Transitory Inflation (March 2021- June 2022)

I thought I’d add a bit more color to my position on transitory inflation. The short version is that I was wrong about it, and it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter that we had it and it doesn’t matter that I was wrong about it.

The Fed Win: Rate Hikes Didn’t Lower Inflation

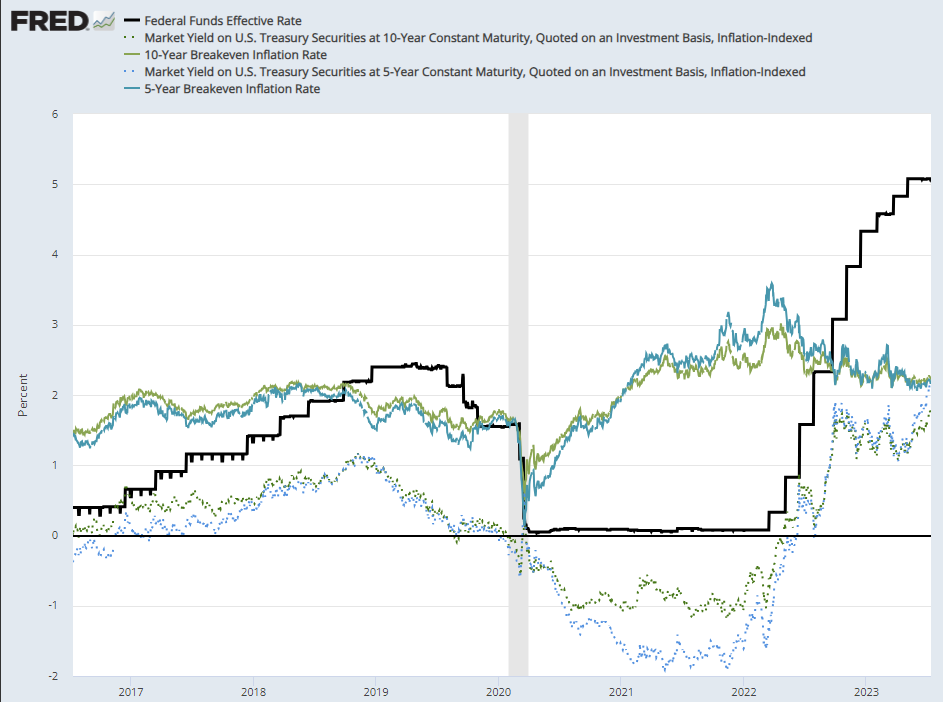

As a review, here are charts from my previous post on it. Figure 1a compares the Fed Funds rate monthly to inflation expectations and real long term interest rates (rates adjusted for inflation). Figure 1b shows annualized monthly CPI (excluding shelter) changes.

My take is that, after 40 years of Great Moderation (a big win after the 1970s), the Fed needed to show that they could watch inflation expectations tip a bit above their target (2% is their PCE target, which generally has equated to about 2 1/4%-2 1/2% of CPI inflation.) without causing them to panic us into a recession.

The Fed has plenty of credibility on keeping inflation below target. It was inflation that boosted the Fed’s credibility, and increased the odds that we can avoid going down the road that Europe or Japan have been in. Or worse, what we chose in 2008. Once they earned that credibility, real long term rates recovered sharply, because forward expectations recovered sharply. Higher long-term real interest rates are associated with more risk-taking and higher rates of shared economic growth.

For two decades, long term real interest rates have been low because growth expectations have been low. Many people treat interest rates as if they are a simple lever controlled by the Fed, with a stable neutral target level. This leads to a common fallacy that low rates are stimulative, and that we are in some sort of Ponzi scheme economy where the Fed has to keep pushing rates lower to stimulate, but that we keep getting less and less out of the stimulus.

Eventually, I’ll probably write whole series of posts about that, but for today, suffice it to say that “in this house we believe” that the Fed has little direct control over long term real interest rates.

Really, this has been a huge win for the Fed, because the Ponzi story would have just kept ratcheting up if they had tried to kill off inflation in 2021. Real rates might have stayed low, and when inflation subsided we would have been back at the zero lower bound. The Ponzi story would continue to appear meaningful. In that scenario, home prices might have even ended up lower than they are now, but they would still seem high. And it would be very popular to claim that prices are being inflated with ZIRP.

As I wrote about previously, inflation was transitory. Inflation expectations started to decline (see Figure 1a) before the Fed Funds rate was much above zero, and even inflation itself has been firmly at or below the 2% target since the Fed Funds rate was below 1%. Even the “expectations channel” can’t salvage Fed tightening as a cause of lower inflation.

It was transitory, in that it went away on its own.

Krugman and Moving Goal Posts

Paul Krugman might be a good jumping off point here. I think I basically agree with him about it. He tweeted:

Gotta say it: the original Team Transitory proposition was that inflation would subside without the need for a big rise in unemployment. Not looking so wrong now (supercore is core ex used cars and shelter, 6m annualized)

Caveats: this took much longer than expected. And the Fed did raise rates a lot, although it's fairly unclear how that reduced inflation. But the idea that we would face an ugly "sacrifice ratio" is looking hard to defend

He’s gotten some pushback for appearing to move the goal posts a bit. And, I agree, he has. Bob Murphy had a pretty good gottcha on this, noting a December 2021 headline reading, “Krugman Says He Got it ‘Wrong’ When He Repeatedly Called Inflation ‘Transitory’.” Murphy says, the clock ran out. The game is over. It’s too late to move the goal post. You already signed the scorecard.

As I noted, I was wrong about how much inflation there would be. I just don’t think it matters. Leave the goal post where it was. The inflationistas scored. I am reversing the goal on a technicality.

I Was Right. Then Wrong. Then Right, After All.

I am in Krugman’s position. There isn’t much of an internet record of it, but in the summer of 2021, I personally took a short position in Eurodollar futures (which profits from rising rates). I didn’t expect inflation, though. I expected the healing of supply chains coming out of Covid to create excess real growth.

It was the same take I have now. Inflation had already started to rise, and I could see that the Fed wasn’t going to squash it. They were going to let the economy, and the housing market, continue to press up to existing capacity and to draw investment into new capacity and real GDP growth. I expected inflation to settle and real growth to rise. Part of my position was in September 2022 contracts.

Figure 2 shows the price trajectory of those contracts. (In Eurodollar contracts, you subtract the interest rate from 100, so at the beginning of 2021, the rate on these was about 0.25% and by July 2022 it was 3.5%. I was short, which means I profited when rates increased and the contract price fell below 100.)

You can see what a killer position this was. I couldn’t lose more than a few hundredths of a point, and the experienced upside was more than 3.00.

But, alas, as Krugman had by the end of 2021, I also concluded that I had been wrong about inflation. (I also was in need of cash, and had to make some hard decisions in my portfolio.) I thought the position still might be profitable, but profit from higher inflation wasn’t my thesis. Real rates were still low. So, I unwound the position in 2021, telling myself it was the disciplined thing to do rather than seek sources of cash to cover a position that might be gaining in a way that wasn’t really a confirmation of my thesis.

Boy, I’d like to have that one back.

But, the real salt in the wound is that by the time those contracts expired, they really did confirm my original thesis. Interest rates in September 2022 were higher purely because of rising real long term rate expectations.

I had thought I was wrong, and now I will rotate again to claim I was right. And, it’s not just an embarrassing headline that haunts me. It’s the huge pile of profits I would have made if I’d stuck to my guns. I wish I only had Bob Murphy gottchas to worry about.

So, what was I actually wrong about? I was wrong about the Ukraine War. That’s forgivable, I think. I was wrong about the secondary waves of Covid that tied up supply chains longer than expected. In hindsight, we probably should have had more expectations about that. And, I didn’t put enough weight on federal fiscal stimulus. I don’t usually attribute much inflationary power to that, but in this case, the size and destinations of those funds were likely responsible for some of the excess inflation.

De Facto NGDP Targeting FTW

And, “neutral” is a bit of a slippery idea. Maybe a neutral Fed would have meant that transitory inflation reversed itself rather than just plateauing at a new higher level.

Here, I think the Covid recession is a “this time is different” moment.

At Econlog, Scott Sumner cited an interesting new paper from some Fed researchers. They measure shared vs. idiosyncratic changes in wages across sectors and attribute most of the sharp changes in wage growth to shared shocks, which Scott attributes to monetary policy. This seems reasonable to me.

Figure 3 is from that paper and that post. Basically, nominal wages are sticky downward, so when there is a negative shock to real GDP, wages don’t drop easily, and this leads to unemployment when the marginal value of labor is lower than the market price. So, the negative shared decline in nominal wages in 2001 and 2008 were related to negative real growth and unemployment. If the Fed had goosed nominal spending and inflation more, to make up for it and keep nominal wage growth above zero, there might have been less unemployment.

In 2021, the Fed pushed harder to raise nominal spending, so that wages didn’t just stabilize. They shot up.

In general, I think NGDP growth targeting is a vast improvement over inflation targeting, and especially over inflation targeting through interest rate manipulation. When a supply shock hits, it raises inflation. The 1970s oil shocks are good examples. Targeting inflation in that context means that other prices have to fall to make up for higher prices in the affected sectors. With NGDP targeting, inflation can be countercyclical, so that nominal incomes remain stable. If a supply shock is large enough to actually lower real incomes, because more of those incomes have to go toward energy, for instance, it doesn’t really help to also push down nominal incomes in other sectors to keep inflation level.

But, I don’t think nominal GDP growth targeting fully solves that problem. For instance, when there is an energy shock, spending on energy will tend to take a larger percentage of aggregate expenditures. So, if incomes are otherwise stable, spending on other sectors will still have to decline to make up for it.

So, we could make an excuse for higher inflation or higher nominal growth at any moment by pointing to some sectors as “supply shock” sectors, and arguing that inflation or spending in all the other sectors should be stable while we let that supply-related inflation run its course.

But, that’s probably a recipe for unmoored spending and ratcheting inflation expectations, like we had in the 1970s.

That’s where the positive growth target comes in. Something like 2% inflation or 5% NGDP growth mean that the sectors that are experiencing downward relative trends at any moment will still stay positive enough to avoid nominal dislocations that come with deflation (like wages that don’t adjust downward). So, we have the space to let some sectors deflate from the target rate without causing unemployment when supply-triggered inflation pops up in other sectors.

This is where the Covid recession was different. It was a major, temporary real shock, across a lot of sectors. We all really were briefly 10% poorer. The sectors with supply shocks were so numerous, and affected in so many ways, that I think this was a case where the most stabilizing policy response was one that aimed to prevent broad declines in spending by allowing a lot of sectors to inflate.

That’s a dangerous exception to get in the habit of, but clearly (1) Covid was a rare event calling for a rare response, and (2) we did it! Inflation expectations have remained anchored!

And, in the end, we have arguably remained pretty anchored to a 5% nominal GDP growth path. Arguably, the overshoot in nominal GDP has been really, quite small.

It seems to me that the remaining concerns about inflation rely on future trends. What if inflation or NGDP growth turn back up?

What sign is there of that? Trends in money supply aggregates? Labor markets? Interest rate policy since June 2022?

Fears about a resurgence of production or inflation seem weak. There even remains some built in deflationary potential, since there are areas, such as automobiles, that still have not recovered to normal levels of production or inventory.

Summary

The Fed didn’t have to fight inflation.

Holding their fire when inflation arrived, temporarily, was a major accomplishment.

Transitory inflation does imply that prices will reverse. In fact, some of that reversal is surely inevitably still to come in automobiles, for instance. On this point, the Fed did even better than letting transitory inflation play out. They have guided us back to trend at the higher price level, which has approximated an NGDP growth target. Covid made us poorer. An act of God, like a hurricane. As of today, we are at a lower real level of production than the pre-Covid trend, and the Fed allowed prices to counter that drop. As shown in Figure 5, real GDP is below trend and GDP price levels are above trend. This combination has produced nominal GDP growth in Figure 4 that is slightly above a 5% trend from 2016.

There is still potential catch up growth yet to come. In fact, I think it is likely. That should be able to happen with low inflation rates in the quarters ahead. And, I just don’t see how lowering nominal spending trends at any point over the past 3 years could have put us in a better position to do that. What exactly do the transitory inflation critics wish was different?

I expected that catch up in real growth to happen in 2022. I was wrong. World-wide forces intervened. First, came some transitory inflation. I gave up on my investment thesis that was based on real growth and I forgot about it. The Fed didn’t have that choice. They stuck with it, and let the inflation play out. We are all better off for it. It turned out I was right after all, but I was only right because the Fed guided the economy to the potential that I didn’t have the patience to wait for.

I’m not interested in moving goal posts. I don’t care if I was right. I didn’t execute my trade. I’d have rather been wrong. It would have stung less. My point here is that, I, like the rest of you, have been given better monetary management than I deserved.

I'd love to be a fly on the wall for a conversation between you and Arnold Kling:

https://arnoldkling.substack.com/p/disinflation-might-be-transitory?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=338673&post_id=135309525&isFreemail=true&utm_medium=email

Good post, as usual. I'm too afraid to make specific trades in anything. I do like to imagine worst case scenarios when it comes to Fed policy, because memories of the 2008 debacle are still fresh in my mind.

The most obvious Worst Case is that the Fed continues to raise rates through the end of this year and into the next, causing a real recession going into the election cycle. I put odds on that of about 50% which is higher than it should be. A continuation of this Worst Case is regardless of which political party wins, the Fed starts cutting too late and manages a repeat of the Great Recession. I put odds of that happening at less than 25%--partly because there's no "bubble" in any sector of the economy.

I guess what I'm saying is that the Fed got lucky in one direction, and might get unlucky in the other direction. Maybe I'm just pessimistic this morning.