In the previous post, I mentioned that the US was actually the oddity in 2008. Most of the world either always had relatively moderate home prices (Germany, Japan, etc.) or home prices increased in the years leading up to 2008, and then they just kept going up (Australia, Canada, etc.). So, since the earliest reviews of the crisis, those who sought to blame it on global phenomena would point to Spain and Ireland, which were the rare cases that paralleled the US. It was a global housing bubble because in the US, Spain, and Ireland, prices jumped up and then collapsed back down. That’s a bubble. And, since there was more than one country, it was global.

I have not studied Spain closely, but it seems like there could have been some sort of unsustainable speculative bubble there. Of course, the US was not, for the most part.

Here, I will compare the US, Australia, and Ireland. Basically, the US and Ireland should have looked like Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the handful of other countries that have seen an increase in home values over the last few decades. They generally are Anglosphere countries.

The US and Ireland look like they had housing bubbles, in hindsight, because they engineered housing busts. But, there was no reason for the busts. And, it would have been much more typical for them to not have had housing busts.

In many ways, Ireland looks like an extreme version of the US, or, more specifically, it looks like Florida and Arizona would have looked if they were stand-alone countries.

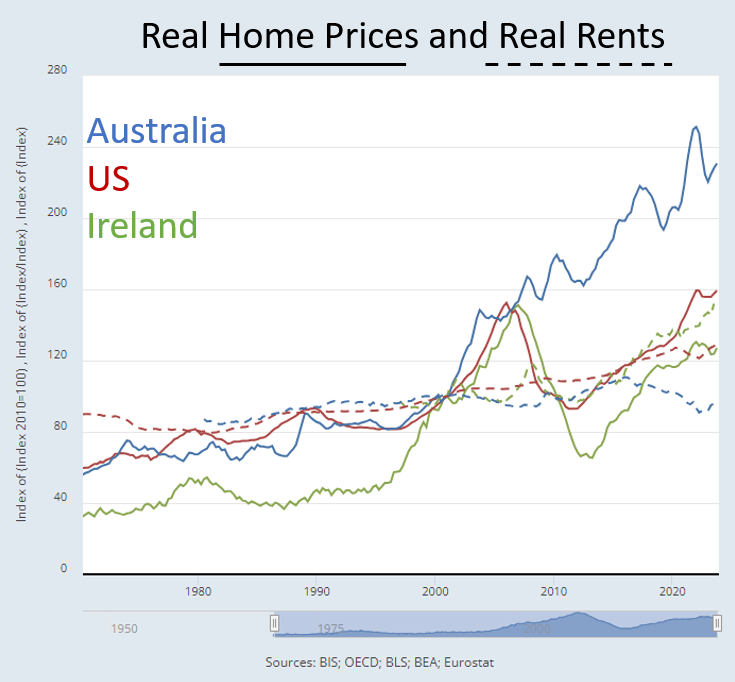

First, Figure 1 compares home prices over time (the solid lines). Basically, there was a deep collapse in home values in the US and Ireland from 2008 to about 2011, and then after that collapse, they continued along the Australia growth path, at the new lower level. In the US, that was triggered by a deep shift in mortgage underwriting regulations. I think Ireland succumbed to the same types of policy choices.

The dashed lines are rents over time. The post-2008 period lines up across these three countries the same way it lines up across the US. Where prices declined the most, rents subsequently increased the most. That is because the price collapse was caused by obstructing funding for home buyers, who are an important source of housing supply.

In Australia, where they didn’t impose that shock on themselves, rents have generally moved sideways, after adjusting for general inflation. In America, as I frequently discuss here, rent inflation has accelerated since 2008. And, in Ireland, it has accelerated even more.

You might notice that prices in Ireland also increased more than they did in the US and Australia before 2008. As I mentioned, Ireland is like the Contagion cities in the US. Ireland had been growing briskly. Figure 2 compares population growth in these three countries.

Just like Arizona and Florida, Ireland had a spike in population growth and immigration. And, just like in Arizona and Florida, it quickly stopped.

Figure 3 compares GDP growth per capita. On top of population growth, Ireland had been catching up to other developed countries. Its income growth had also been rising sharply.

Like Arizona and Florida, Ireland was building a lot of homes because Ireland needed a lot of homes. Fundamentally, there was a spike in demand for shelter. Any speculative activity was secondary to that and motivated by inelastic supply conditions.

You can really see that in Figure 4. Construction employment shot up in Ireland. Then, it collapsed, permanently. Again, looking like the more extreme examples of the boom and bust among American cities.

Construction employment in the US followed along with Australia until 2007. In Australia, construction employment has continued along at the 2007 level, to this day. Meanwhile, in the US, economists were writing articles about how unsustainable construction employment had masked the weaknesses in our economy.

The banks took a beating in Ireland. And the conventional telling of the Irish collapse sounds a lot like the conventional US story, but more concentrated. I’m not sure if the banking collapse in Ireland was more a result of the financial crisis, or if Ireland was similar to the US in implementing increasingly contractionary monetary and housing policies as 2008 unfolded.

I think it is noteworthy that construction employment started to collapse in Ireland at the same time that it did in the US, at the beginning of 2007, well before the financial crisis. By the time of the Lehman bankruptcy in September 2008, construction employment had declined from 16% to 11% of Irish workers.

It seems that, as in the US, the Irish treated that deep employment collapse as a form of normalization rather than a signal of deep instability that should be smoothed or reversed.

Since 2008, Ireland has imposed some of the worst policies that are considered or used locally in the US, and because it is a small nation, they are imposed more thoroughly.

Rent control is widespread.

The future development I am most afraid of in the US is a crackdown on large-scale rental investment. Ireland did it already.

They have a hard limit on borrowing of 4x income for first-time buyers and 3.5x income for others.

Think of the ridiculous situation they have created. There is, effectively, a price cap on owner-occupied homes because of the mortgage rules. That has made the post-2008 shortage permanent, raising market rents. Builders can’t sell homes profitably because the mortgage cap creates a classic shortage, holding home prices below the market value. And as the shortage raises market rents, the gap between the price buyers can pay and the market value of homes widens.

Investors are unwilling to fund new rentals that could bring rents down because rent controls also put a cap on rents. And, for good measure, large scale investors are basically obstructed.

The wait list for public housing runs years long.

Conclusion

It turns out, I’m not the first to notice these similarities to the US. Irish economist Ronan Lyons, at Works in Progress, has written a description of the Irish experience that EHT readers will recognize as very familiar. Lyons describes a consensus that mistook what happened before 2008, leading to policies that mostly made the housing problem worse.

Tyler Cowen recently shared a video from Kieran Lucid describing the problems that have been caused by rent control in Ireland.

Ireland in many ways is the worst case version of the US. Their current housing situation appears to be much worse than ours. And, it appears to be the result of sharing the same demand shock that the US had, but much more deeply. And, then, reacting with more comprehensive and damaging populist responses.

Sure, let's get rid of rent control.

Five years after all property zoning and other restrictions on housing construction are torpedoed.

I am a little taken aback by those who call for one, but not the other, to be removed.

Nice overview. I have a few pieces on Australia's housing cycle under the heading 'the Big Aussie short' https://stephenkirchner.substack.com/p/the-big-aussie-short-at-the-cash