In March, I wrote that inflation was over. Three months later, nothing has happened to turn me away from that conclusion. Three months later, policymakers and the commentariat still are oddly tied to backward looking measures like 12 month trailing inflation rates and to CPI shelter components whose lagging tendencies are broadly understood. So, from both the FOMC and its critics, there still seems to be a lot of worry about whether we can tackle the inflation that has now been thoroughly tackled for nearly a year.

(In case it is confusing, the subheaders in this article reflect conventional wisdom, but not my thinking.)

The Fed announced today that they would pause rate hikes this month, but reiterated that they might resume at the next two meetings. J Pow has been fantastic so far, and so my daydream is that he played up that possibility to get unanimity on this month’s pause, but that by the time those meetings happen, it will be difficult to justify more hikes, even with backward looking measures.

Figure 1 shows the cumulative inflation since 1995 for all items, for shelter (mostly rental value), all items excluding shelter, and core CPI excluding shelter (CPI less shelter, energy, and food).

The trends I have been writing about for a while continue. Shelter inflation (red), which is inapplicable to cyclical monetary policy for a number of reasons and which has been biasing monetary policy to be too hawkish for decades, is basically the sole source of above-target inflation now.

The comprehensive CPI measure (black) had a one-time spike that continues to rise at a rate slightly higher than target. The spike in comprehensive inflation stopped 11 months ago, so analysts that continue to use the 12 month trailing figure still have a bit of outdated overstatement in their number. That will finally be gone next month. But, even after getting rid of that problem, you can see in Figure 1 that CPI inflation for all items still continues to rise above the 2% trend. Even the lagged CPI shelter component will probably start to slow down in coming months. But, oh my, I just realized that we may have to endure months of analysts calling for continued monetary tightening while we wait on the excess shelter inflation to age out of the twelve month trailing figures. Dear Lord.

As you can see in the two blue lines - all items excluding shelter (light) and core CPI less shelter (dark), prices have been gliding along at something approximating 2% for 11 months now. Back in the 2000s, there was a brief rise in energy prices so that cumulative price trends for all items excluding shelter pushed a bit above the 2% trend and core CPI excluding shelter pushed a bit below it. We are back to cumulative price trends for both that reflect annual 2% increases in the intervening 20 years. That is a combination of below trend inflation in the 2010s when the mortgage panic led to shelter inflation and above trend inflation during the Covid supply channel disturbance.

The Fed Brought Down Inflation By Raising Rates

You will see a lot of discussion comparing the Fed Funds Rate to trailing 12 month inflation, and I want to push back hard against that. In a situation where consumer inflation has been demand driven and where it might be persistent, then it might make sense to assume that trailing inflation is important. But, if consumer inflation is due to a one-time supply shock, which will not persist, then it is inappropriate to compare trailing inflation with the current rate target. The real level of current interest rates will be determined by future inflation. The last 12 months is irrelevant. Judging current policy to be dovish because the current rate is lower than trailing inflation is begging the question. The Fed appears dovish because you have assumed that the inflation was related to dovish monetary policy. At this point, that is clearly a poor assumption.

In Figure 2, I compare monthly inflation (gray), 12 month trailing inflation (black dashed), the Fed Funds rate (red), the 10 year Treasury yield (dashed orange), and the 30 year mortgage rate (blue). Over the long term, the Fed Funds rate has tended to run a bit above inflation, though during the housing deprivation era in recent decades, it has tended to run below inflation, and both times when it moved up to the level of inflation, the yield curve inverted and a recession followed. (Yes, I know Covid happened.)

In Figure 3, I have magnified to just the more recent period.

If you compare the Fed Funds Rate (red) to trailing 12 month inflation (dashed black), it looks like inflation was high and, then, finally, the Fed started to raise rates to bring inflation under control, and slowly, it worked, until just in the last couple of months, the Fed Funds Rate has been higher than the inflation rate.

But, that story is purely a function of using a trailing 12 month inflation measure. Do you think borrowers and lenders setting interest rates for June 2023 care what inflation was in June 2022?

Using month over month measures, inflation abruptly stopped before rising Fed targets could have had much to do with it. And, Figure 3 uses the biased inflation measure that includes shelter inflation. Actual consumer inflation on cash transactions is lower than that. Since inflation did come down so sharply, the Fed Funds target was already into positive real territory (above forward inflation) by the fall of 2022. That’s why the 10 year rate didn’t rise much after that.

The Rising Fed Policy Rate Caused High Mortgage Rates and Long Term Rates

Here are the 10 year treasury rates in July 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2005 (2 years before rate hikes to 1 year after): 4.7%, 4.0%, 4.5%, and 4.2%.

The 10 year treasury rates in April 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023 were: 0.7%, 1.6%, 2.8%, 3.5%.

Fed policy in the 2000s was relatively tight because inflation remained moderate. Since a supply shock increased inflation in the 2020s, Fed policy was able to become more dovish just by standing still (the real rate declined as inflation increased). So, the 10 year rate increased by 2% before the Fed Funds Rate ever moved, and then rose another 0.7% after that.

First, this was from a rise in forward inflation expectations from levels that had become persistently below the Fed target, returning to levels consistent with the Fed’s stated target. Then, after inflation expectations had been restored, the real portion of 10 year rates increased by more than 2%.

I contend that 10 year Treasury rates didn’t rise because the Fed raised its Fed Funds Rate. The 10 year Treasury rate rose because the Fed didn’t raise the Fed Funds Rate. This led to a convergence back to healthy long term inflation expectations and less concern about an unnecessary recession.

Those improved expectations now called for a rate hike. Then, very quickly, between about March 2022 and October 2022, the Fed raised the target rate to about 3%, which is probably a relatively neutral level, reflecting the success of their earlier work. By then, inflation was over, so there was no need for a hawkish position. But, the Fed has continued to raise the target rate to 5%, which will be deflationary/recessionary if it remains in place too long.

High Mortgage Rates Slowed Down Credit Demand

“In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice, they are not.”

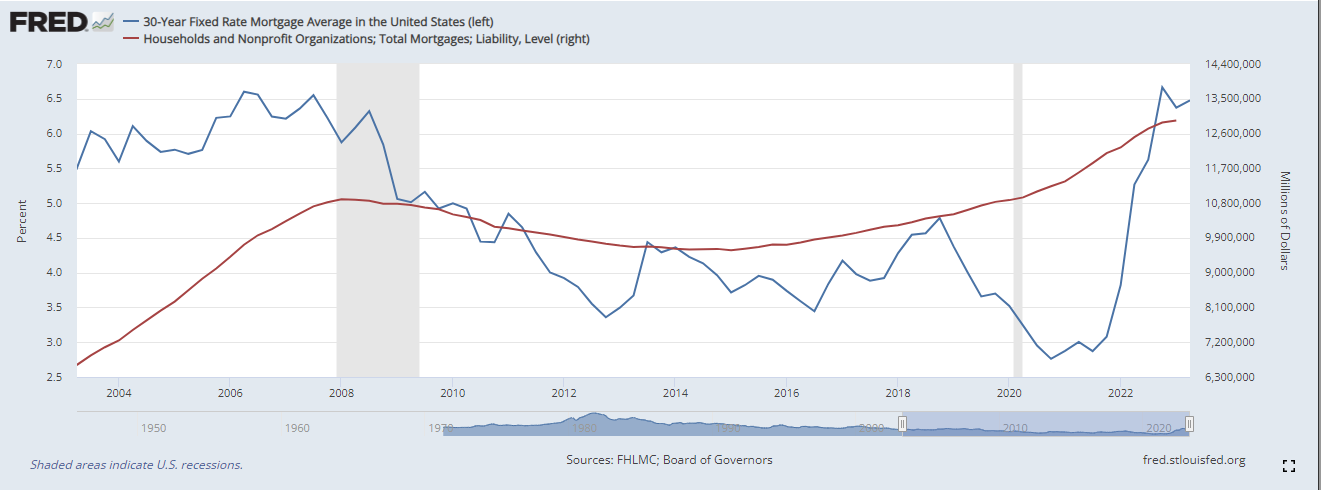

When your theory makes enough sense, the data doesn’t matter unless it confirms your theory, so I’m sure you’ll see a lot more of Figure 4 if mortgage growth does finally start to slow to rates lower than pre-Covid trends later this year.

Higher Rates Lead to Lower Asset Prices, Which Lowers Demand and Inflation

At least the timing fits here. Home prices did flatten out at about the same time as general inflation. Since long term interest rates did increase as inflation expectations recovered, the subsequent end of the temporary inflation did happen after some of the long term rate increases.

On bonds, this is mathematical. Bond values decline when yields rise. So, there is no question that rising long term rates lead to asset value losses for bond holders. (Though, of course, those are gains for bond issuers.) But, this is still begging the question, because it assumes that raising the short term target rate causes long term rates to rise. I assert that delaying the rise in the target rate was the cause of rising long term rates. I suppose, in either case, this is attributing the control of inflation to Fed policy decisions. But, obviously, these are very different accounts with different future policy implications.

On housing, prices are actually still higher than they had ever been when mortgages were 3%. They will likely never be that low again. And, again, we are stuck with the conclusions being the the result purely of the presumptions. I am sure that a hawkish position could eventually hold rates high enough for long enough to create recessionary conditions strong enough to push home prices down some more, and then there will be empirical evidence that high rates pushed down home prices. If you use inflation from June 2022 and ignore the bias created by shelter inflation, you might think inflation is still a problem and that is the right path, and if you follow that path, you will decide that you were right. (See 2008.) I think J Pow may be the man to lead us another way.

Also, I have noted in Figure 5 the point at which price/rent ratios (according to Zillow data) peaked. In other words, all of the increase in home values since then (early 2021), have been due to rising rents, not rising price ratios. Mortgage rates should lower price/rent ratios. But, price/rent ratios had leveled out for a long time when mortgage rates were still near 3%. There was a brief burst of housing demand above capacity that pushed up price/rent in late 2020. The last 2 years of home price trends have basically just mimicked general inflation. Mortgage rates aren’t correlated well with any of this.

In Figure 6, I have included an estimate of price/rent ratios using the Case-Shiller price index and the CPI rent estimate. Using that measure, it does look like there was a period of rising price/rent ratios that coincided with low mortgage rates, and which then reversed sharply after mortgage rates increased.

But, that is completely from the lagging effect of the CPI measure of rent inflation. It’s an echo of bad data. It only has value inasmuch as it confirms the normal story of inflation, home prices, and rent. But, it’s basically a data fiction.

Everyone is Wrong About Everything

So, there you have it. Either I am an old curmudgeon who has a knack for twisting data into contrarian stories, or everyone is wrong about everything. Or…

Or, I agree with everyone 80% of the time, but I only write about the disagreements.

I especially like the sentiment, "Everyone is Wrong About Everything."

I do not know how germane this is, but inflation is dead or even deflation in China and Thailand, and getting there in Japan. Most of the world is in disinflation, and pretty strong.

There is this:

Today's CPI Data by Truflation

USA

The USA Inflation Rate by Truflation is 2.34%, -0.23% change over the last day. Read Methodology

https://truflation.com/

Also, why is it a sacrosanct premise that only commercial banks can expand the nation's money supply (due to the fractional reserve banking system, which evolved by happenstance)?

This makes real estate the de facto whipping boy or the exalted prince when it comes to managing monetary policy.

In the pandemic, Bank Indonesia just bought bonds directly from the government, to see that nation through that period. It worked, Indonesia does not have runaway inflation, or a depreciated rupiah, and taxpayers are not leveraged (since the Bank Indonesia is part of the national government. Bank Indonesia can roll over on the bonds in perpetuity).

Stanley Fischer and Ben Bernanke have discussed money-financed fiscal programs.

But the orthodoxy is the US government must borrow, borrow and borrow more...