home prices (average and median).

First, there are some telling historical trends here. In the pre-2008 boom, it was all about local supply constraints, so existing homes increased in value more than new homes. Broadly speaking, where homes could be built, prices were more moderate, and where homes couldn’t be built, existing homes became more expensive. And, since expensive places were becoming more expensive while most of the country remained relatively moderate, average prices (which are influenced by the skew of very high priced homes in the average) moved higher than median prices (which are not).

Then, when mortgage suppression after 2008 killed the bottom tier of the new single-family home market, the average and median values of of new homes rose, because buyers for low-tier homes couldn’t get funding. At the same time, mortgage suppression drove the prices of low tier existing homes down. Eventually rental values on low tier homes increased enough to pull their prices back up to the market equilibrium with new homes.

Then, after 2020, prices on all homes spiked. And, finally, this year, new home prices dropped while existing home prices remained relatively level. Some of this is compositional, as credit-constrained buyers compromise down to units with lower prices or forgo some upgrades. But, it highlights the historically unique nature of this development and the downward price pressure on builders.

Why buy down the rate?

So, builders have an incentive to fill in a temporary gap between the market price of new homes and the temporarily higher market price of similar homes built last year. Why use rate buydowns instead of other incentives?

This is because of another oddity in the current marketplace, which is transitory inflation and the oddball yield curve. Figure 6 shows the expected future short term rates at 4 points in time. (For example, on May 31, 2022 - the green line - a bank could enter a contract to borrow cash in the future, in March 2031, at a rate of 3.6%.) I have also noted the fixed rate at those 4 points in time on a 10 year Treasury bond and on a 30 year mortgage.

At the end of 2021, future expected yields were low across the board, and the yield curve had a common shape. One reason mortgage rates are higher than rates on Treasuries is that mortgage borrowers can refinance if rates decline. Investors call this Prepayment Risk.

A loan that receives 6% interest becomes more valuable if after it is originated market rates decline so that new loans only receive 4%. And, it loses value if the market changes so that other loans can receive 8%. Each 1% future rise in the market rate lowers the value of both 30 year mortgages and 10 year Treasury bonds by about 7%. This doesn’t matter to Treasury bond investors. Say you invest $100,000 in a Treasury bond. There is a 50% chance that rates go to 4% and a 50% chance that rates go to 8%, it all evens out, and the bond that pays 6% is worth $100,000.

Mortgages are different than bonds. If the mortgage pays 6% and the market rate goes to 8%, the mortgage will only be worth, say, $86,000 if you want to sell it to other investors. If the market rate goes to 4%, then the borrower will refinance, and you just get your $100,000 back. This is different than a regular bond. Here, the average expected value is $93,000, so in order for the investor to be willing to loan $100,000, they need a 1% premium to make it worth $100,000. So, the mortgage rate must be 7% instead of 6%. (I am greatly simplifying here, of course.)

At the end of 2021, there was little risk that interest rates would ever go low enough to worry much about prepayments. So, the 1.8% spread between a 3.3% mortgage and a 1.5% Treasury bond reflected other costs of mortgage lending. That has been a pretty normal spread over the past 20 years.

As short term rates increased, and the Fed pushed its target rate above the long term rate, the yield curve developed this weird shape. It is inverted, which means that it is downward sloping. That usually signifies a coming recession. But in this case, the bump at the short end is related to our recent transitory inflation, after which rates are expected to decline and take a normal shape again.

There are several issues at play here.

Short term rates declining over the next couple of years as inflation passes will mechanically have some effect in lowering the future market rate on mortgages.

Normally, rates would only decline in recessionary conditions, but in our current odd situation, rates are likely to decline in recessionary conditions and even in several growth scenarios.

The novelty of our situation and the recent volatility in both inflation and interest rates increase the uncertainty about how much rates might change.

All of these factors increase Prepayment Risk. And, so since the end of 2021, the 10 year Treasury rate has gone from 1.5% to 4.3%, but the 30 year mortgage rate has gone from 3.3% all the way to 7.2%. Almost a 1% increase in the spread. Much of this is due to Prepayment Risk.

So, let’s say a builder is in a position where they need to offer incentives.

They could just offer upgrades, etc., but they could also offer a rate buydown. Let’s say the builder sells you a house with a $100,000 mortgage, and they give you a 5% rate instead of a 7% rate. All else equal, they will take a loss of $14,000 on the mortgage in order to give you that rate.

But, with the rate buydown, there isn’t much Prepayment Risk. If market rates go down from 7% to 5%, the borrower will just keep paying 5%. So, the mortgage is more like a regular bond, because of the rate buydown.

The combination of having some room to negotiate on the net price, after incentives, and the ability to reduce risk for mortgage lenders, make this a popular tool for builders. The peculiar shape of the yield curve and the high premiums for Prepayment Risk make this an especially useful tool.

Prices are moving up again, so the motivation to offer more incentives than normal will slowly recede. But, I suspect, even if the gap between the gross price and the cost of new homes to the builders closes, rate buydowns may continue to be a profitable tool for builders to use until the funny bump on the short end of the yield curve works its way out and mortgage spreads return to normal.

In the meantime, these tools mean that the de facto mortgage rate on new homes is probably closer to 6% than 7%, in terms of how much house the borrower can buy with it. It’s the current market rate on mortgages that is the outlier here, and these arbitrage tools are just one way to rid the market of the anomalous risks that have pushed mortgage spreads up. All else equal, the correction from here will be a return to lower mortgage rates with more normal spreads. Eventually, when mortgage rates return to normal, these tools will not be as useful.

Conclusion

It seems straightforward to observe that rates shot up so builders are buying rates back down as a reaction to that. But, the reasons for rate buydowns are more subtle than that. You’ll probably see a lot of folks who make the sort of mistakes I discuss here a lot, who only see the simple story. They already have a false sense that prices were inflated by artificially low interest rates, and so this fits a narrative where the builders are using rate buydowns as a sort of replacement of the Fed’s low rates, to keep some sort of unsustainable boom going. At some basic levels, none of those observations are entirely wrong, but they are all wrong in subtle ways. They add up to a mistaken Gestalt, which provides you with trading opportunities where these confusions are deeply shared enough to distort markets or nudge sentiment.

I remember taking the re-fi train on a little downward journey between 2010 and 2012ish. I recall that in 2010 we were happy to get 5.5% on a 30yr fixed. A year later we were happy to drop a 100 basis points and get a drop in the monthly payments going forward. We were happy a year later when there was another 100 bp drop. We did the math long term and it made sense both times, and the local bank seemed happy with to slurp up the transaction costs each time--they were just selling the note back to BB&T after each closing.

The 30 year mortgage is a convenient fiction--no one ever pays them to full term at the starting rate--but everyone understands it as a tool for assessing payment capacity of a homebuyer. The buydown makes sense as a sales tool and if it wasn't sustainable in the short term for the builders they wouldn't be using it. Because of the training I've received from this source and others I don't think Fed actions are going to have much impact on lending rates over the next 18 months. However, I think that high rates--even with buydowns--will eventually start a downward trend. Of course, I'm just blowing smoke because I've grown up in a low rate world.

The reason to use rate buydowns rather than price reductions is not as complex as you make it out. The rate buydown does more to lower the monthly payment on a 30-year amortizing mortgage. With amortization, repayment of principal is backloaded, and payment of interest is front-loaded. In an inflationary environment, lowering the interest rate does more to reduce the upfront burden. A lot of homebuyers are payment-constrained, so this enables them to buy the house.