June 2023 CPI Inflation Update

Boy, aren’t these exciting times for inflation updates?!

The Discourse© has been insistent on using trailing 12 month inflation as a benchmark so that, as of yesterday, there was still an air of concern that the June 2023 Fed Funds rate had still not managed to reduce inflation in June 2022. Fortunately, the update this morning, from which that last remaining month of excess transitory inflation finally fell out, didn’t come with any temporary positive noise, and it has left little ground to move the goal posts to in an effort to remain Concerned©. This appears to have had a positive effect on expectations and the yield curve.

Sorry. I shouldn’t be snarky. I realize it’s not the best way to convey a point of view to a skeptic. Anyway, the tl;dr on my point of view is:

I contend that 10 year Treasury rates didn’t rise because the Fed raised its Fed Funds Rate. The 10 year Treasury rate rose because the Fed didn’t raise the Fed Funds Rate. This led to a convergence back to healthy long term inflation expectations and less concern about an unnecessary recession.

Those improved expectations now called for a rate hike. Then, very quickly, between about March 2022 and October 2022, the Fed raised the target rate to about 3%, which is probably a relatively neutral level, reflecting the success of their earlier work. By then, inflation was over, so there was no need for a hawkish position. But, the Fed has continued to raise the target rate to 5%, which will be deflationary/recessionary if it remains in place too long.

I just don’t connect much with either side of what I’m seeing on Twitter inflation debates today. I think the restraint that the Fed showed in waiting to raise the target rate in 2021 and 2022 may have been the most consequential positive decision they have made in decades. It may have finally moved us off the zero lower bound.

Inflation was Transitory, you Knuckleheads

The black line in Figure 1a is the Fed Funds rate, the solid colored lines are 5 & 10 year inflation expectations. The dotted colored lines are real 5 & 10 year rates. Figure 1b shows the monthly CPI inflation estimate (annualized), excluding the shelter component.*

Let’s walk through what happened with hindsight.

June 2022 was the last month with a trend of excess CPI inflation. The Fed Funds target rate was still under 1% when that month began. Inflation expectations peaked in March 2022 and started to decline by the time of the first quarter point hike.

Keep in mind that the neutral rate is a moving target. For instance, a target rate of 0.25% when inflation is 10% is much looser than a target rate of 0% when inflation is 2%. In fact, that basically describes the shift in monetary policy in the period leading up to mid-2022. So, not only did inflation expectations and inflation itself subside before most of the Fed hikes. In real terms, by just about any specification I can think of, the policy rate in the spring of 2022 was looser than it had been in the months and years before.

The only way to concoct any version of events that attributes lower inflation to Fed action is to invoke some sort of “pet rock” theory of monetary policy where keeping the policy rate low increases the expectations that the Fed will raise rates in the future, and those expectations brought down future inflation expectations and real-time inflation itself while the Fed’s policy rate was at its loosest point in years.

I’m a big fan of the Great Moderation, but I think a plausible reading of this recent history is that inflation all along was transitory. It was going to come down without help from the Fed. By holding off on rate hikes, the Fed broke the trend of 3 decades that had become too hawkish. Hawkishness was an important element in the 2008 debacle. And, since then, inflation expectations were becoming steadily lower, below the Fed’s stated target. The temporary spike in inflation removed the zero lower bound problem and allowed the Fed to maintain a temporarily dovish posture that jerked long-term inflation expectations back up to the target. (Those long-term inflation expectations had nothing to do with the transitory inflation that allowed the Fed to lower its real target rate by standing still.)

When the Fed demonstrated that it had the patience to allow transitory inflation to happen without pushing long term inflation expectations even lower, the market reacted with optimism. This raised long term real rates sharply. And, when the Fed did finally raise its target rate, it was because, finally, a zero target rate was too dovish. But it wasn’t too dovish because of high inflation. It was too dovish because the Fed had successfully raised real rates by letting the market run and restoring faith in nominal growth expectations, and now rates could rise triumphantly rather than defensively. You can see the Fed target rate and real long-term rates rising in parallel in Figure 1a.

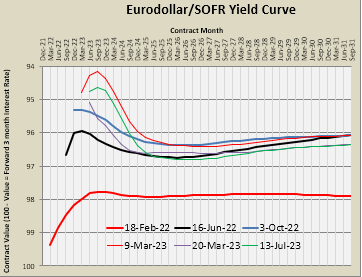

The long end of the yield curve has been relatively anchored at about 3.5% since the Fed Funds target rate was well below 1%. These are the rates most borrowers are paying. These are the rates driving mortgage payments higher. The sharp rise in the target rate since then is mostly meaningless. You can see this in the various yield curves over time in Figure 2.

Traditionally, when the Fed raises rates, the yield curve inverts as long term rates remain anchored by expectations. Then, when the Fed overdoes it, the whole curve tends to come down until they lower the target rate enough to trigger recovery. The change in yields shown in Figure 3 in the pre-Covid period were a good example of this normal process. It is an open question whether the Fed was lowering rates enough to avoid recession in 2020, because the process was interrupted by Covid.

In 2022 and 2023, the Fed’s target rate busted right through the long term rates, and kept going up while the forward rates remained near 3.5%. This is because Powell held off. This is because the Fed has re-established trust that they will err toward stable growth. The market trusts that these elevated rates are temporary.

So, this week’s CPI update finally pushed the last of the 2022 transitory inflation out of the trailing 12 month inflation measure. There are fewer and fewer backward looking concerns for hawks to keep a grasp on. And, so, as of July 13, 2023, the June 2029 SOFR contract rate settled at exactly 3.5%. And the rate on the June 2025 contract dropped by a full 40 basis points over the past 2 days. The CPI report gave Powell the cover to do the right thing and get the target rate back below 3.5% ASAP.

Maybe the best way to think about it is that J-Pow is da bomb, and now he has cover to keep being awesome.

I’m sure the hawks will find a few remaining Concerns© to slow the process down, but it has become more plausible that it won’t be slow enough to cause rising unemployment, declining housing completions, etc. Inflation has been over and done for a year and it’s going to stay that way. Inflation came down after June 2022 with a deeply negative real Fed Funds rate. Now inflation is going to rise with a 2%+ positive rate? Does anyone even actually believe in the inflation targeting interest rate tool?

An NGDP Targeting Perspective

Frankly, I don’t see any reason to switch from a good old-fashioned 5% NGDP growth target. Figure 4 compares nominal GDP to a target path rising at 5% from 1995, a 4% path since 2010, and a 5% path since 2016. I think lowering both the level and the rate of growth since 2008 is giving away the game. The choice of these trends is relatively arbitrary. NGPD growth seems to be sliding right back into a 5% growth path. I don’t see any strong reason to justify lowering nominal growth from this point (where both inflation and NGDP growth are basically back to normal).

Re-attaining a 5% growth path from 2016 is not a dovish position. That represents a 16% permanent drop from the pre-2008 trend! Most of that was a drop in real production and incomes! That is quite a hawkish concession! If this is the dovish position in 2023, what are we even doing?

The drop in production is even worse than it seems, because we count rising land rents as increased nominal production and income. Figure 5 shows the trend in CPI inflation over time relative to CPI inflation without the shelter component. In other words, this is a measure how much our consumption expenditures are inflated by the economic rents being transferred to real estate owners for obstructing the availability of housing. Depending on where you set your benchmarks, we are 4% to 6% poorer in aggregate because 4% to 6% more of our consumption is in the form of rent inflation, just since the 2008 debacle. The fact that many families are hedged by owning their homes and capturing these rents from themselves does not change the reality of that cost.

Calling for hawkish Fed policy because this is associated with inflated home values is not a healthy way to live your life, to say the least.

Figure 6 compares the growth of real housing expenditures (the actual size, quality, etc. of homes) over time based on a 2.5% annual real growth trend since 1995. We now have a 24% gap here from that trend. That amounts to another 2 or 3% of GDP. This isn’t in the form of a transfer of economic rents to real estate owners. This is basically just the deadweight loss of putting 2 million+ construction workers into long-term unemployment after 2008.

In other words, a good portion of the permanent loss to production and incomes after 2008 was due to our moral panic about housing construction.

In spite of ourselves, that is healing. Our cities are filling up with tent encampments, but at least construction activity has slowly recovered over the past 15 years, and it may finally be back to something somewhat sustaining. And, the 5% NGDP growth since 2016 coincides that that long overdue recovery.

So, no, I’m not going to make any apologies for retaining a 5% NGDP growth target. To go much lower than 5% is macroeconomic Stockholm Syndrome.

The fact that Jerome Powell led us back to that path, and, God forbid, even overshot it a smidge, is a miracle of leadership we frankly don’t deserve.

*The recent problem of the sharp trend shifts in rent inflation and the lag in the way the CPI survey method picks up rent inflation has made the shelter component especially inappropriate for timely monetary analysis. The Fed has been publishing alternative versions in an effort to address this problem. But, I have preferred excluding the shelter component for years now, when using the CPI for timely monetary policy analysis. This is for a number of reasons. One reason is that much of the component consists of owner-occupier estimated rent. This is a reasonable measure to use for analysis of cost of living over time. I think it belongs in the index. It just doesn’t have anything to do with short term fluctuations in nominal spending. In the manuscripts for both “Shut Out” and then in “Building from the Ground Up”, I had a chapter explaining why I think inflation targeting with a Taylor Rule should be specified with CPI excluding shelter. But, in both cases, I removed the chapter to maintain narrative flow on other more germane issues. Even in a nominal GDP targeting regime, I think a production estimate without rent and rental value might be preferable, but rents aren’t as significantly weighted in GDP as they are in CPI, so it isn’t as much of an issue.

Anyway, I can understand why it may look like cherry picking, since various advocates on both sides of the inflation debate have pulled out various versions of the CPI over the past few years to make dovish or hawkish cases, but it is a cherry I picked a long time ago and I have continued to use it because it’s a good cherry that always seems to make a better pie. I will still be picking that cherry when the next business cycle happens.

This is super interesting. I really hope that policymakers figure out that we need to let people build more housing rather than crushing the economy every 10-15 years because "those darned housing prices won't go down for some reason!!"

I really like that CPI-based estimate of land rents/how much poorer we are because we block housing production. I'm going to have to steal that!