Lance Lambert recently shared these comments from Fed Governor Michelle Bowman. Her broad point in the speech was to support further rate cuts, in light of signs of softening labor markets. Of course, I am a JPow! stan, and I think he gets too much criticism for targeting both low interest rates in 2021 and high interest rates today. I think it would be hard to find a better policy path than the one he has managed to follow, all things considered. But, a reasonable case can be made, on the margin, for a slightly lower rate target today. So, I don’t take issue with Bowman’s broader speech.

Here, I want to focus on her comments on housing. Apologies in advance. I’m going to be a cranky contrarian. Her comments will be bold, in block quotes.

Declines in housing activity, including single-family home construction and sales, have been accompanied by higher inventories of homes for sale and falling house prices, suggesting that housing demand has also weakened.

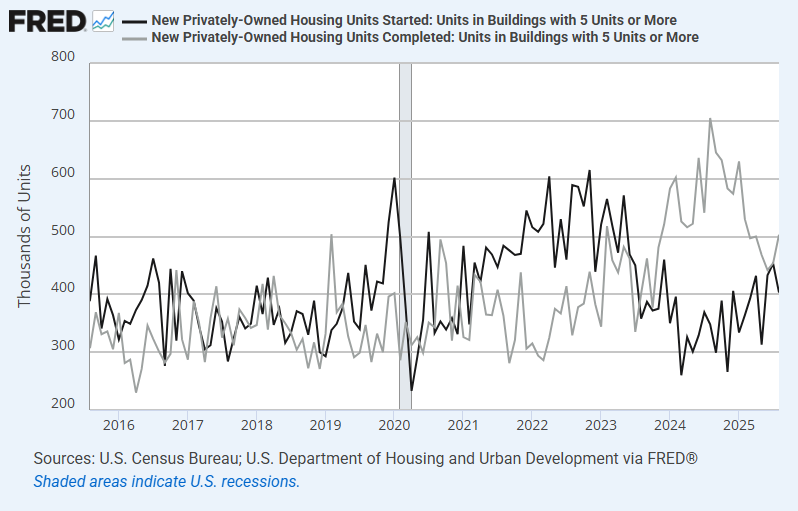

Are the declines in housing activity in the room with us now? Residential investment has been flat as a pancake. Multi-family starts got a temporary boost after Covid hit, and two years later those starts turned into completions. But, in the time since that temporary boost played out, starts stabilized. There is no sign of decline.

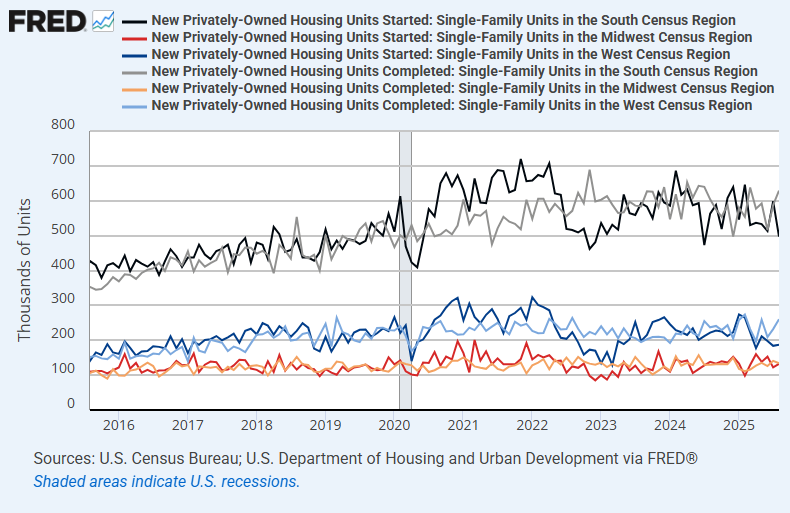

There is no sign of decline in single-family construction either. There have, of course, been slowing sales in parts of Florida and Texas, reported by the builders. Not enough to show up in any regional Census data. If you squint, you can point to a decline in starts in the West and South over the past 6 months, though in both cases the estimates are still within the range of horizontal noise.

Builders have announced modest reductions in starts, but in the aggregate, they are still hitting supply constraints and selling completed homes quickly.

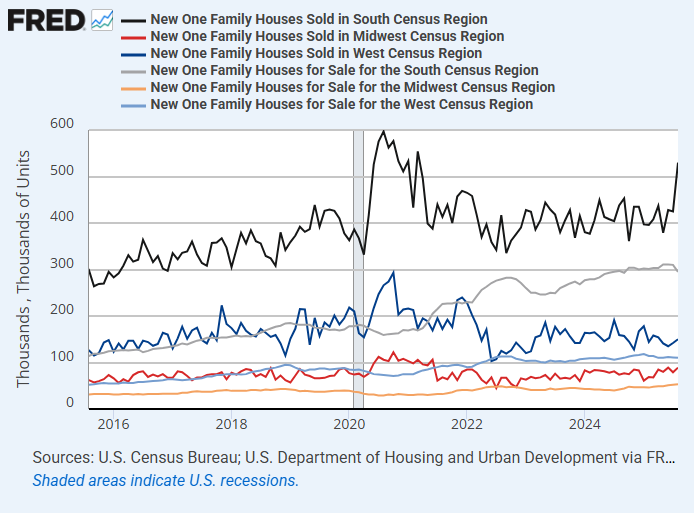

No sign of decline in sales or unusual increases in inventory for sale either. In the raw numbers, there has been a persistent increase in new units for sale, but there hasn’t been a recent uptick, and Erdmann Housing Tracker subscribers understand that inventory of units for sale is, if anything, a bit low.

Demand has declined a bit. Builder revenues have tended to be slightly negative, due to compositional shifts to smaller homes, a slight reversal of Covid era input costs, and margins normalizing from Covid highs. None of that would call for stimulus.

There are some signs of economic weakness. But under the conditions of a shortage, housing is now a defensive sector. Weakness isn’t going to show up here. This is a change from the past and an opportunity to profit from understanding that change.

Elevated mortgage rates may be exerting a more persistent drag as income growth expectations have declined while house prices remain high relative to rents.

Mortgage rates are at least as much an effect as they are a cause. Treating them as a cause creates a lot of trouble. When the Fed raised its target rate from 2004 to 2006 and then held it there, they made this mistake. Then, they believed that the fact that long-term interest rates didn’t rise along with the Fed Funds Rate was stimulative. In fact, long-term yields remained low because the Fed had already created recessionary conditions by 2006, and the housing shortage hid how recessionary conditions were by providing households in struggling cities with billions of dollars of home equity to draw on.

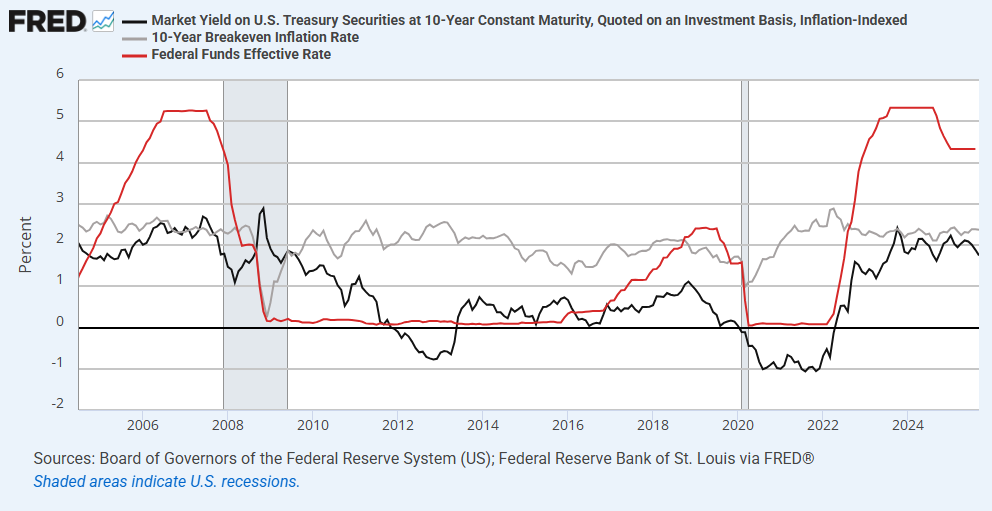

Figure 4 shows the Fed Funds Rate and 10-year Treasury yields, disaggregated into the real yield (black) and the inflation component (gray). As a general rule, when the cyclically neutral target rate is volatile and the Fed is behind it, chasing it, short and long-term rates move in the same direction. When changes in the Fed rate are causal, short and long-term rates don’t move together.

In 2008 and 2019, the Fed was chasing a falling market rate. In 2022, the Fed was chasing a rising market rate. In 2005 and 2006, the Fed was pushing above the neutral market rate, so long-term rates didn’t rise. In 2024, the Fed pushed a bit below the neutral rate, so long-term rates didn’t decline.

Mortgage rates are high because demand is still strong relative to supply. The only way mortgage rates will decline significantly from here is if the Fed errs by keeping the target rate too high or if Trump’s chaotic policy choices lead to a decline in investment. Lower rates aren’t going to be a part of any return to affordability. They will be associated with a slowdown in income expectations. And, we are in a shortage condition, so housing costs are not particularly sensitive to incomes.

Given very low housing affordability, existing home sales have remained depressed since 2023 and at levels only comparable with the early 2010s following the financial crisis.

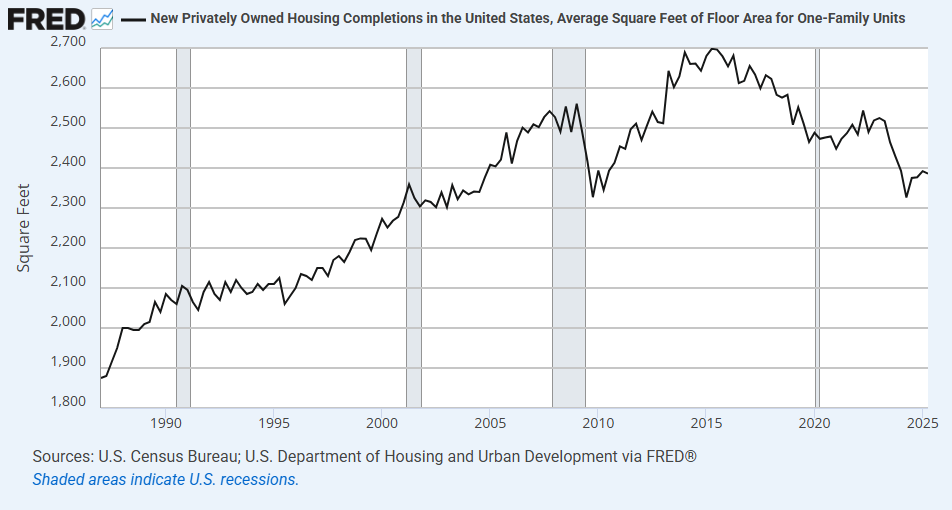

There is a kernel of truth here. If you define housing affordability as mortgage costs, then higher mortgage rates have lowered transaction volume among families in existing homes. This has little bearing on production or prices of new homes. There has been some marginal shift of credit constrained borrowers buying smaller units. But, as with everything else, there is too much focus on the role of mortgage rates. The average size of new homes has been declining since 2015. Changes related to interest rates in 2020-2023 were just a blip on that path.

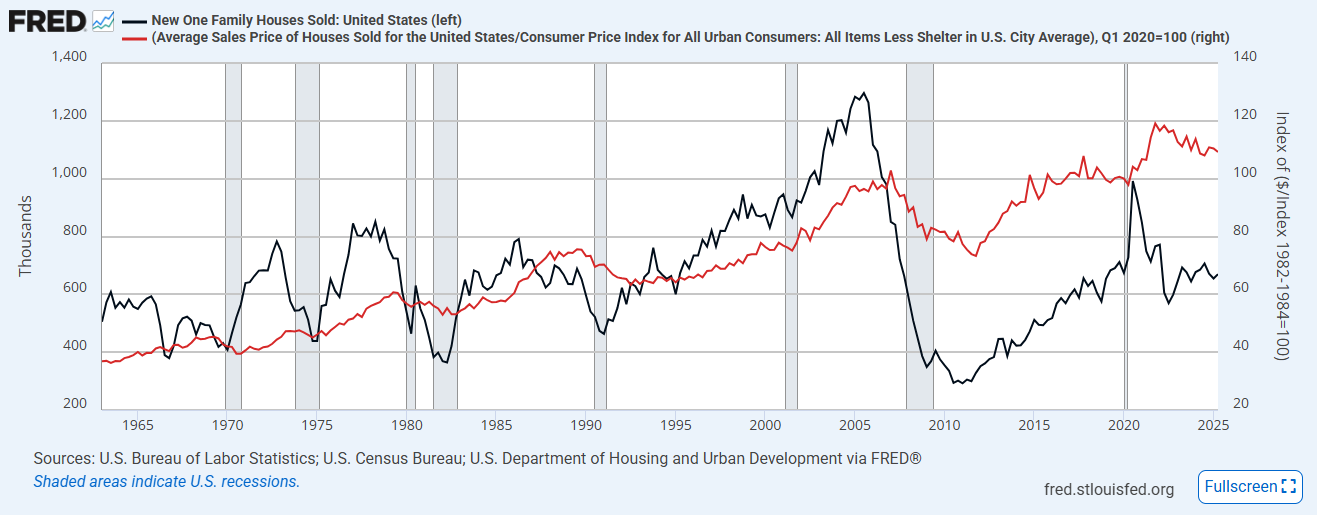

As with interest rates, I think it’s weird how the norm in American real estate discourse is to treat affordability as a causal factor. Prices are an effect, not a cause. I suppose you could say that changing supply conditions change affordability in a way that affects the quantity of homes demanded. But, that is a slow-twitch factor. That’s why the red line (real prices) in Figure 6 tilts up over a 40 year period. That has nothing to do with the business cycle. Higher prices are clearly cyclically associated with more activity.

I think it’s sort of bizarre that so many analysts and policymakers seem to hallucinate a trend that never happens. I suppose it looks like worsening affordability in 2021 caused sales to crater. But that is wrong. The builders didn’t have any houses to sell and they didn’t have the capacity to make more. Sales cratered and prices spiked because supply conditions changed suddenly. That’s not going to happen in the other direction.

Now, I do happen to think that, if it is allowed to, the new housing market will continue to grow, and that will lead to better affordability. So, rising activity will be associated with moderating prices. We will be lucky if that process can play out in less than 20 years.

I am concerned that, in the current environment, declines in house prices could accelerate, posing downside risks to housing valuations, construction, and inflation.

In a shortage condition, the only thing that can cause nominal home prices to accelerate down is a deep credit shock, like the one we created in 2008. We can’t do that again. There is no way that housing prices can do more than moderate.

Of course, that isn’t true locally. Big shifts in population flows can cause price shifts in local markets. That means prices have dropped in some Florida markets, and they have risen in the Midwest and Northeast markets where Florida newcomers generally come from. National prices are relatively flat and will remain so.

Let’s hope that these misperceptions are widespread enough to motivate counterparties to take the other side of our profitable trades but not so widespread that they affect JPow!’s stellar decision-making in the short time we will still have him. I don’t look forward to losing him.

What do they smoke at these Fed meetings? The only positive thing I can derive from Bowman's commentary is that she is identifying the potential for weakness in the housing market, even if it's for the wrong reasons.

"In a shortage condition, the only thing that can cause nominal home prices to accelerate down is a deep credit shock, like the one we created in 2008." Good point!