I recently posted a piece on the trade deficit. I wrote in generalities there and broad estimates. I suppose I should have included a little more data.

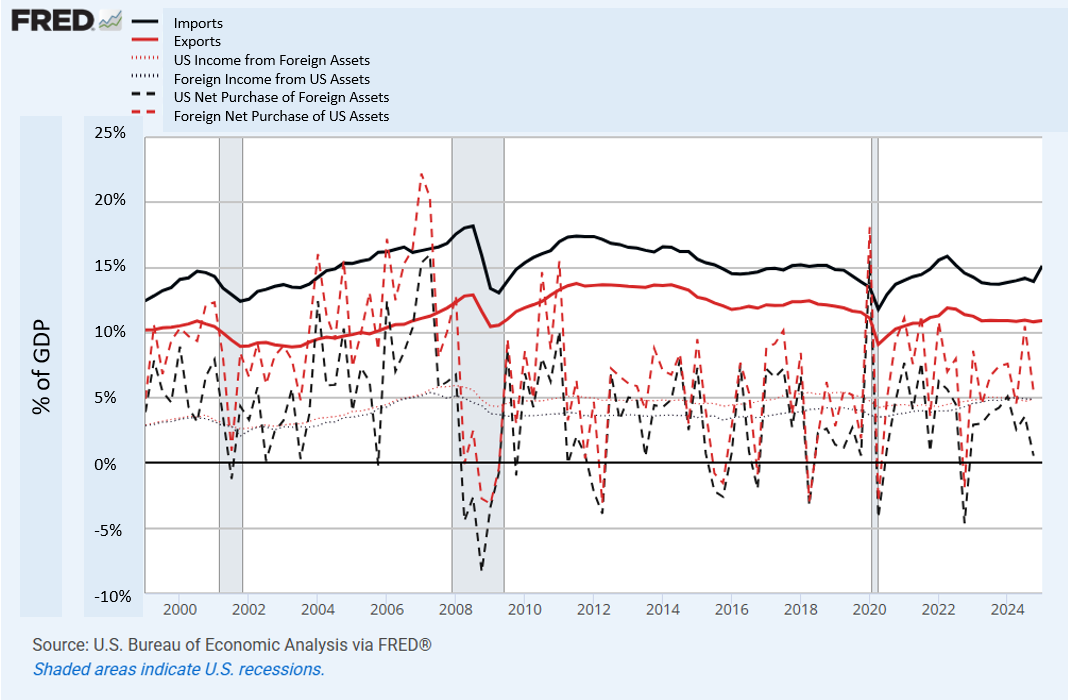

Figure 1 here shows imports and exports (solid lines), income from foreign assets (thin dotted lines), and new international investments (dashed lines), all as a percentage of GDP.

You can see that the international income tends to be pretty balanced. We run a persistent trade deficit and capital flow surplus.

The capital flows are little noisy, so in Figure 2, I compare the net trade and capital flows.

The trade deficit and capital flows are mirrors of each other. Cash comes in to buy American assets or to lend to the American government or corporations and we use a lot of that cash to buy extra imports.

If this was about profligacy or if it was unsustainable in any way, then those thin dotted lines in Figure 1 would diverge. Foreigners would increasingly earn greater profits on their growing American investments. Over time, that would cause the dollar to depreciate. And, if that was happening, the trade deficit would naturally decline.

The reason this is sustainable is because Americans make higher returns on our foreign investments than foreigners make on their American investments.

So, this isn’t a story of profligacy or living beyond our means. But, could it still be a story of selling out American workers by moving production abroad? American capitalists move factories to low wage economies and buy imports with their greedy profits while American workers are left high and dry?

No. Again, thinking about what is happening here, this isn’t being driven by off-shoring. American investors are investing less in foreign assets than foreigners are investing in the US. If the trade deficit was being driven by offshoring, wouldn’t the increase in imports be related to more investments into foreign assets rather than more foreign investments into America?

The idea that low wages are what causes production to move abroad is, itself, a confusion. I have written about this before. This is sort of a similar issue to the way that homebuilders tend to attribute high housing costs to high construction costs. To a CFO looking at a spreadsheet, it’s straightforward. If you raise the interest rate on the spreadsheet, it makes a project less viable. To a CFO looking at moving a factory, if you raise the wage expense, the factory is less viable.

For the CFO, it probably doesn’t matter much if this leads to a mistaken understanding of the macroeconomics of trade. Costs are costs. You don’t necessarily need to understand what’s driving them. Most executives probably believe that production moves to where wages are lower.

The confusion comes from “all else held equal” thinking. All of those costs are part of an interconnected web of interactions. Interest rates may be high because investors are looking for risk more than safety and more corporations are seeking debt financing for expansion plans. So, at the micro level, high interest rates seem like they work against profitable activity, but at the macro level, they are frequently associated with more activity.

Likewise with wages. High wages are the product of the quality of local economic and public institutions. They are a product of the broad set of alternatives that workers have access to. They are a result of the productivity that comes from the incomprehensible web of cooperative and competitive actions and opportunities that are present in an economically advanced community.

Production moves to places where productivity is rising and institutions are improving. Production moves to places that find themselves capable of producing more. Production moves to where wages are rising, not where wages are low. Production appears to move to where wages are low because the places with the most potential for improvement are the places that were previously worse off.

Of course there are frictions and inefficiencies in economic activity, and sometimes they create temporary stresses like unemployment. But, except for temporary imperfections and frictions, generally almost every worker in the world is working on something. It’s not like there were millions of Asians just sitting around with nothing to do, and then we moved some factories there, and now they are working while the former American workers are now sitting around with nothing to do.

Production moves to where wages are rising, not where wages are low.

Millions of Asians have been increasingly capable of producing more, and they were going to produce more. Nothing could stop them. We could have committed to our own descent into future relative poverty by refusing to benefit from commerce with increasingly productive economies. But, that would have required increasingly tight control over what Americans could buy or produce. There is no functional alternative where nobody loses 1970s era jobs and the economy remains functional.

The reason some production moved to places like Asia is because the opportunities for Asians to produce things more productively were growing. And the reason wages for workers in America were higher than wages where those factories moved to is because American workers had and have more opportunities to be productive than the Asian workers did.

In fact, if wages in America were higher than the wages where the factory moved to, you could say that the reason some production moved overseas was because American workers have opportunities to perform more valuable work. Wages are derivative of an economy’s potential. If Americans didn’t have better alternatives, then American wages wouldn’t have been so high.

Now, it may be the case that some regions had optimized to the competitive advantages they held in specific industries, and the transition to the new economy is especially difficult there. It may be the case that frictions in the American economy are too high. For instance, it might be harder to move to cities with more economic opportunities than it should be because of the housing shortage. Maybe that has reduced the web of interconnected opportunities that keep wages high, and has reduced our potential to trade off lower value production for higher value production. But, that’s hardly the fault of foreign economies who allow us to benefit from their improvement. That’s just a case of us choosing to be poorer by limiting the extent of our potential productive economic activity.

If you just look at a list of American trading partners, it is clear that the amount that we import is largely associated with physical proximity and with high wages. The higher the wages, the more we import. We import much more from Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam, and China than we did when their wages were much lower.

Imports increase from places with rising wages, not from places with low wages. In the counterfactuals where less production would have moved abroad from the US, current American wages would be lower, Americans would be less productive, and Americans would have fewer economic opportunities. These are the two sides of a coin of a basic economic rule of thumb. Economic growth comes from getting rid of jobs, not protecting the ones we have.

That means we should strive for a balance of an economy with vibrancy and a generous level of public support for individuals that get caught up in the frictions of change.

Unfortunately, even in the best, most generously managed economies, there will always be objections to economic progress. That’s what objections to lower costs are. Objecting to lower costs is not the road to broadly shared prosperity. Neither is refusing to accept the increasing consumer surplus offered to us by other nations who have managed to overcome the unfortunate human intuition against it. It’s a rare win in history, and still not universal across the globe today. Take the win. Nurse the growing pains. But take the win. There is no better way.

There’s a great musical called “Hadestown” with a scene at the end of the first act that has a call and response between Hades and his working slaves called “Why We Build the Wall”. I’m not sure the show’s authors would agree with what I have written above. But, with the elegance allowed by poetry, the song, to my ear, is a portrayal of the misguided human intuition to guard our “lump of labor”.

Perhaps its the capital flows that drive the deficit and not the reverse...

Coincidentally, I’m pretty sure today’s post from Noah Smith is making much of the same point as you are. Great minds think alike!