Previously, I made the case that, under our current housing conditions, rent should be excluded from price indexes that inform monetary policy.

In addition to the more permanent riddles that rent inflation creates, there are temporary problems related to methodology. In this unusual transitory episode where CPI inflation rose sharply and then suddenly ended, literally at once in July 2022, lags in the way that rent inflation is recognized in the consumer price index have created a number of pitfalls for economic analysis.

In previous posts, I have argued that general inflation explains rent inflation and rent inflation explains home price inflation. In other words, there is nothing to see here in housing costs. Inflation in general experienced a sharp one time jump. Relative to general inflation, rent has just kept charging ahead, a couple percentage points higher annually than general inflation, driven by persistent underbuilding.

Figure 1 compares the Zillow estimate of changing rents, the CPI excluding shelter, and the shelter component of CPI. You can see that the shelter component of CPI is just a lagged shadow of general inflation. There hasn’t really been much unusual movement in timely rent inflation since the Covid disruption. The unusual movement is mostly just the lag in the CPI measure. Including rent inflation (shelter) in the cpi just adds bias and noise.

Comparing rent inflation derived from Zillow’s estimated rent measure to CPI inflation (excluding shelter), there have been a couple blips and bloops, but basically, rent inflation has moved steadily along a path of about 2% excess growth annually since 2015, adding up to about 20% cumulatively.

When there is excess rent inflation, there is even more excess home price inflation. Aggregate home prices have just moved up along with excess rents as they always have. Again, with a couple minor blips and bloops along the way.

This is broadly misunderstood. Below I will discuss one way in which these misunderstandings lead housing analysts astray and one way in which it might be leading to mistaken macroeconomic inferences.

Housing supply and Rent

It has become conventional to report that a wave of new housing has sharply reversed rent inflation.

At its worst, this analysis simply references nominal rents, and attributes the drop from 14% rent appreciation to 4% rent appreciation (or lower depending on the measure cited) entirely to supply dynamics.

It is more accurate to say that the decline has been entirely due to general price trends and so there is literally nothing here.

A somewhat more sophisticated approach is to adjust rent inflation with general inflation. But rent inflation has basically followed general inflation. If you compare rent inflation with general CPI inflation that includes the CPI shelter component, you’re actually mostly comparing rent inflation to the bias created by the mismeasured rent inflation in the CPI!

Look at figure 1. Timely measured rent inflation is about as far above CPI inflation that excludes shelter today as it normally is. But total CPI that includes shelter is still biased higher because the CPI shelter component still includes some inflation that really happened a year or 2 ago.

So, analysis that attempts to adjust rents from some non-CPI source using the full CPI inflation measure is just measuring actual rent inflation against a measurement error in rent inflation. It’s comparing the black line in Figure 1 to the gray line. An ironically meaningless number.

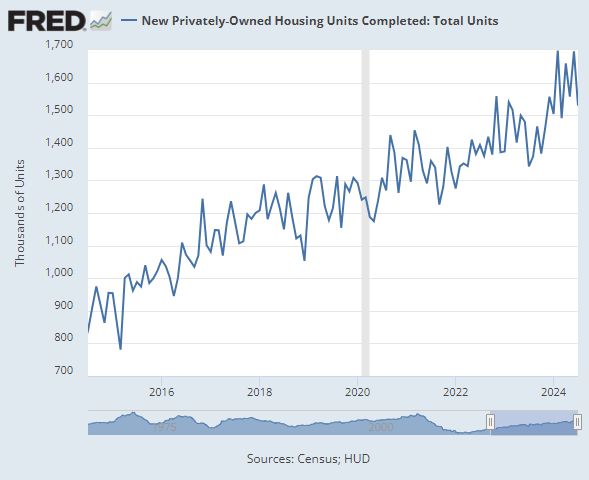

The other oddity here is that there has not been a wave of new housing supply. New housing has been coming online in a remarkably linear trend since the bottom of the Great Recession. Figure 3 shows total completions.

If you squint hard, you might be able to see a hundred thousand more units in the last year than the 2022 trend would have led to. That’s a growth in the housing stock of about 0.1%.

If that could have brought down rent inflation by even 2%, then let’s start collecting pennies and nickels. We really can solve housing affordability.

At the personal level, your investments probably aren’t going to do well if you proceed as if a wave of supply just wiped out rent inflation. And YIMBY public outreach will probably suffer if it is based on the same.

Wage Growth

Wage growth is another area affected by this.

The Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker is a handy tool for analyzing wages. They track several different wage measures. If you don’t adjust wages for inflation (black line in Figure 4) then it looks like there was a surge in wages that has gradually weakened.

If you adjust for inflation, then the rise in wages actually only partially countered inflationary losses. Real wage growth was flat in 2021.

Nominal wage growth looks like it spiked up and then slowly retreated. Real wage growth looks like it spiked down and then slowly recovered.

I am, of course, a JPow! stan, so I forgive the overshoot. But if you wanted to use hindsight to judge monetary policy, you could argue that in 2022, the Fed should have generated 3-4% inflation to keep nominal wage growth steady at 3-4%. Instead the Fed created 6-7% inflation (according to the aggregate CPI). That was 3% more than necessary, in theory.

But, here again, the CPI index includes rent inflation which has been recently mismeasured.

Figure 5 compares wage growth adjusted with aggregate CPI and wage growth adjusted with CPI that excludes shelter.

There are two points of interest here.

First, as I argued in the previous post about excluding rent from monetary analysis, rising rents aren’t really inflation. They aren’t payment for the production of anything. They don’t affect the use of labor or capital. They are simply a transfer to landlords for owning a portion of the fixed supply of land. They are more akin to a gift or a theft than they are to a payment for production.

Looking at it this way, the difference between the blue line and the orange line in Figure 5 is basically the amount of growth that is being siphoned from productive Americans by rent-seekers.

It’s a tremendous cumulative transfer. It is also highly regressive. Rent inflation has been much higher for poorer Americans than for richer Americans. A more targeted inflation estimate that accounts for the regressiveness of rent inflation would basically show no wage growth for Americans who earn relatively low wages over the last decade.

But recent cyclical trends have a brighter story to tell. Adjusting wage growth with CPI excluding shelter to remove the methodological lags, wage growth looks much more regular. Wage growth went negative in 2021 and 2022. But then it recovered sharply. By this measure, real wages (before rents) have been very regularly returning to 2-3% growth with quite strong reversion.

Looking at it this way, wages came right back up to that norm and have remained there. In fact, since the recovery from Covid, real wage growth (before rents) has moved up to a 3% growth norm not really seen since the late 1990s.

This suggests that we are on a stable glide path with strong real growth that is sustainable.

Just an aside...Dollar General and Dollar Tree and the other dollar stores are reporting weak results.

Can't say, "Oh, that is because of rents," but given Erdmann's work on rising rents to income in lower-income zips...and the lack of new construction....after-rent incomes might be stressed in the dollar store crowd.

"This suggests that we are on a stable glide path with strong real growth that is sustainable."--KE

With all the soul-draining news out there, I will grasp onto this like a drowning man grabs onto flotsam.

The negative Norm in me says that in housing-constrained cities, the real wage growth will disappear into housing rents...and so is not so real.

BTW, I agree the Fed has been roughly right since C19 hit. And that hindsight is perfect. Being roughly right in real time is a solid success story.

I still wonder about the fact we live in a globalized economy, money is a fungible commodity, and there are other major global central banks following their monetary policies.

So...is monetary policy made globally in a multi-polar world?