Agglomeration vs. Scarcity

Tyler Cowen shared a link to a new paper that claimed, “Using a general demand-and-supply framework, we show that our findings imply that constrained housing supply is relatively unimportant in explaining differences in rising house prices among U.S. cities. These results challenge the prevailing view of local housing and labor markets and suggest that easing housing supply constraints may not yield the anticipated improvements in housing affordability.”

There has been a lot of chatter about the paper, so Tyler posted a reaction.

He wrote:

In most circumstances, economists should focus on output, not prices per se. Let’s say we can build more homes, and prices for homes in that area do not fall. That can be a good thing! It is a sign that the homes are of high value, and people have the means to pay for them. It can be a sign that the higher residential density has not boosted crime rates, and so on. I find some of the more left-leaning YIMBY arguments are a bit too focused on distribution. I am happy if more YIMBY leads to a more egalitarian distribution of incomes, but I do not necessarily expect that. Often it leads to more agglomeration and higher wages, and high real estate prices too. The higher output and greater freedom of choice still are good outcomes.

Alex Armlovich from the Niskanen Center expressed a similar sentiment on Twitter:

If the taxable land profit wedge per luxury condo never shrinks no matter how many condos we build, we've got an infinite money pump! I worry how the paper will hold up bc it seems too good to be true Either way: If YIMBYism turns out to be an infinite land money button, you don't go anti-YIMBY—you simply levy a tax on the land & then start pressing the infinite money button!

They both make an excellent point. If more housing in urban centers doesn’t reduce their market price, then housing in urban centers is hugely valuable, and we should build more in any case.

I do think we should build those homes, but I don’t think that is the case. I don’t think it is even plausible. And, contra Tyler, the housing affordability issue is very much about distribution. Not so much the distribution of who is moving or not moving into the expensive cities, but rather who is moving out of them (displaced), living without shelter in them (homeless), or overpaying for the endowment value of home to stay in them (rent stressed).

Building a lot of homes in New York or San Francisco probably will produce a bit of agglomeration value, but it will produce a lot of progressive real income distribution, and the balance isn’t even close. They aren’t expensive because they are super. They are expensive because they are constrained. They are a little bit expensive because they have value for some people, and they are a lot more expensive, and regressively so, because of what they are taking away from some people.

Hoodwinked

Economists have been hoodwinked by their agglomeration models, which are true, but are being misapplied.

The tricky part is that they are true, and they have been saddled with a spurious correlation that overstates their importance.

Over the course of the 20th century, we gave locals far too much power to block city-building. So, every city now is incapable of becoming a city in the traditional sense. The urban development of a few places like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, pre-dates that political development, so they are classic cities with dense urban cores.

It is easy to recognize the practical consequences of agglomeration value. Dense places add value, but they cost more. So, when your class valedictorian moves from the sticks to Manhattan to pursue their career in high finance, they might spend a little bit more than you do with your middle-manager salary in Sticksville, and they might live in a much smaller home than you do, but they get that big high finance salary in exchange.

The result of that is that they consume less housing, spend more on it, but have more left over as a result. Within cities we can see similar tradeoffs. The same rent gets you something very different in Brooklyn than it gets you in Massapequa.

But, generally, everything scales. Incomes are higher and costs are higher, and households trade off some of the luxuries in the basket of services we call “housing” (less room, longer commute, neighborhood annoyances, etc.) to keep total spending relatively stable.

In the late 20th century, several of the classic cities with dense urban cores became very expensive. Agglomeration had been the traditional explanation for that. So, it seemed that they had suddenly tapped a deep vein of agglomeration value in the post-industrial economy. I used to believe that. I still do, but I think the scale of that value is relatively small compared to our current scarcity challenges.

More importantly, what happened was that every city created veto points for existing residents to block city-building. And, those veto points are especially powerful where there are a lot of people.

As I wrote the other day, “That’s why I don’t think it’s an accident, or a coincidence, that ‘we particularly regulate those communities that are really good at turning kids of poor parents into middle income adults.’ Cities have lots of economic potential and services for poor families because there are a lot of people there to be of service. They stopped approving housing when we gave locals too much power for the same reason - there are a lot of people there to object.”

The cities with the largest scarcity problem are the cities with the most agglomeration value - for the same reason. But, by the 1990s, the scarcity problem was the most important issue. And, you can tell by the shape of the price trends - the distributional consequences. The costs are much more elevated for the poor than for the rich. And costs rise much more than incomes do.

Families don’t tend to spend 60% of their incomes to move toward opportunity. They do tend to spend that much to avoid displacement - or at least some portion of them will - so that the families that choose to remain are self-selected as families willing to accept exceptionally high housing costs to avoid displacement.

The price of housing in the expensive cities isn’t determined by the aspirations of the newcomers. It is determined, on the margin, by the reservation price of displacement-avoidance. It is the families moving away that determine the cost.

It is no accident that the cities with perennially the highest rates of net domestic outmigration are the most expensive cities. And, it really is a flashing red light about the relative importance of scarcity vs. agglomeration.

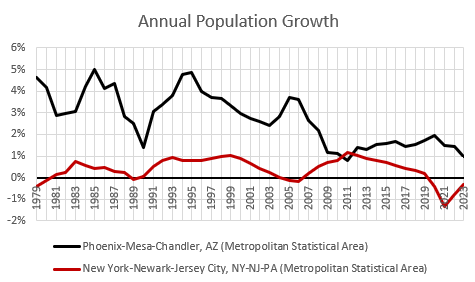

One question I would ask economists to grapple with is the cosmic coincidence that massive agglomeration value happened to appear only in cities that have effectively stopped growing (and, in fact, now have countercyclical population trends.)

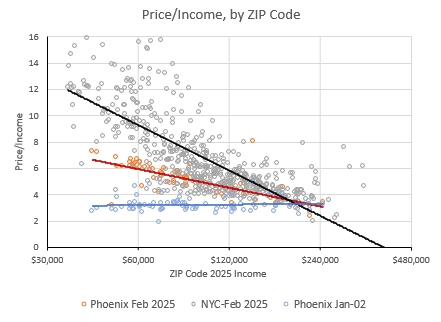

Then, after 2008, after housing production collapsed all across the country, every major metropolitan area also has gotten more expensive in the same regressive way. You can see this in Figure 1.

In New York City, the price/income ratio is 3x-4x in the richest neighborhoods and above 10x in the poorest.

In Phoenix, it was about 3x-4x in the entire metropolitan area in 2002. Today, in Phoenix, it is still 3x-4x in the richest neighborhoods and about 6x in the poorest neighborhoods. It’s halfway to New York City!

Did Phoenix suddenly tap into agglomeration? Is the cosmic coincidence doubling down? Every city that happens to create this magical infinite vein of agglomeration value also happens to stop growing? Weird! Did the economists who originally discovered agglomeration value think it would mainly show up in cities that aren’t growing?

Is agglomeration always and everywhere just unrelated to the size of the city? That seems to be the claim of this paper. Now Phoenix has agglomeration value of 6x incomes in the poorest neighborhoods and New York has 10x worth of agglomeration value. Does this mean that both of them could add 30% to their housing stock, and they’d still be at 6x and 10x, because agglomeration value matters but supply doesn’t matter? And somehow, agglomeration doesn’t scale with city size?

Or, what if agglomeration value does scale with city size. What if Phoenix had continued producing new housing at the same rate it had before 2008? That amounts to about 30% missing growth. What would Phoenix housing costs look like today? Would the low end now trade at 10x local incomes? Would it look more like New York City? And, if New York had built more, it would be up to 15x?

The cost of homes in New York City is determined by the migration outflow. At current flows, the marginal family at the bottom of the income distribution is willing to have housing costs associated with a 10x price/income ratio to remain in New York. If New York approves a bunch of new homes so that newcomers arrive and increase the agglomeration value, is that going to cause the marginal, formerly to-be-displaced family to consider New York worth 12x or 15x times their income, and they’ll stay and pay more?

Or maybe 30,000 of the families that moved to Florida last year when their price/income ratios hit 10x will see how much more agglomeration value there is with all the new housing, and they’ll be willing to pay 15x to move back.

Or will agglomeration increase prices more evenly across New York City? And if it does, then why isn’t that what it’s done up to now?

Or will agglomeration increase local incomes so much that home prices will skyrocket along with rising incomes. But, if that’s the case, why have home prices been previously rising even faster than incomes? Will incomes rise 30%, and that will entice families to bid housing costs up 50%, pushing price/income ratios at the low end up to 12x?

Or, maybe there is a bunch of pent up demand to live in New York City, so that if 3 million homes were built there, there are 3 million families just waiting to move into them if the rents decline by so much as a penny? I think it’s pretty hard to square that idea with the immense asymmetries in the cost of housing across New York’s neighborhoods. There are a lot of margins to compromise on. And the newcomers are making those compromises. The prices are high because the price setters are the soon-to-be-displaced families who have run out of compromises.

It is still true that added supply in New York City would, at first, not lead to declining costs. The displaced families have very inelastic demand until it hits the tipping point that they give up and leave. So, a few hundred thousand new units won’t lower costs much. First, they will just stop the outflows.

But, again, that’s about the leavers, not the arrivers. That is a claim that can be made “in sample”. We have years worth of data showing the behavior of leavers. Claims that housing costs will stay high or rise because agglomeration value outweighs scarcity value are way out of sample. And, frankly, I think if you really think about the practical math of it, implausible.

Phoenix

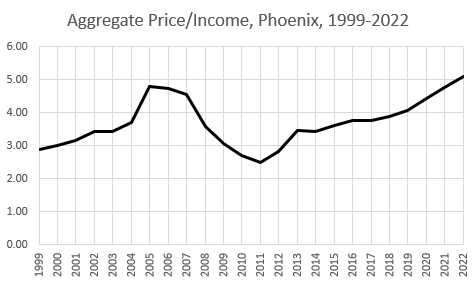

Figure 3 shows the aggregate value of Phoenix homes over time. It went from 3x aggregate incomes in 1999 to 5x in 2005, back down below 3x after 2008, and now back to 5x.

If Phoenix grows more, will it rise to 7x? Or does Phoenix have to stop growing in order to get that sweet New York-scale agglomeration value?

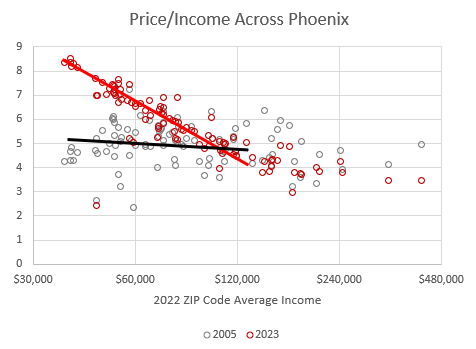

Oh, and by the way, what was going on in 2005? Figure 4 compares local price/income ratios in Phoenix in 2005 to the ratios in 2022.

In 2005, Phoenix didn’t look like New York City at all! Prices were high across Phoenix. Maybe that’s what agglomeration value looks like. After all, that makes more intuitive sense if agglomeration value comes from scale and is associated with aspirational newcomers.

Remember that time? Are there any papers in the journals about the amazing agglomeration value we were discovering out in the deserts? Surely there are!

Actually, 2005 was likely an unsustainable bubble from population inflows that would have eventually slowed down in any case.

Of course, most of the new population growth was from another big agglomeration city - Los Angeles. Tens of thousands of households were flowing into Phoenix in 2005. There are papers about agglomeration value in Los Angeles. And, remember, if economists are writing about your agglomeration value, that probably means that your poorest residents are flooding out into other cities by the thousands. So, I guess the temporary boost in Phoenix real estate in 2005 doesn’t have the same pattern as price/income trends in New York City or in 2023 Phoenix because the high prices in Phoenix were from Los Angeles’ agglomeration value, which led to massive outmigration from Los Angeles. That’s how it works, right? Help me understand!

Actually, by 2005, cities like Phoenix (which I call the Contagion cities) were taking in so much migration from cities like Los Angeles and New York City (which I call the Closed Access cities) that they actually had negative migration flows with the rest of the country. Maybe it was agglomeration value.

Is it easier to believe that its scarcity in such a gauche, uncool city as Phoenix? The idea that Phoenix, of all places, would have such expensive homes is so ridiculous that we made a suicide pact in 2008 to have a financial crisis until that madness stopped. Irrational exuberance, the economists called it.

Why didn’t anyone write articles in 2008 arguing that we should encourage more homebuilding in Phoenix because the agglomeration value would make it all worth it? Is there a study somewhere that can help me categorize rising housing costs as either agglomeration value or an irrational housing bubble, based on which cities are expensive?

I guess the agglomeration proponents would say you can tell if it’s an agglomeration city because the incomes are high. But, how can Phoenix ever get its incomes up, when all the poorest residents from the current agglomeration cities keep moving here? Will all the agglomeration value in Los Angeles that keeps U-Hauls streaming across the Colorado River forever prevent Phoenix from getting its own agglomeration value? Are we fated to just be a bubble city, and the whole country will commit itself to imposing recessions on itself whenever we pretend that Phoenix can attain agglomeration value too?

All snark aside, if Phoenix had continued building homes after 2008 at the rate they had been for decades before 2008, then, clearly, aggregate residential home values wouldn’t be 7x Phoenix incomes. They wouldn’t even be 5x. They would still be 3x-4x. And, there would probably be some extra agglomeration value from the growth. Maybe aggregate residential home values would be 3.45x instead of 3.4x Phoenix incomes.

And, maybe, more young professionals would be living in little apartments downtown next to a light rail stop rather than in big houses out in the exurbs. And, maybe their incomes would be a little bit higher. There would be agglomeration value, with all of its associated consequences. But, it’s a mole hill on the side of the scarcity mountain.

If New York City approved a bunch of homes - or frankly, just a normal amount, enough to even out domestic migration flows - its richest residents would still spend about 4x their incomes on housing, but its poorest residents might be able to spend 4x, too. And, maybe, on the trip from price/income ratios of 12x down to 4x, agglomeration value would land them, at the end of it all, at 4.05x instead of 4.0x.

Scarcity creates regressive housing costs. And since we imposed scarcity on the entire country after 2008, we now have cities like Phoenix who offer us several different scenarios of how housing costs throughout a city change based on both supply and demand shifts.

To me, the asymmetries in housing costs scream scarcity. But, if there is an alternative explanation that either denies scarcity or ascribes high prices to agglomeration, then the alternative needs to acknowledge this pattern and have a better explanation for it than scarcity.

Agglomeration value is real. We have a scarcity issue. No city, today, is going to increase its average home value today by increasing housing production. In fact, the total value of all real estate, even with all the extra homes, will be less than the total value of the homes we have now, if we increase housing production. I estimate that that will be the case for aggregate US real estate values for at least the next 10 to 15 million additional units. To think otherwise takes some pretty exaggerated mathematical assumptions, in my humble opinion. (I have a paper coming out on that topic soon.)

PS: Here’s a chart with Price/Income ratios across Phoenix in 1999, 2005, 2011, and 2022, in case this helps add context to the changes in Phoenix. The x-axis is 2022 ZIP code average income.

The question is, can supply lower prices in Phoenix in 2022? Is the difference between 1999 and 2022 agglomeration value?

Speaking of supply and demand https://sjcitizen.com/with-profits-dwindling-hundreds-of-st-augustine-airbnb-owners-are-looking-for-the-exits/

OT but I want to say it:

Some (mostly academics) have said the oversupply of finance led to the housing "bubble."

I lean to Kevin Erdmann's view on this, and the problem is housing scarcity, not finance.

But! An obvious, over-the-top red-flag example of financing leading to explosion in costs...is the college finance situation. The student loan programs.

Academics go mute on that.

Fat is everywhere on college campuses, where administrators now outnumber teachers. Where unionized workers (and I am very pro-worker) keep gardens and buildings clean, not students making some extra dough.

Could colleges have trades programs that teach plumbing, electricity, roofing and keep buildings operating?

Of course they could, and there are likely thousands of other ideas that could reduce the costs of education (including dumping offensive departments based on race or sex, that teach nothing. Or simply reducing the the number of students who go to a four-year college.

How BAs in business administration and law, and then pass the bar exams or equivalent and let it go at that? Why expansive grad school education?

OK, I said my piece.

Trump is cutting Ed Dept staff but not the huge student loan programs. Too bad