Supply has to be ridiculously low to create our peculiar affordability problem.

Maybe this is a repeat of some things I have written recently, but I think it can serve as a sort of summary statement of our problem.

Commonly, I see some combination of claims that builders purposefully limit construction to keep prices high, or housing can only be a good investment if prices are artificially propped up, or how this leads to an inevitably rising price floor that makes housing affordability a perpetually worsening problem.

It’s really frustrating how common these intuitions are. All of that is wrong. All of it is clearly refuted by even a cursory view of American housing markets throughout most of the 20th century - the Case-Shiller home price index that was famously flat as a pancake before a credit boom supposedly created a housing bubble in the 2000s. And now that home prices are elevated again after killing off the credit boom and then some, people just forget about the famously flat Case-Shiller index and come up with new theories about why the Case-Shiller index could never even, hypothetically, be flat.

In an essay I posted last year about filtering, I wrote.

Where homes are truly trickling down, they trickle down much faster than we would like them to. Updating and renovating them is work - it’s an important part of the residential investment and the expense of consuming shelter. Yet, the way that plays out for an individual new owner is that there is some house that needs them - that is just the right house for them, but it is less than they need. And, they build it up. They make it better - and more expensive - because it’s there, waiting for them to put their mark on its narrative as a source of shelter for generations.

Filtering - trickling down - where it actually happens is a narrative of rebirth, of regeneration, and of comfortable equilibrium. It is no coincidence that homes across Phoenix sold for 3x their tenants’ incomes in 2002. That coincidence would be impossible.

That is the comfortable equilibrium. That is because, where homes trickle down, families are in the favorable position of making the depreciated stock of homes more expensive to suit their preferences. That is naturally where an amply housed, comfortable city of people will end up. They will put their imprint on the depreciating housing stock. They will be a productive part of the narrative. And, plus or minus some variation that depends on property taxes, incomes, life spans, etc., they will comfortably maintain that stock of homes at an average price/income ratio of about 3.

And the important point I want to make for this post is that, in any given year, 99% of the housing stock is existing stock. In any given year, left to its own devices, the existing stock of homes will lose about 2% of its value in depreciation. If builders refuse to build a single new home because of “capital discipline” or whatever alternate theories you want to conjure up, the rest of the stock of housing will be worth 98% of what it had been the year before. As far as the structures go, they require continual reinvestment not to become less valuable than what we would want.

And, if builders don’t build new homes, it doesn’t make homes more valuable. Homes are worth as much as it costs to build new ones. It makes land inflated. It makes the land they have to buy to build more new homes inflated, and it also makes the land under all the old existing homes inflated. If real incomes, on average, increase by 2%, and Americans spend the same amount on housing the following year as they did before, then, the existing stock of homes will be 2% more expensive - a combination of a 2% loss on the structure and a 4% gain on the land.

I promise you that there isn’t a conspiracy among home builders to cut construction activity, which they consider to be their core competency and profit center, by half so that all of the existing homeowners can get a gain from their land, and land developers can get a gain on the new lots they will sell to those same homebuilders.

My more specific point here is that there is a ridiculous 7-sided debate going on with supply-siders (“Housing would be affordable if it was legal to build the homes people would choose to live in.”) on one side, and the other sides inhabited by (2) supply-side deniers (“We have more homes per capita than the our grandparents did.”), (3) anti-monopolists (“The builders won’t supply the market even if you let them.”), (4) libertarian excuse makers (“Everybody just loves to complain. The world has scarcity. Live with it.”), (5) debt mongers (“There are plenty of homes. It’s just low interest rates/debt/the Fed.”), (6) cost-based supply-siders (“We can’t build homes because high interest rates/costs/labor.”), and (7) egalitarians (“We don’t need luxury housing, we need affordable housing.”).

This isn’t a marginal debate any more. This is ridiculous. If there was a marginal shortage of homes that was anywhere close to debatable, then total residential real estate would still sell for a stable ratio to our incomes. Families that used to spend 30% of their incomes to rent 1,200 square foot units now spend 40% of their incomes for 800 square foot units. If we just had a large, but not ridiculous, shortage, they would be spending 30% of their incomes to live in 800 square foot units.

If there was no supply problem, when real household incomes increase by 2%, old homes would depreciate by 2%, then we would need to invest 4% of our incomes into existing and new housing just to keep total residential value, as a % of incomes, the same as before. In any world with supply conditions that are anywhere short of ridiculous, it takes a lot of work to keep homes from getting cheaper. Imagine how much work it would take to make homes unaffordable by investing more in them!? It’s a functional impossibility, if you think about it.

If there was a small, or even a relatively large, supply problem, the land under homes or the cost of building homes could inflate by 4% annually, and we could collectively spend the same percentage of our incomes on housing by reducing our investment in our depreciating structures. We would spend the same on housing, but we would live in worse homes as a result.

It doesn’t matter if new homes are built and they are all replicas of Versailles. The other 99% of the stock of housing is getting cheaper faster than we could possibly want it to. There is no way that the entire stock of housing could be unaffordable because of what builders are building. The only thing that can ever possibly become unaffordable is the land homes sit on. And they can only become unaffordable if builders are prevented from building more.

Our supply problem is so ridiculous that many households have 2% real income growth, their homes depreciate by 2%, the land under them appreciates by 5% or more, and their total housing expenditures are growing faster than their incomes.

That is really the only sustainable way to get expensive housing. Families have to be in such dire, undersupplied markets that they need to trade down faster than their home depreciates in order to keep housing expenditures stable. Once they are in that context, some families will pay ransom rents for the land under their homes in order to avoid displacement.

Now, don’t confuse the distribution of housing with its total value. In a city that obstructs new housing so fiercely that land values are outpacing the depreciation of homes plus the increase in incomes, every family will be spending more and more of their incomes on land rents. Families who can’t afford them any more have to move away and abandon both their depreciated homes and their inflated land. And other families who are trying to avoid moving away might trade down to a more depreciated home so that they can continue living in the city by paying the elevated land rents.

That’s inevitable. When housing is blocked, families must reduce their housing consumption at a rate faster than the natural depreciation rate of homes in order to stay ahead of rising land rents. When that happens, of course families with more wealth and income will move into the less depreciated homes that the poorer families left behind. And, some might even invest improvements in those homes in the process of all of that sorting into and out of the homes.

Those investments aren’t the reason the land is so inflated. To conclude that is to miss the forest for the trees. The suburbs of San Francisco are the most clear examples of this. In Laurel, Mississippi, a new family might buy a fixer-upper for $50,000 and put $150,000 of renovations into it. In Palo Alto, that same fixer-upper would cost $1 million. Maybe the new owners will put $400,000 of housing on the $1 million lot in Palo Alto. But, clearly, the San Francisco area isn’t unaffordable because too much upkeep is being invested in million dollar lots.

Before 2008, families with below-median incomes in cities that blocked housing so thoroughly that population growth was stamped out were in the position of having to downsize faster than their homes could depreciate. Housing expenditures had to rise higher than household incomes because somebody was going to have to move away. It’s simple math, and the math works through land inflation. If you block new housing and a stagnant population wants to keep spending a stable amount of their incomes on a depreciating housing stock, the land under existing homes has to rise high enough to make someone feel poor enough to move away. That’s why Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York City are still expensive even as their populations decline. Once you’re in that ridiculous situation, the land has to accumulate inflation at a faster pace than homes depreciate, because families start paying simply for the right to stay put.

That’s America in the 21st century. Now, families with below-median incomes are in that position in cities across the country.

We don’t have a marginal or arguable housing shortage. We have a ridiculous housing shortage, and the patterns in rent and price inflation that it creates could only appear under ridiculous conditions.

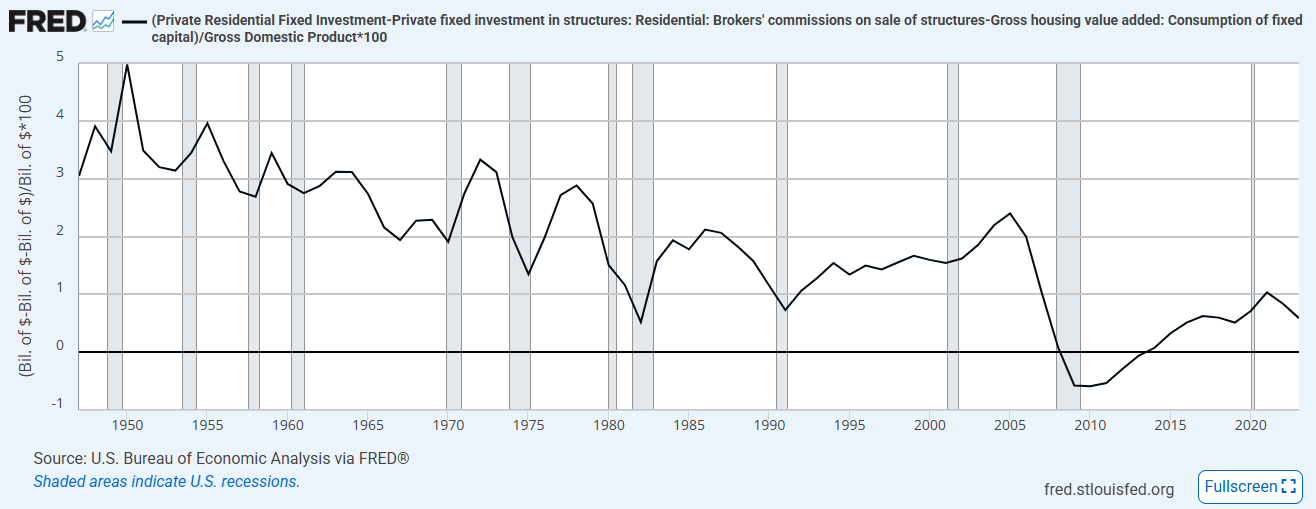

Net residential investment as a percentage of GDP has been lower than the lowest points of the deepest post-WWII recessions for 18 years straight and rents are taking up more of household incomes than ever before. We’ve put families with below-median incomes through an 18 year depression. It is the only possible outcome from our ridiculous housing shortage. It’s math. Everyone pays more for the land under their homes until somebody chooses to downgrade their living conditions faster than the homes could depreciate.

We aren’t going to solve that problem by pushing residential real estate lower. When you’re in a deep hole, the first thing to do is to stop digging.

This isn’t a debate. This is ridiculous.

You can view the “We don’t need luxury housing, we need affordable housing.” obstructions through this lens.

Luxury housing moves that black line in Figure 1 back up out of depression level lows. That’s what we need. In that case, families will sort themselves out throughout the stock of homes like they did for a century when the Case-Shiller index was flat.

The “affordable” housing supporters, instead want to create new housing that accelerates the process of depreciation. Instead of creating new options to move up into, they only want options to be displaced down into.

“If we only build homes for the rich, then only rich people will be able to live in the new homes.”

Yes. Everyone else is just hoping their depreciated housing this year will be enough to keep ahead of their rising land rents. If they could stay in their depreciating homes without spending more, that would be an improvement, and it would be better than moving into new cheaper homes to accelerate the depreciation. And, if we build enough homes, the land will decline in value.

Currently, so many households are in housing poverty that they will be happy to let their homes depreciate so that rent next year takes 48% of their incomes instead of 50%. That is the choice they will make. Eventually, maybe their rent will take 30% of their incomes, and they will choose to upgrade or improve their homes. That would be the solution.

The solution will start to improve their lives immediately, but it might take years to improve it so much that they can actually return to the regenerative process that the residents of Laurel enjoy. You may imagine that increasing the number of compromises they can make under today’s broken system will lower their expenses immediately. That doesn’t make it a solution. And throwing money at specific families while enforcing the broken system isn’t a solution either. It’s just a self-congratulatory part of the problem.

As for denier groups 2 through 6, I suppose you could categorize them according to which decades in Figure 1 they seem to think didn’t happen.

I miss working in housing policy but I do not miss the endless debates with supply-side deniers. I am on my hands and knees BEGGING them to look up the Census Department definition of vacancy before telling me that vacancies went down because of Airbnb.

Great piece. Two questions

Everyone in NYC says they want affordable housing. But, as you point out, and as most people do not seem to understand, land costs make it impossible to build NEW affordable housing. A half acre lot in Brooklyn now costs between $5 and $20 million dollars. I'm sure that zoning etc has something to do with that but it isn't everything. Are there any credible estimates of how much regulation adds to cost in NYC, LA, or SF? Or, for that matter in the NYC suburbs.

Do you understand what is going on in Florida? I've heard prices are collapsing, but I assume that's an exaggeration . I assume insurance is the big problem.