Quick Review for Funsies

I was recently sent this tweet, which seems like a good jumping off point for a quick overview of the housing market:

The first 2 points here are reasonable. Home buying and selling activity are affected by nominal mortgage rates in at least 2 ways. First, when rates are high, they increase the cash outlays required on a conventional mortgage, and so they present a capital constraint for some portion of cash flow-constrained buyers. Second, they create a friction on activity because the odd American norms around mortgage lending mean that when you buy a house with a conventional (fixed rate) mortgage, you are bundling a real asset with a nominal liability that you can’t trade at market value. So, if your bank wants to sell your 3% mortgage to an investor, they will have to take 70 cents on the dollar for it, but if you want to pre-pay it (in effect buying it back from the bank yourself), you have to pay full face value. This is an odd discontinuity which creates friction that affects buying and selling activity.

However, there is a difference between gross buying and selling activity and net demand or intrinsic market values. Figure 1 compares trends in mortgage originations, total mortgages outstanding, and mortgage rates. There is a noticeable parallel movement since 2019 of declining then rising mortgage rates coinciding with rising then declining gross originations. However, there is basically no correlation between mortgage rates and net changes in mortgages outstanding. (Actually, even in gross terms, the amount of new originated mortgages in the third quarter of 2022 was still higher than in any of the quarters from 2009 to late 2019, when 30 year mortgage rates were between 3% and 5%.)

So, I think the difficult thing to keep in mind is that mortgage rates probably do matter a lot in some contexts for gross activity, but most of that rate-sensitive activity is related to trading and liquidity. The difficulty, it seems to me, is that we see that activity. We experience it. It seems like an important fact we can hang our hats on. And, it just isn’t. It just doesn’t net out to anything significant. It’s a bit surprising, the extent to which it is unimportant. Yet, the numbers are the numbers.

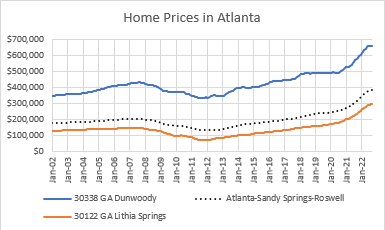

To think about the third point, let’s follow the home price trends in a couple of typical Atlanta ZIP codes.

As shown in Figure 2, home prices in Atlanta are up something like 50% on average, since the beginning of 2021. Two representative ZIP codes are also shown here. The richer ZIP code is up a little less than the poorer ZIP code in percentage terms, but trends are similar. It seems reasonable, at first glance, to expect at least a 20% pullback, and this rise did happen to follow a period of low mortgage rates.

Figure 3 shows the same ZIP codes in terms of price/income. This helps to highlight differences between the ZIP codes and real changes over time. This presents a bit of a different picture. Prices are up a bit in the rich ZIP code since 2020, but the price/income ratio has basically just recovered from a recessionary low point back to a pretty typical moderate level. The poor ZIP code hit a low back in 2011 and has been on an upward trajectory since, accelerating in 2021.

Now, I suppose you could incorporate my credit shock thesis and say that the credit shock knocked 50% off the median property value in the poor ZIP code. Then, low interest rates for the following decade caused prices in poor ZIP codes to rise to new highs. In other words, there could be a one-time permanent access discount, and after accounting for that, you might be able to attribute rising prices in the poorer ZIP code to low rates - even if investors are the ones that must act on them.

Figure 4 compares rent inflation between those two ZIP codes. Is there a hypothesis for how low interest rates would only affect home values in the poor ZIP codes where the tenants can’t get mortgages, and at the same time low interest rates would cause rents to rise only in those poor ZIP codes?

And, looking at price/rent ratios, the rich ZIP code again is relatively level over time. The price/rent ratio in the poor ZIP code has recently risen quite a bit, from the low teens to the mid-teens over the past few years. So at least part of the recent appreciation is from rent inflation, but the question remains whether the rise in the price/rent ratio is due to low rates or to high rents and constrained supply.

I have a hypothesis for this. When you make it harder for tenants to get mortgages, construction declines and rents increase (especially where incomes are low). Eventually, price/rent ratios rise on low-end properties as more of their value comes from supply obstructions and land values. And, eventually, prices rise high enough to induce construction of apartments and new homes for rent, filling in the gap left by the hobbled owner-occupier mortgage market. If that market is allowed to expand, it might finally end the rising rents.

And, really, considering that, after 2007, we blocked demand for mortgages for millions of previously active borrowers, isn’t it probable that some of the decline in mortgage rates since then is due to suppressed demand? Many people simply don’t account for this, and it leads them to (imho) a distorted viewpoint, where for a decade they treated evidence of financial suppression (low rates from a lack of “qualified” borrowers” and a lack of construction activity) as if it was evidence of financial stimulus (low rates from Fed money printing). The temporary boost of inflation after Covid is creating a false sense of confirmation for that view (just as the tight lending regulations after 2007 created a false sense of confirmation for the “housing bubble” view), and that view appears to have become widespread enough to provide brave and cocksure investors like you and me with buying opportunities on assets priced for a construction bust.

Even though these peculiar relative shifts in rents and valuations have been larger than any factors that I am aware of in American housing markets for decades preceding the Great Recession, they seem to still be mostly unappreciated, and the first question I would ask anyone asserting some coming generalized crash in home prices would be any question that tests whether they have considered these various divergences (trends of rich vs. poor metropolitan areas, rich vs. poor ZIP codes, etc.). If they have not, then they are working with a veritable bingo card of Rumsfeldian pitfalls (things you know you know, things you know you don’t know, things you don’t know you don’t know, etc.).