Canton Follow-Up Post

In the previous post, I reacted to a report that Canton, OH, is currently the American city with the highest home rent and price inflation. This should strike anyone analyzing the American housing market through a conventional lens as highly odd. It’s evidentiary example #15,254,305 that we have imposed a drastic, ridiculous supply constraint on American housing through mortgage suppression.

In this post, I’ll cover a few additional points of fact and analysis about Canton to bring home the point, though, if you’ve been reading me a while, you probably know what is coming.

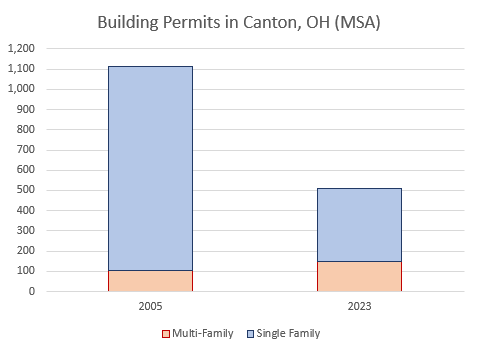

Figure 1 compares housing permits in the Canton metro area in 2005 and in 2023. 90% of new housing in 2005 was single-family. Today, it’s only 71%. More than 100% of the decline in new housing permits was in single-family homes. It dropped from 1,009 permits in 2005 to 361 permits in 2023.

The Zoning Part

If you click on the zoning maps of Canton (pdf) or its partner city Massillon, you’ll find a very typical American situation. It is illegal for 2 families to live in homes that share a wall in something like 85% to 90% of the city. I know this is a very important human rights issue. Thank goodness our cities are looking out for us. I forget if it’s in the Constitution or the Ten Commandments, but I’m sure that in one of those there is something about the scourge of having to drive by homes with shared walls.

Figure 2 shows some typical homes in Massillon. This is an “R-1” street. Single-family detached homes, only. Imagine if the owners of any of these homes subdivided the interiors so that 2 families could live in them instead of one - in a city where rents have risen by 20% more than inflation in the last decade.

We have a social contract, people! The only thing standing between you and urban chaos is the Massillon zoning board.

(I have been told that sometimes my sarcasm is confusing. The 3 paragraphs above are sarcasm. I suppose it does need to be pointed out, because if Massillon did hold a meeting to discuss allowing 2 families to live in these homes, dozens, if not hundreds, of people would sincerely show up or write in to insist that they have been long-time, proud residents of Massillon precisely because the general plan bans 2 families from sharing these homes, and it would be an outrage to renege on such sacred promises.)

The Lending Part

If you poke around the Canton metropolitan area on Zillow, you’ll find that the estimated rent for most homes, especially the most affordable ones, is higher than the estimated mortgage payment, even at today’s rates. For most of the time since 2008, the mortgage payments to buy most homes in Canton would have been a small fraction of the rental payments they fetched.

The residents of Canton didn’t suddenly decide that they liked paying rent and didn’t like ownership. We have blocked them from making obvious decisions. But, more fundamentally, the decisions we were blocking were only so obviously favorable because we had blocked them.

Urbanists and YIMBYs rightly are focused on the largest cities and the challenges they face. So, when the topic comes up about mortgage access and its effect on the construction of single-family homes, naturally, there is a debate about infill construction vs. sprawl. Do we need sprawl? Do we want to encourage it?

But, that debate isn’t particularly relevant to large sections of the country, like Canton. We have discovered, since 2008, that zoning in the Canton area would bind if Canton grew large enough. It wasn’t binding before 2008 because Canton wasn’t growing into a city large enough where the tradeoffs between density and livability become important. It was binding after 2008 because we had a moral panic and made it illegal for most families in Canton to finance the sorts of homes that Canton still needs to build with a stable population.

There has been some realignment in the Canton area. New units in buildings containing 2-4 units has increased from 4 in 2005 to 71 in 2023. Quite a shift. Possibly there has been some regulatory loosening, or maybe the economics of the shortage just made those projects work in the few areas where they are legal. It’s hardly enough to make up for the loss of more than 600 single-family units.

In 2008, we made it illegal for most families in Canton to finance the construction of new homes in Figure 1, and it was already illegal for them to use the existing homes in Figure 2 more intensively. So, rents have risen for the units that exist.

I suspect that we are nearing a tipping point where new single-family homes built to rent are financially feasible because rents are high enough to encourage landlords to build the homes families can’t. That could help Canton become more affordable again. It is possible that YIMBY reforms would release the constraint in Canton through more multi-unit housing. It would be helpful, but not necessary. It would also just be good governance and a nod to the entire functional history of urban human development. Or, looser allowable lending standards similar to any of the decades before the 2010s would turn Canton around, lead to more new housing, and put cash back in the pockets of Canton’s renters.

Cheap<>Bad

The Northeast (every state east and north of Ohio) builds at about the same rate as Canton. In 2005, single-family homes accounted for 62% of permits there. It was down to 39% by 2023.

So, in terms of permits, population growth, and price and rent trends, Canton 2023 is somewhat similar to how the Northeast region of the US was in 2005. Real per capita income growth in Canton has been about the same as in New York City and Boston since 2008. Somebody alert the universities to get to work on those papers about the incredible agglomeration value that Canton has suddenly created.

I have written something along the lines of this paragraph from a recent Atlantic article many times: “Today, America is often described as suffering from a housing crisis, but that’s not quite right. In many parts of the country, housing is cheap and abundant, but good jobs and good schools are scarce. Other areas are rich in opportunities but short on affordable homes.”

I have come to regret accepting a bit of that sentiment in my earlier writing. I think I was wrong. The first phrase of the first sentence in the quote is correct.

Do home price and income trends mean that New York City was a place with good jobs and schools in 2005, and now, since the economic trends are broadly similar, Canton is also a place with good jobs and schools? I don’t think so. I think that is a conclusion that feels empirical but is mostly vibes. I think both cities are just places with a housing crisis. It now infects both New York City and Canton. “Today, America is often described as suffering from a housing crisis.” Correct. Period. Full stop.

This is actually good news. Both sides of the coin were mischaracterized. New York City wasn’t so super, and cheap places weren’t so terrible. Before 2008, there were various regions in the US with various amounts of economic opportunity. Some had less opportunity, and they weren’t growing. Some had more opportunity, and they grew fast. People could move there. They were affordable. There were a lot of places like that.

And, then there was a third group, which also included a range of opportunities among its members. Some had more and some had less. But, they were different than the other cities because they had a housing crisis, so they were expensive.

Then, in 2008, we forced the housing crisis across the country. So, now, there are cities with less opportunity or fewer amenities, and there are cities with more opportunity or more amenities. All of them now have a housing crisis, and they are all expensive.

Why is this good news? It means you don’t have to be a cesspool to be cheap. You just have to make building new housing, on some margin, legal. There are places where opportunity is scarce. Sometimes that’s a hard problem to fix. But, no place needs to be expensive. That’s an easy problem to fix. Just be like cities that existed before 1926 (when the Supreme Court ruled that apartments could be treated as a nuisance, and the age of mobility in the west entered its final act.) You might even say, it’s as easy as being like most American cities before 2008.

What I increasingly find distasteful about that Atlantic sentiment (which, I admit, you could find in some form in both of my own books), is that it makes the United States sound like a real loser-ville. And, it’s just wrong. Like, factually wrong. America would be a place with ample economic opportunities and amenities for all sorts of families in many regions that aren’t expensive. That was true quite recently. We just need houses.

There are struggling places. And struggling places can be cheap. But, today, in the year of our Lord 2025, we have proven: Housing makes you cheap. A lack of housing makes you expensive. Struggling doesn’t make you cheap. Having opportunities doesn’t make you expensive. In 2005, there were many lively and cheap cities in America. In 2023, there are a lot of struggling and expensive cities in America.

Sarcasm? Here? Never would I have suspected.....

The funny thing about zoning as a binding constraint on growth (and eventual affordability) for any urban area is that when property owners use it to induce scarcity they set themselves up for a revolt by a community that realizes that they can upzone in a way that is attractive to developers. Building restrictions and other regulatory factors in the metro Boston area eventually manifested as a development boom in southern New Hampshire that has persisted for several decades. The next frontier for Boston linked businesses and large multi-family is the I-495 beltway. Emily Hamilton's study of Tyson's Corner helps describe this template and it's beneficial impacts.

However, the binding constraint can shift from zoning to transportation infrastructure. If a state or town refuses to improve roads then an outlying community can be effectively abandoned for decades. "You can't get there from here" is a real thing in many parts of New England.

This is a really clear explanation and perspective. Thank you for providing context that I believe can be applied to the organizing for affordable housing that we are doing in Maricopa County.