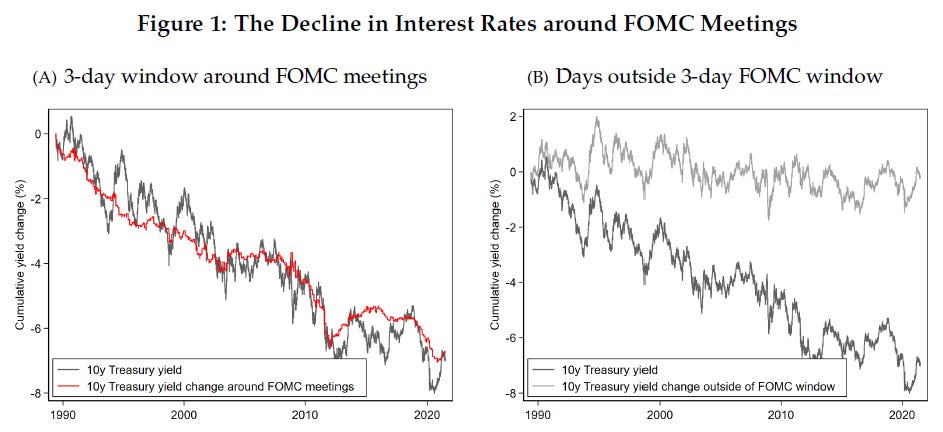

The other day, I reviewed a working paper about the effect of Fed decisions on long term interest rates. Figure 1 is the key visual from the paper. It differentiates rate changes between those that happen around Fed meetings and those that happen outside Fed meetings. The red line in the left panel is the cumulative rate changes that happen around Fed meetings. I see it shared from time to time as evidence that the Fed, through rate control, communication, and revealed knowledge, controls trends in both short term and long term interest rates.

I am skeptical, because the parallel movement over time between aggregate changes in interest rates and changes that happen around Fed meetings is the result of a relatively uniform downward trend. Without any big shared idiosyncratic shifts in trends, it is hard to know whether these trends are related or whether they are both affected by some other factor.

I theorized that if there is a small risk premium that uniformly cycles around Fed meetings, it could create this pattern even though almost all of the important rate changes happen outside of Fed meetings. I detrended all three measures and updated the data to reflect recent events, which have included the sharp shift in rate trends that could confirm or contradict the relationship. And, when I did that, in Figure 2, all of the recent changes in interest rates have happened outside of Fed meetings, confirming that the correlated downward slope of the left panel of Figure 1 is likely spurious. Changes in long-term interest rates are probably not correlated with new information from Fed meetings.

The main effect the Fed appears to have on interest rates is just that they might really screw things up at each meeting, so investors require a little extra real bonus yield to hold bonds before a Fed meeting. That causes the downward slope in cumulative rate changes around Fed meetings, which will likely continue regardless of the trend in long-term rates.

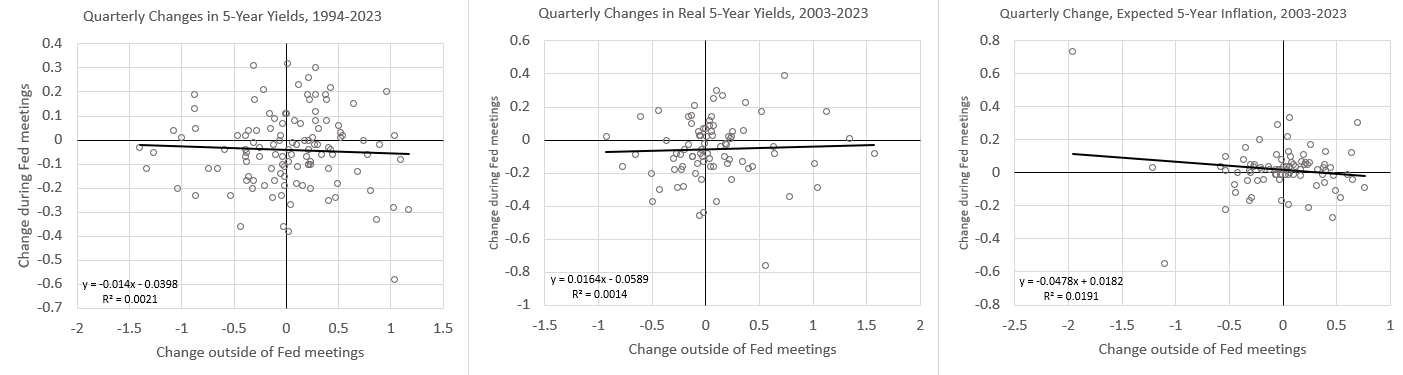

To further check into these relationships, I looked at quarterly changes in interest rates, rather than the cumulative change. How much of the change during each quarter happened during Fed meetings vs. outside of Fed meetings?

Total quarterly change is on the x-axis. The change that happened in each category is on the y-axis. Fed meetings in orange, outside Fed meetings in blue. Nominal yields in left panel, real yields in middle, inflation expectations at right.

Figure 3 shows 10 year yields. Days around Fed meetings are about 10% of the trading days, and they account for about 10% of trading changes. (By construction, the sum of the 2 slopes is 1.) Disaggregating between real rates and inflation expectations, changes in real long-term rates do have a somewhat larger magnitude around Fed meetings. Inflation expectations have a somewhat smaller magnitude.

Figure 4 shows 5 year yields. Similar results. In all cases, the results are regular. The relationship is linear. Real quarterly yields in both cases tend to decline slightly during Fed meetings and rise outside of Fed meetings, uniformly. (In the middle panels, the orange regression line crosses the y-axis below zero and the blue line crosses above zero.)

One issue here is that Fed communication is ongoing. Fed members frequently signal changes in sentiment in public comments between meetings, for instance. As anyone who uses the FedWatch tool at the CME knows, the market guesses about Fed decisions constantly. Frequently, expectations of a rate change will probabilistically change between meetings, with just the last little bit of uncertainty resolved when the announcement is made.

So, it could be that the Fed is controlling changes in rates, rate expectations, and inflation expectations throughout each quarter, moving them in the direction that will be decided at the meeting. So, I looked at the correlations between rate changes that happen during Fed announcements and outside Fed announcements. If they are correlated, then signals about future interest rate trends might be coming from the Fed, but most of the communication and rate changes would happen outside of the meetings.

Figure 5 shows changes outside Fed meetings on the x-axis and changes during Fed meetings on the y-axis for 10 year yields. Nominal yields in the left panel, real in the middle, and inflation on the right. Figure 6 shows quarterly changes in 5 year yields.

And, yikes, do I have news for you. There is zilch. Not any correlation at all. Not in the 10-year. Not in the 5-year. Not in real rates. Not in inflation expectations. Not a messy correlation. Not a bit of something, but weak. Nothing. Nada. Honestly, this surprised me a bit.

Changes in long-term interest rates happen almost entirely outside Fed meetings, and they are completely independent of changes that happen during the meetings.

I suppose you could conclude that the Fed communicates so well that their policy decisions are completely accounted for even before they start each meeting. But, this still doesn’t bode well for the story that Figure 1 was supposedly telling.

Also, here again, you can see that the regression line crosses the y-axis below zero. The one statistically significant outcome here is that rates tend to decline slightly around Fed meetings. (The intercept is negative.)

In a market that is trading based on the notion that the Fed has driven mortgage rates higher, and that this sort of lever is their normal tool for cyclical monetary policy management, I will gladly be the counterparty to that trade.

Well....

I dunno. Yes, any particular Fed meeting might not cause interest rates to jump much, for all the reasons you suspect.

But if mortgage lenders (commercial banks) charge higher interest rates, that will tend to depress construction and property-sale transactions.

M2 growth largely happens when commercial banks finance property deals. (Most loans require collateral, and that is property). Commercial banks (fractional reserves in action) print money and lend it out to property buyers, who give it to property sellers.

Who gets the new money (M2)? The sellers of real estate, and maybe construction companies.

Lately, this picture may have changed, with QE. Now, some argue (I think I agree) that new money can enter the economic system directly, through QE aka money-financed fiscal programs.

That is, the federal government is financing outlays by having the Fed buy US Treasuries bonds, with printed (digitized) money. Michael Woodford says this is the case, and I am just a wag, so I will agree.

For me, the question is, "Why would the Fed ever sell its bonds?" and, "The Bank of Japan has financed half of that nation's huge national debt. 50% about, and Japan national debt somewhere about 240% of GDP. They have only mild inflation, and usually deflation. Why not copy Japan?"

Obviously interest rates also respond to other factors, such as inflation, flight-to-safety, capital gluts, and so on. Maybe even perceived opportunity costs.

----

There is another question that if we have globalized capital markets (we do), and money is fungible, then maybe you need the bulk of the world's major central banks working in the same direction....

It also might be this topic is too complicated to understand....