Update on rent trends, through September 2023

I’m seeing a lot of claims about a building boom leading to lower rents, and that builders are going to slow down because of it.

EHT readers can agree that recent rent and price trends appear to reflect more construction, and for the first time in years excess rent inflation may be moderating. There is little reason to expect aggregate multi-family construction to decline significantly below current capacity, however. I think that is an ahistorical expectation that comes from some of the myths which I push against at this newsletter.

One of those myths is that the slowdown in construction after the Great Recession was due to industry consolidation and capital discipline. Figure 1 compares trends in (left axis) single-family, (right axis) multi-family, and manufactured housing production per capita.

First, manufactured homes got the 1-2-3 punch. First, they got federal regulations in the 1970s meant to make manufactured homes less viable to stick-built homes. Then they were subject to the same sorts of local obstructions that multi-unit buildings get (keepin’ out the riff-raff). Then, they were hit with the same financing obstructions that killed single-family construction after the financial crisis. It’s such a dangerously affordable source of housing, Americans have managed to attack it on several fronts.

As I point out endlessly, the permanent drop in single-family production was due entirely to mortgage suppression which caused existing home prices to drop in areas with low incomes and entry-level new single-family construction to dry up. After 2008, high-end borrowing, and high-end prices and production basically moved along with multi-family trends.

The decline in multi-family building was later and shorter-lived than in single-family, and the recovery has been stronger. In multi-family and high end single-family, mortgage access didn’t create a one-time scar in the market. Reports of housing’s death have been greatly exaggerated. Given the long-lead times and cyclical concerns of producers in multi-family, it is notable that the dip associated with the Great Recession came later and recovered more strongly than single-family….until it hit the hard cap of regulatory constraints that have kept total multi-family construction at a fraction of the levels common before 1990.

As for today, a key factor to keep in mind, given this history, is that production is not limited by demand, or by cost, really. I need to write a more detailed piece on that idea, to walk through what I mean by it. But, for today’s post, I will just repeat a point I have probably made before. As a meta-level piece of logic, it is implausible that, short of a shock and a temporary disequilibrium, the economic processes that created the richest nation in the history of the world would leave capacity for new housing untapped while thousands live on the street and rents take an outsized percentage of the average household’s income. If your model tells you it will, then your model has problems. A lot of housing models have a lot of problems.

Furthermore, on its own, multi-family construction doesn’t amount to enough housing to create a strong downtrend in rents at the macro level.

I think there are at least 5 biases affecting analysis, currently.

The point discussed above, that consolidation, capital discipline, etc. have been given too much attention as reasons for low recovery in construction since 2008.

Money illusion. Inflation spiked and now is declining. Much of the change in rent inflation is related to that rather than supply.

Rent inflation base rates. Rents have been persistently rising much faster than general inflation for 8 years. Even a relatively sharp downshift in rent trends, that would be palpable for industry insiders, could continue to accumulate excessive rent inflation.

Cost base rates. Current industry insiders are coming off years of highly advantageous conditions that were, themselves, unsustainable. Benchmarking to those outcomes will make a sustainable market seem like a negative shock.

Recency bias. The numerous failures that followed 2008 are attributed to investor error - dumb money coming in late when a correction was baked into the cake. That’s a misreading of history. A widely shared misreading can have a marginal effect on investment. (For instance, it has left some homebuilder stocks undervalued.) But, that won’t necessarily flow through to aggregate construction. For instance, homebuilders are building at capacity, in spite of undervalued shares. And, even if the sentiment is deep enough for existing players to reduce new production, new players might enter. They will be dismissed as dumb money, but under current conditions, it’s hard to know how much capital has been on the sidelines because of supply or regulatory capacity. It’s like letting up on the accelerator when you’re already passed the speed governor.

These are just my guesses of reasons why there could be biases. I could also be wrong, or have my own biases.

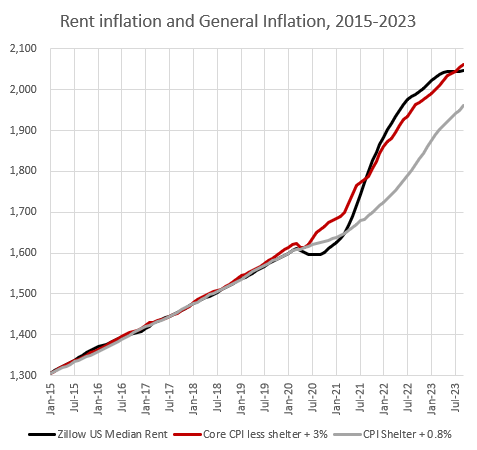

Regarding the data, Figure 2 conveys some of my position on this. This compares the change in Zillow’s US median rent estimate to the CPI shelter inflation component and CPI core inflation excluding shelter. Here, I have added 0.8% annually to the CPI components so that CPI shelter matches the Zillow measure from 2015 to 2019 (which is mostly due to the CPI measuring apples-to-applies, while Zillow includes compositional changes). In addition, rent inflation has been just a bit more than 2% above non-shelter core inflation since 2015, so I added that amount to the core CPI ex. shelter measure. In other words, these are the relative price trends if there is persistent 2.2% excess rent inflation.

Lags in the CPI shelter measure make it inaccurate since 2020.

By the way, you can see here that there is still about 4% of cumulative lagging shelter inflation left for CPI to capture to catch back up with market rents. So, Fed hawks have about 1.6% of future fake aggregate inflation to pretend the Fed still has to tackle. I’m pretty sure JPow! is above all that, but there will probably still be a few months of monetary policy coverage where there will continue to be misplaced suspense about whether the Fed can finally put a stop to the inflation that ended 15 months ago.

Figure 3 shows the 12 month trailing inflation rates.

You can see how the CPI shelter is a lagging indicator of market rents, which didn’t matter as much before 2020. You can also see the unprecedented levels of persistent excess rent inflation before 2020, which many industry insiders are likely benchmarking to. You can see how market rents took a brief dive in 2020, then, recovered, partly to simply correct back from 2020, and partly overshooting general inflation. As you can see in Figure 2, the overshoot was pretty minor. At its peak, in early 2022, cumulative Zillow rent inflation was about 2% above the cumulative core inflation + 3% trend. And, on a trailing 12 month basis, Zillow rent is just now merging with non-shelter core inflation without any excess.

Figure 4 compares the 3 measures without the 2.2% persistent excess adjustment to the non-core CPI measure excluding shelter. This is the cumulative price change from 2015 to September 2023 in rents compared to the cumulative price changes in other core CPI items. It’s about a 20% difference.

Here, you can see that in the last few months, rents have finally leveled off, suggesting that it is possible that new construction might start bridging the gap.

Figure 5 shows the cumulative excess in rents since 2015 - the percentage difference between the red and black lines in Figure 4.

The problem is that all of the mythologies in the misguided conventional wisdom about the 2000s housing boom and bust add up to a lot of confusion. The idea that housing supply is on a cliff’s edge, and if you build too much, you induce a deflationary spiral. The idea that “late-cycle” investments have it coming. The idea that builders cut back by choice, rather than because buyer funding was cut off. Etc.

Remember, the supposed sage of 2008, Robert Shiller? His entire warning about a housing bubble was that rent inflation, and thus home prices, revert to the norm. There’s nothing you can do to stop it. That’s the way it had been for a century. That’s why housing was surely in a bubble. Unless you’ve been cooking up your own heterodox take on the post-2000 housing market, this is what you believe.

Did that rule get overturned? Excuse me, did I miss the rush of articles about how Shiller got it all wrong? Do housing markets work now such that rents and prices just keep ratcheting up over time, and never reverting? Did everyone throw their “100 year real Case-Shiller price charts” in the garbage?

And, if you believe prices are too high, and that rents still revert, à la Shiller, back to normal price levels, how is that going to happen except for building more housing?

There is a lot more to say about why that will happen and why historically normal interest rates don’t change that. In the meantime, I would just suggest that you think really hard about whether any of these current claims about slowing construction fit coherently in their own right with your broader view of how housing works.

As of now, rent inflation is just normal - about where it should be in the long run, with a massive amount of correction left to realize. Starts in both single-family and multi-family are still basically at or above current capacity. The main questions will be, (1) how quickly can capacity and production rise from here and (2) who will fund and build it. It will be built. There is still room for corrections in regulatory delays and supply chain delays to lower costs, just from a status quo capacity view, even before hoping for YIMBY advances. And, at best, when it is built, the correction in rents will take years to play out, if not decades.

We may very well see rents decline from here, but if they decline sharply, it probably will be more related to Fed overcorrection into disinflation or deflation than to a building boom.