More ResiDay 2025

Mortgage Access, Build to Rent, and Bill Pulte

In an earlier post, I reviewed my interview at ResiDay earlier this month. Here, I will review some of the other presentations. You can see videos of several presentations at ResiClub’s YouTube channel. I will limit my comments here to the presentations that touched the most on common topics I address here at the Erdmann Housing Tracker.

Sean Dobson, CEO of Amherst

Sean Dobson, the CEO of Amherst, was one of the speakers at ResiDay. Currently, there isn’t a video posted of Sean’s presentation, but Lance Lambert, the head of ResiClub & ResiDay, has posted a pre-event interview that touches on several of the same themes.

Sean is a singular voice and a singular operator in the housing market. He has led Amherst successfully through it all. They were in the mortgage securitization business and managed to survive 2008 and then pivot to large scale investments in rental housing after 2008. He’s the GOAT.

While I have come to center the 2008 mortgage crackdown as the major force pushing housing markets into odd trends from a 30,000 foot analytical view, Dobson has come to that view from the trenches. Here is a single leader who can answer all the questions from the inside. He would rather facilitate mortgages for his tenants to be homeowners than be their landlord, but the current regulatory regime makes that impossible.

Amherst is interesting in several respects. They are constructing their own new rental homes. They are also focusing a lot on infill developments and small, individual renovations with added density. They seem to be working on an interesting strategy where they develop modular building methods that they apply to individual scattered site updates to make infill and renovation housing more competitive compared to greenfield tract home construction.

I recommend viewing the video above. In his appearance at ResiDay, he made some additional comments about lending and the rental market.

He spoke about his interactions with policymakers. They ask how to address the housing crisis, and eventually, he has to get to the nub of the problem and tell them to loosen up lending standards. Then they go radio silent. The moral panic in 2008 was just so entangling, it will take generations to get out from under it. Correcting from the mortgage crackdown is still a non-starter. Sean Dobson says, on principle,*Take my customers away. Give them access to mortgages.* and nothing can move the needle politically.

Congress is more likely to go the other direction and take away Amherst’s customers by blocking new investment in rentals, without providing an alternative. As Dobson put it, “When they say I shouldn’t own these houses, they never talk about my customers.”

He also delivers another talking point Erdmann Housing Tracker readers will recognize. The problems with the lending boom before 2008 were related to fraud and small scale speculators. The mortgage crackdown removed access to mortgages of honest homeowners with moderate credit scores. Those families had nothing to do with the parts of the pre-2008 market that were toxic.

Another point he made was “Going from a 740 to a 640 credit score takes 2 missed payments… Getting back to 740 takes 5 years.” Amherst has very good financial relationships and payment metrics with these families. He considers them good credit risks. Their average income is above $100,000, yet they typically can’t get approved for mortgages. Additionally, he noted that single mothers are a significant customer group for Amherst because their credit score may have taken a hit because of the divorce process, even though they are good credit risks.

My impression is that a web of bureaucracy, mandates, and spread caps have been laid over mortgage underwriting in a way that removes discretion from the underwriting process, even for banks holding loans on their own books and taking the risk.

If there are qualified borrowers not getting mortgages, why isn’t someone stepping in to take that market? Ask Sean Dobson, because Amherst can be the landlord or they can facilitate those mortgages, and he tells Congresspeople to allow those mortgages to happen so that he loses his qualified rental customers, because that would be best for his customers and best for the country. They won’t do it.

Jim Jacobi, CEO of Parkland Communities

Jim Jacobi was another interesting speaker. Parkland is in the build-to-rent business. Jacobi noted that they have found detached single family neighborhoods to be difficult, and they are focusing on various forms of attached homes like townhomes.

He expects build-to-rent of several different housing types to continue to grow. He noted that many municipalities are already putting up obstacles to rental neighborhoods, even these neighborhoods that generally take the form of single-family residences rather than apartment buildings.

Parkland is focusing on an interesting townhome model where the exterior of the units looks like a luxury townhome with a two car garage, but it is really sort of a stacked duplex. In the townhomes are 2 units, each 3 stories tall. A really interesting design. One advantage of it is that each unit has a staircase which is positioned at the shared wall. Two staircases block the sound between units that tends to be a problem in apartments, so the units are much more private than a normal duplex or apartment.

This product is an answer to the inflated urban land values that I write about here - the scarcity premium that inflates all lots across a given metropolitan area uniformly. By stretching the units vertically with typology that looks like a dense single-family form with minimal private lot space, they can get zoning approval while lowering land costs.

Jacobi said, “A lot of people think build-to-rent is taking opportunity away from homeownership, and I completely disagree with that… If somebody wants to buy a house, they’re gonna go buy a house… My biggest competition is apartments. But, meanwhile, I love apartments. I’d rather my community be right in the middle of 5 apartment complexes because I’m gonna take their residents because we have a better quality product.”

This is a product built for our time. It minimizes land costs without all the building code and zoning obstructions intended to prevent apartments. And, this is the sort of missing middle housing that can create community within growing cities. There are zoning issues, but it is easier to get variances to residential typologies that aren’t apartments. These units will be less sensitive to the declining land values and land rents that I am tracking with my metro area data packages than detached single family neighborhoods will be. Or, put a different way, if the premium on urban land is basically “bribing the land” for the right to a house in a market that has a shortage of homes, then getting variances to get a right to more homes on a given plot of land without moving all the way to a multi-family unit type that attracts opposition will provide alpha to the builder.

Parkland has been buying land aggressively. Jacobi sees developers being tepid about lot development and sees opportunity to step in. This also meets the EHT seal of approval.

Some pundits insist that the American housing market is dominated by suburban single family housing because that is the type of housing Americans prefer. But, here is Parkland, basically trying to thread the needle with “missing middle” housing that creates marginally higher density within existing urban space, and Jim Jacobi will tell you that their binding constraint is getting legal permission to do it. Preferences aren’t limiting the growth of this product. City politics are. Jacobi also notes that this product is much less expensive than traditional apartment buildings, and you can be sure that most of that difference is due to building code impositions that were explicitly motivated to prevent cities from building affordable housing types. I guess these obstructions to various housing forms reflect someone’s preferences, but definitely not the preferences of the tenants who live in them.

Dennis Bron, Chief Growth Officer of Roofstock

Roofstock provides transaction and property management services for single family investors. Dennis Bron reported that activity had been slow for the past couple of years but that investor activity is heating back up.

He noted that with the growth in single-family rental activity, interest in the sector, and developments in trading and management of the assets, the asset class has the advantage of flexible exits. A unit can be rented to a series of tenants, sold to another investor, sold to a homeowner, etc. This provides an advantage over commercial real estate investments.

He sees a lot of pent up demand from the investor side with funds underallocated to real estate relative to their targets, so he sees a bit of a floor on real estate activity.

From his viewpoint, changes in yields lead to changes in investor interest, which is certainly a correct way to describe this. I suspect, though, that the causation might be from a different direction. In the before times, when housing was demand driven, investor and homebuyer interest would wax and wane over the course of an economic cycle, and the number of units completed would rise and fall substantially as they did.

Under shortage conditions, housing completions, and thus household formation, is limited by the slowly rising capacity level of new construction, which is currently about 1.6 million new homes annually and rising by about 100,000 each year.

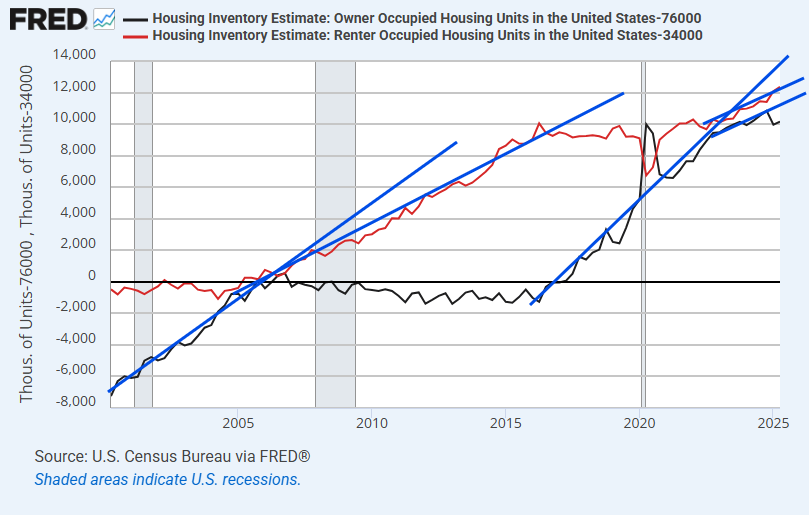

Figure 1 highlights one way to look at this. In the 2000s, there was a boom in homeownership. All new households, on net, were owners. This was historically odd. It was a combination of things like the credit boom, demographics, and migration to areas where homeownership was more accessible.

Then, the housing market broke and the mortgage market broke. Until 2016, construction of new homes was very low and household formation was low. Now, all the new households were renters. Then, that flipped again from 2016 to 2022. Some of that was just an end to the tremendous shock to homeownership that was imposed in 2008. Eventually, households on the margin were going to buy homes again, if at a somewhat lower rate than before 2008.

The growth of owner households after 2015 was actually pretty similar to the pre-2008 rate. Possibly there was some recovery of households re-entering ownership as they recovered from post-2008 foreclosures. The extremely positive affordability when home prices and mortgage rates were both low might also have goosed homeownership. But, the main deviation during that period from historical norms was the lack of new rental households. Adults per home was climbing and rent inflation was high. The number of owner households was growing. Household formation was being limited by the number of homes, and the margin that had to give was renter household formation.

After 2022, homeowner growth slowed. Was it worse affordability conditions? Probably in part. Maybe the post-2008 recovery in homeownership among some households temporarily harmed after 2008 had played out by 2022, lowering the rate of new homeowners to a more sustainable trend. That was associated with a similar increase in renter households.

My point here is that there are millions of households waiting to form. Homeowners are the drivers of the housing market. If there are 1.6 million new homes this year and 1.6 million new homebuyers, there will not be any new renters, on net. If there are 1.8 million new homes and 1 million new homebuyers, there will be 800,000 new renters. Homebuyer activity is the cause (inversely) of investor activity. In the past, homebuyer activity changed the number of completions. Today, there is pent up demand and construction is at capacity, so homebuyer activity reduces investor activity.

Now, of course, the way that plays out is that homebuyers will bid up prices and bid down yields when they outnumber new home completions, and so it is true that along that causal chain, yields are what, operationally, will pull or push investors into or out of the market. But, I think it really is a derivative of how many homes are claimed by homeowners under a supply constraint. New home completions will continue along a relatively linear path. The only question is what portion will be purchased by owners vs investors.

In the past couple of years, apartment completions have accommodated the additional renters. Apartment completions have settled back down a bit now, so more of the rental market will be met through single-family. Bron sees that as higher yields attracting investors. I’m saying, that’s not wrong, but I am suggesting a different way to think about that causally in the upside-down world of a supply constrained market.

Bron also made a point about the downsides of the long-term fixed-rate mortgage. His point was that it advantages older homeowners over young first-time homebuyers. I think this relates to my occasional point that fixed rate mortgages front-load the cash outflows. He also noted that the fixed rate ends up keeping families in homes that are not necessarily appropriate for them because moving would force them to refinance to higher rates.

Fixed rate mortgages basically bundle homeownership with a speculative position on future inflation and interest rates. It’s really pointless that we have created a housing market where decisions about tenancy are randomly associated with past trends in inflation.

Bron would prefer mortgages with shorter fixed amortization schedules, which would generally lower mortgage payments and also would put the mortgage rate of a family that has been in a house for a decade or so at the current market rate, and remove these random arbitrage issues from their housing decisions.

At the Mercatus Center, I proposed a form of mortgage that would address some of these problems.

Jaime Arouh, LendingOne

Jaime Arouh with LendingOne had some interesting comments. Maybe, for me this is just confirmation bias, but I appreciated his comment that interest rates aren’t that important of a driver of investor activity in build to rent. There are a lot of moving numbers, and it is just one number on one part of a capital arrangement. (Connecting this observation to the discussion above, other margins like building costs, land costs, and rent levels and trends play a part in the relative yields Bron discussed.)

His forecast was for some cooling in build-to-rent activity, but for it to remain well above any pre-Covid activity levels. I expect more growth, but in either case, the baseline expectation is that this sector is here to stay and will be growing as a portion of the stock of existing homes as units are completed each year. That will happen even if interest rates remain much higher than they were before 2021.

He also noted that some of the hot build-to-rent markets are, in his terms, “oversupplied”, and he noted that some attention is turning to markets in places like the Midwest.

I think this is basically the insider’s way of describing the building boom I predicted in the previous post on my interview at ResiDay. The fast growing markets are getting near a rate of construction that is starting to moderate rent inflation. To a developer, that will look overbuilt. But, this is a supply constrained market. We are in a disequilibrium. The rate of supply will need to be above sustainable for some time for pent up household formation to occur to get back to an equilibrium market.

Trends in construction, rents, and prices will not be following along an evolving equilibrium path. They will be moving from a disequilibrium with elevated land values back toward an equilibrium where the scarcity portion of land values is bid away. There will be an interesting balancing act there in terms of the pace new product developers are willing to complete versus the pace of moderating rents. Moderating rents will feel like oversupply during this process. It will be oversupply. But, it will be oversupply back to equilibrium, not away from one.

This will be an interesting time.

An interesting aspect of that will be the evolution of land prices over time and the willingness of land developers to engage with the market. I’m not sure I fully know how that will work, but it will trend back toward equilibrium.

In the meantime, I am pleased to hear confirmation from someone on the ground working on these deals that some interest is turning to the Midwest. Land values have still been too low in many Midwest markets, or have just recently recovered to levels that might be associated with a recovery in construction - finally. Lacking new construction, rents have continued to rise in the Midwest while they have moderated in the faster growing markets with more construction. I suspect there is market share for the taking in some Midwest markets that have not yet developed an active build-to-rent marketplace.

Bill Pulte, Head of FHFA

Bill Pulte did a virtual interview, and he made several new announcements that have been reported in the press. After the ResiDay event, Pulte announced plans to introduce a 50 year mortgage product at Fannie and Freddie. It has met with much criticism. I was going to go into that a bit here, but this post is already long enough. Long story short, I think the product would be fine. If it helps create more options for buyers, I have no problem with it. The criticisms against it are wrong or overwrought. But, on the other hand, if the objective is lowering the initial payment for first-time home buyers, it’s not a very effective mechanism for that. I doubt that it will be used much. Also, see Dennis Bron’s comments above about fixed rate mortgages.

At the ResiDay event, Pulte claimed that builders are sitting on inventory. Erdmann Housing Tracker subscribers know that’s wrong. I try to save these observations for subscribers, but completed homes are selling faster than they ever did in decades of data before 2021 and some builders are still having a hard time completing new units or opening new communities as quickly as they would like to. They are supply constrained. Full stop. Different builders have different approaches to inventory management in various localities that have temporary idiosyncratic softness in sales, but certainly a number of builders are choosing to let margins slide a little in order to keep the pace of sales up, even given the difficult supply conditions.

The inventory of finished homes is definitely very high, but it isn’t high compared to the rate at which they are selling. This is a subtle problem and a common mistake made by real estate pundits.

Pulte suggested that he will look into strongarming builders to change pricing and production.

He, of course, complained a lot about Jerome Powell. Pulte doesn’t understand how interest rates or monetary policy works.

He then announced that Fannie and Freddie would be taking equity positions in homebuilders. He claimed that homebuilders were offering Fannie and Freddie equity because Fannie and Freddie “hold all the cards”. Is there a single producer or consumer who would want this? The Trump administration recently announced that it would reverse tariffs on things not produced in the US, like bananas. Are we sure we don’t produce bananas? We really seem like a place that would produce bananas.

Finally, he said that Fannie and Freddie would remain under conservatorship. They plan to issue shares in an IPO to private investors, but it will only be a small percentage of the total equity, which is mostly controlled by the federal government now.

This is interesting. Generally, among conservatives, getting Fannie and Freddie out of government control has been a long-term goal. I think the agencies have been falsely maligned. There are many theoretical problems with such public control of mortgage access, but as long as federal regulators impose even tighter regulatory controls on private mortgage lenders, what exactly is the distinction? And, the agencies were the best behaved and best performing conduits for mortgage access during the 2000s subprime boom and bust. Their market share was extremely countercyclical, for instance.

So, I am happy to hear that they will remain under conservatorship, though it is surprising to see that plan coming from a Republican administration.

I think the general point of view regarding the original semi-privatization of Fannie and Freddie in the 1970s is that it was an attempt to get the associated debt off the federal government’s books, even though the government’s continued guarantee of their losses meant that they had responsibility for the debt anyway, now with added moral hazard. In other words, it was accounting hocus-pocus that caused more problems than it solved.

Pulte seems to view this more as an exchange of cash flows for capital, like it’s some sort of deal that is accomplishing something. There is no public reason for it, that I can think of. Private investors will require a higher return on investment than the Treasury does, so the capital injection the government receives will be worth less to the government than the cash flows it is selling off.

But, this was definitely the most positive announcement Pulte made. It will be mostly meaningless and will mostly continue the status quo. There are major changes I would make to the status quo, but with Pulte and Trump in charge, the status quo is a relief to the senses. I’ll take it.

It’s a shame. It seems like there is room for improvement here. Pulte appears to be looking for ways to make mortgages and homes more accessible. Here we have the GOAT Sean Dobson at the same event (though they were not in a position to meet and discuss, since Pulte was virtual) explaining that the problem is underwriting. Essentially, to a certain extent, Pulte has a button on his desk that he could push to make internal technical changes to underwriting process at the agencies. He could push for changes in the Ability to Repay rule and other regulatory overlays that reduce underwriters’ discretion.

Is Pulte aware of this? Could he be made aware of it? Would he be able to manage a change like that, which would need to be implemented with some care?

On the one hand, he seems like the kind of FHFA director that is looking for radical change to boost the housing market. On the other hand…

I have a subscription to this stodgy, British magazine that comes weekly and covers a broad range of topics. They recently ran a piece on how mortgage access needs to be improved in this country--citing the dearth of loans to midfield credit scores as a hangover of policies from the Great Recession. Amazing stuff.

So, one of my points of contention is that you seem to think that defending build-to-rent is the hill we need to die on in order to even start climbing our way out of the crisis.

Is this an accurate characterization? I’m trying to be fair here, since you’re a pretty honest interlocutor.

But in general, it feels like that particular hill is not the one we need to die on. Rather, it’s the previous ones - legalizing SRO, stuff like that.