Supply constraints and residential improvements

The unfortunate popularity of false premises

I recently saw this interesting twitter thread that made some insightful observations, but got sidetracked by the mistaken priors of conventional housing wisdom.

Here is the basic setup:

Decades of savings are in the average American's home, and mere renovations are now major investments on the scale of what houses once were

It wasn't always like this. And It won't be much longer…

The Victorians massively overbuilt housing and they overbuilt the individual houses.

Multiple depressions and world wars destroyed the fortunes needed to build and keep these beauties.

Maintaining & heating them would bankrupt a person post-war. They had no market value.Thus even as these gorgeous treasures sat rotting ordinary Americans were ordering kit homes out of the sears catalogue to be delivered by rail and assembled on empty lots.

Once your house isn't an asset, every additional square foot is just more expense.

What they are basically describing is the most important facet of amply supplied housing - filtering. Existing homes filter down to households with lower incomes, and so you can own a home which was a symbol of wealth and status for your grandparents simply by being willing to maintain it. There were depreciated, affordable homes just sitting there, begging to be used.

One of the insights that my price/income framework has really hammered home for me is that filtering is everything. And, the writer here is really onto a subtle point. Those homes weren’t affordable because they were depreciated. They were depreciated because they were affordable.

This subtle point is a key element in the highly counterintuitive notion I have been developing that the most important outcome of generous mortgage lending is that it keeps rents low for the families that never get a mortgage. The effect is so strong that when we introduced a massive discontinuity in mortgage access in 2008, it inevitably led to a market where even the prices of the formerly funded homes were higher than they had been with generous lending. Making it easier to buy those kit homes from Sears meant that old Victorian homes were worth less than it would cost to replace them, or sometimes even to maintain them. That was because they had low rental values.

That is how prices in our mortgage deprived neighborhoods have been able to rise above the relative price levels they were at before mortgages were suppressed. That is because older homes were mostly selling at a discount to replacement back then.

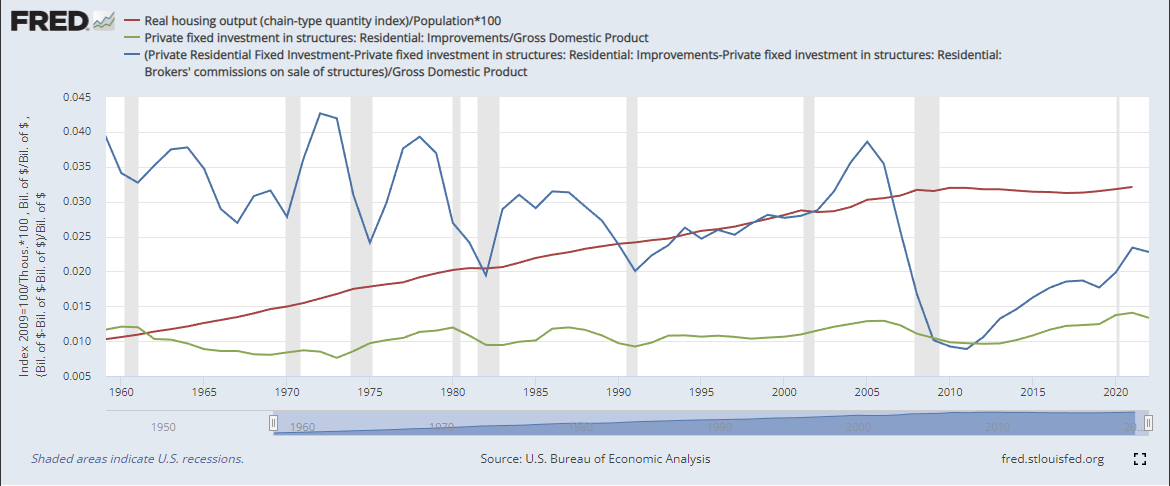

The writer is correct that more residential investment goes into improvements today than it used to. Until the financial crisis, 20% of residential investment, give or take, went into improvements. Since the financial crisis, it has stayed over 30%.

Of course it is. If it is difficult to make new homes, of course capital will flow into existing homes. That capital isn’t the cause of rising values. It is the result of them.

Here’s where it goes off the rails:

There is very good reason to think this process is already starting again.

Foreign money pouring into western real estate is already drying up thanks to the closing of China and Russia.

but the real story is (say it with me) demographics…

All debt driven assets will probably collapse in price.

The thread’s conclusion is that high interest rates, low population growth, demographic trends, and declining immigration will inevitably lead to a housing crash. Home values have been inflated by foreign capital, easy credit, low interest rates, population pressures, etc., and when those pressures recede, look out below.

This is a bit of an odd, but common, turn. The descriptive part of the thread recognizes the importance of supply, but even there, they come up with an alternative hypothesis about why those houses were allowed to depreciate. That hypothesis is a bit incoherent to me. We were too poor after the wars to maintain the old homes, but not too poor to build new ones? They seem to imply that the old homes were too big or nice, and that was why they couldn’t be maintained. It’s reminiscent of the explanation I have sometimes heard of how even LA had a housing construction bust after 2007 even though they clearly weren’t oversupplied. The story is that builders overbuilt $800,000 homes when what LA needed was $200,000 homes.

These stories don’t ring true to me. Sunk costs are such a large part of the cost of a home that the potential downward price discovery of existing homes is large enough to find a buyer in all but the most extreme circumstances. This is basically how mid-20th century housing was so affordable.

It’s a shame that these alternative explanations are so easily accepted. We don’t need alternative explanations.

The explanations for the coming bust are also odd. If foreign capital, low interest rates, and demographic-driven demand have been responsible for the recent inflated home prices, then why has residential investment and real expenditures on housing been so oddly low? This isn’t a marginal point. Those are really weird things to focus on given the broad trends of housing markets over the past couple of decades. Those are conclusions that come from an overdeveloped sense of axiomatic financial relationships. They certainly don’t arise from empirical experience.

It’s such a strange aspect of housing finance discourse. It’s not like these demand-side infatuations consistently arise from misinterpreting this type of underlying data. Mostly, the writers simply don’t engage with it. And, they are right not to, inasmuch as their readers don’t ask for it. High prices driven by low interest rates, foreign capital, etc., aren’t so much a conclusion as they are an axiom. And, there is no more effective way to go off the rails than starting with inaccurate axioms.

While it is true that improvements have jumped up as a percentage of all residential investment, it isn’t as true of improvements as a percentage of GDP (green line in Figure 2). There has been some increase in improvements/GDP, but most of the increase in improvements/residential investment came from the deep drop in the denominator - non-improvement residential investment (blue line). And, that shift (higher improvement spending and lower residential investment) coincided with a sharp and unprecedented flattening in real per capital expenditures on housing (iow: rental value adjusted for inflation - red line).

Clearly, over-fueled demand for buying or building homes isn’t the primary motivator of our time. And, clearly, we are more than capable of throttling housing production enough to keep prices high in spite of lower demand trends. The reason we got this natural experiment in housing underinvestment is because we have spent 15 years applying our inaccurate axioms in practice.

All that being said, at the end of the day, home prices are determined by supply and demand, so it is still possible that declining demand from the reasons noted could lower demand enough to reverse high prices, even if those prices were largely driven higher by supply constraints when demand was higher.

On that, let me make one final point. Figure 3 shows the price/income levels for every ZIP code in Austin in 2005, 2012, and 2022 and in LA in 2005 & 2022. From 2010 to 2020, population in the LA metro area was basically flat. In Austin, it increased by about 2.5% annually, and population in Austin from 1995 to 2005 had increased by about 3% annually.

So, let’s say there is a massive downshift in housing demand and US population, or at least household growth, is flat for the next several decades. Until recently, it had grown by around 1% annually for some time. So, all else equal, Austin will have, say 1.5% annual population growth. Maybe that will return it to 2005 or 2012 price/income levels. But going from 3% to 2.5% didn’t.

What about LA? Its population growth will be whatever it allows it to be. From 1995 to 2005 it was just under 1% annually. We can already see what effect 1% lower population growth rate can have in LA.

Every city’s price/income chart should look something like Austin in 2012. The way to get there - the only way to get there - is building. Until we fix that, nothing - interest rates, foreign capital, pandemics, demographics - is going to lower demand so much that we can’t continue the self-harm at a scale that outweighs it.

The entire reason for inflated aggregate real estate values in the US is the unusual cost of housing in low-income neighborhoods, and especially, the unusual cost of housing in low-income neighborhoods in places like LA. Low interest rates, population growth, and foreign capital have nothing to do with the difference between a poor neighborhood in LA and a rich one in Austin. The first step to thinking about the future of American housing is giving up on your inaccurate axioms.

All that said, @FromKulak is absolutely correct to note that one thing to look for to know when we have enough is when there are beautiful old homes that you can make your own with a little sweat equity. Unfortunately, that isn’t going to happen by accident. It took a lot of political work to make it go away to begin with.

I should be working right now, but I get riled up whenever somebody starts predicting a price collapse in housing. I'm grateful that you corrected the conclusions that @FromKulak draws about the broken filtering system in older housing stock. The current situation is exacerbated by decisions that homebuyers make when seeking out good school districts. Communities with poor schools tend to have cheaper homes which generates a clear signal to first-time homebuyers to avoid looking for housing there. Parents will sacrifice housing quality for better school districts, and in a supply constrained environment it makes the rent/income slope worse.

So, it is possible to have a "price collapse" in communities with demographic changes, but if there are massive supply constraints in a region that tends to reinforce a flight to quality to more expensive neighborhoods with better schools. I've been seeing this effect in rural areas of New Hampshire and some towns around Boston--places that probably fall outside your data sets. It should also be noted that the "price collapse" often isn't enough to properly filter the quality of older homes in a way that benefits bargain hunters who aren't in a rat race for good schools.