Though it is counterintuitive, renters rank high among the victims of the 2008 mortgage crackdown.

In the analysis below I use the estimates of households by tenure from the Census HVS survey, historical table 8. And, I use data from Tables 2.4.4 and 2.4.5 from the BEA, estimating real expenditures and price indexes for rental values on both rented and owned units. From this, I can estimate consumption of housing for renters and owners per household.

First, a brief review of what has happened and how rented vs owned and new vs existing fit in the process.

Supply at the High End Drives Costs at the Low End

Figure 1 is the prices of homes throughout Atlanta, arranged by ZIP code income. (Zillow rent data only goes back to 2015 and isn’t as comprehensive, so we have to use prices as a proxy.) These are ZIP codes, but I think it will be easiest to think of this conceptually as individual homes and households.

The Atlanta market was pretty normal in 2002 and 2006. The left end of the scatterplot is mostly rentals. Most of the homes in ZIP codes with above-average incomes - to the right - are owned.

The way functional housing markets work, and the way Atlanta’s worked before 2008, is that new homes are mostly added in the upper half of the market. Think of these dots slowly moving up and to the right over time as the composition of the city changes with new homes.

This is the filtering process. Those new homes are claimed by families who tend to have higher incomes, and the existing stock of homes becomes available for the entire range of residents to move into. Like the orange (2002) and green (2006) lines, the Atlanta market should have just kept marching upward and rightward. New homes would push the front edge of the housing stock up, and older homes would become the left end of the housing stock as incomes in the city rise over time.

This has a few ramifications:

In order to provide homes for the poorest residents, you don’t have to fund a lot of new building aimed at the left end of the distribution of households. Most of the housing that will be available at the left end of the plot in 50 years is already there now. Mostly, they will stay in place while the city moves slowly to the right.

Not every dot will stay in place. Both houses and the people living in them change. Some neighborhoods might gentrify, and move up and to the right. Others might move down and to the left. In general, houses naturally depreciate and move down, and in any city - even ones where housing is filtering down nicely, homes that are transitioning into older, more affordable neighborhoods, are occasionally upgraded and updated to meet their current residents’ preferences.In other words, even in a functional market with downward filtering, homes depreciate (move down) faster than they filter (move left relative to rising incomes in the city). (If you have the time, I suggest this essay -“Filtering on HGTV”- on the process of filtering. I think it’s one of my best pieces of writing. It offers an uplifting, yet realistic, way to think about the filtering process, and might help visualize how those dots are moving around on that chart over time.)

New homes don’t have to be affordable for the typical family. The median family in a typical city lives in a home that is 50 years old. In a typical year, only about 1% or 2% of homes are new homes. For every new home that “pencils” - that meets the idiosyncratic preferences of a given set of families within the metro area - there can be countless units that don’t “pencil”. In a city with a functional market, there should be many aging neighborhoods that are selling at discounted prices, so that a new home in those neighborhoods wouldn’t be justified by relative cost.

This year, the typical new home in Atlanta will probably sell for well over $500,000. New apartments also tend to be more expensive than existing apartments. The new units are slowly moving Atlanta up and to the right. The new dots keep slowly populating the leading edge and generally the right hand side of the scatterplot. When they don’t, then the existing dots have to move to the right (new residents with high incomes buy existing homes) and, more so, move up (existing residents with lower incomes pay higher rents and prices to avoid displacement).

In a functional market, every regression line would line up on the same diagonal path that the 2002 and 2006 lines are. They would just be moving up along that path. In 2050, incomes in the richest ZIP codes in Atlanta will be around $400,000 and home prices in those ZIP codes will be $1.2 million. If its housing market returns to a functionally supplied market, incomes in its poorest ZIP codes will be $60,000 and homes there will sell for $240,000. Everyone would be moving up and to the right.

In 2011, high end Atlanta was on that path, but low-end Atlanta was too low. Today, high end Atlanta is on that path, but low-end Atlanta is too high.

Things like construction costs mostly affect the size and quality of the new units. (And the extent of upgrades and renovations that are applied to depreciated units to keep pushing up the low-end of the distribution up to that common diagonal path.)

Different costs and construction productivity affect the details of each of those dots (size, quality of upgrades and fixtures, etc.), but not the trendlines in Figure 1.

Consider the real home price that Case-Shiller says was level, plus or minus 20% for more than a century, or the Fed estimates of real estate values as a percentage of GDP that were flat from WW II to the 1990s. The size and quality of homes changed drastically over that time. In a functional housing market, spending on housing is very sensitive to income. The quality of the homes changed to keep housing costs anchored to those very stable long term spending norms.

When the state of the housing stock is determined by the cost of construction, then rents, prices, and spending stay at stable portions of incomes, and the quality and size of the houses change. When the state of the housing stock is determined by legal opposition to funding and building houses, then rents, prices, and spending rise as a portion of incomes.

In other words, if the Atlanta housing market was still functional, then today we would expect a family making $80,000 to live in a house worth $240,000, just like in 2006. If construction costs had been low since 2006, it might be a 2,000 square foot house with an upgraded kitchen. If costs had been climbing, it might be a 1,600 square foot house with an old kitchen. But the dots would be in the same place.

The condition we have been in, where housing costs swing wildly at the low end while tethered at the high-end, is really, really weird. It is really hard, actually, to deviate much from that linear diagonal path that Atlanta was on in 2002 and 2006.

The weirdest swing was the swing to 2011. That could only happen with deep, sadistic tightening of mortgage standards. That was not a sustainable pattern. You could not get that pattern with oversupply. Builders couldn’t build into that condition. And builders will not build while in that condition, so that rents inevitably rose until the price pattern moved back up to the natural equilibrium (and now has even raced past it).

(I suppose you could say that before 2008 some cities, like Detroit, sort of created a pattern similar to Atlanta in 2011 with a combination of depopulation, regressive property taxes, and highly negative neighborhood amenities at the low-end.)

The upswing to 2024 is also pretty hard to do. The only way to get that pattern is to obstruct new homes so harshly that the land under existing homes appreciates in value faster than the home itself can depreciate. So, homes filter up. It takes a lot of work and a lot of local state capacity to keep making that happen.

Cities like LA, New York, and San Francisco have done that hard work, so they are permanently in the condition that Atlanta is in in 2024, only worse. In those cities, the equilibrium home price is determined by the balance between rising excess land value and the rate at which families with lower incomes move away to escape it. If the economy is good, rising land value pushes rents up enough to increase domestic outmigration.

So, there are 2 different things going on in 2011 versus 2024. It isn’t possible to create the 2011 trends in Atlanta housing prices through supply. In 2011, the mortgage crackdown pushed low-end prices lower, but rents remained stable. That was an unsustainable condition. The way Atlanta evolved from that condition back to the normal pattern of home prices was rising rents.

(It’s a complicated story how the line remains above the 2002-2006 level, having to do with rising land values. I am not entirely sure how this will proceed. Maybe in a city like Atlanta, the rise of single-family build-to-rent will pull it back down to that natural path. That’s a discussion for another post.)

The main point I want to make here is that the supply crunch after 2006 creates uneven rent inflation. Rents go up much more at the low end than at the high end. And, the low end is where most of the housing is rentals. So, the effect of inadequate building (which happens mostly at the top end) is to raise rental values more in low-end neighborhoods, which contain more rental units.

When there aren’t enough new dots populating the right end of the plot, the dots on the left end move higher.

On to the national numbers.

In 2008, the mortgage crackdown locked millions of families out of financing, existing owners lost homes in foreclosures, and homebuilding collapsed. Growth of total expenditures in housing declined sharply and some of those expenditures moved from owner occupied to rental housing.

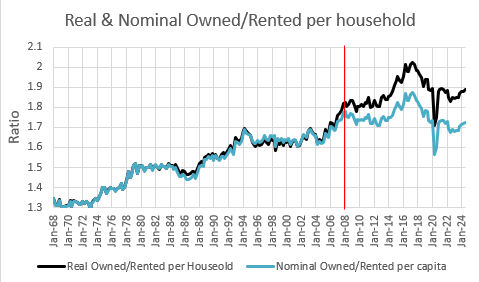

Figure 2 shows the ratio of owned units to rented units (red) and the total rental value of all owned units to all rented units (black). Homeownership rates started to decline well before 2008, as you can see here, and then continued to. Homeownership rates had been rising since the mid-1990s. Additionally, from the mid-1980s to the Great Recession, owned homes were increasing in value more than rented units. (It seems plausible that tax changes in the 1980s which favored mortgage debt were responsible for at least part of that.)

From 2007 to 2012, the proportion of owned units declined (lowering the red line), and the mortgage crackdown also caused the values of owned units to decline (lowering the black line even more sharply).

(The BEA estimates the rental value of owned homes, and that is what is reported as expenditures on housing in the estimate of GDP, personal consumption expenditures, etc. That is the concept I am using here. Even owned homes have a rental value. And it changes over time because of both real investments and price level changes. The fact that owners also act as providers doesn’t change that, and in the end, the economics of the rental consumption of the home determine the long term economics of its ownership.)

Figure 3 shows total real expenditures on owned and rented housing. You can see the shift from owned to rented here.

Figure 4 shows real expenditures per household for owned and rented homes. A significant portion of the housing stock switched from owned to rented from 2008 to 2015. So, on a per-household basis, real rental expenditures after 2008 are a bit higher for owners and a bit flatter for renters than the total expenditures were.

There are a couple of other things to note here. You might generally see the claim that there is not a housing shortage because homes are larger and nicer than they used to be. They are just more expensive because they are better.

That talking point is outdated. Real housing expenditures per household have been flat for nearly 20 years for homeowners. Longer for renters. It’s been a generation since homes were getting better on average.

The average real rental value of both owned and rented homes has been flat since 2008. Actually, from its peak in 2010, real expenditures per rental household have declined by about 5%.

But, costs have not declined. Excess rent inflation has been unprecedented. And, as I outlined above, rent inflation has been higher in low-tier housing, and thus, higher in rental units. Figure 5 shows the difference between rent inflation on rental units and the BEA’s estimate of rent inflation on owned units since 1980. Rent inflation, in general, has been elevated since 2000. But, digging deeper, rent inflation has been much higher in rental units than in owned-homes. It has accumulated to more than 9% additional rental expenditures on the average rental unit compared to the average owned home.

Figure 6 is another ratio - the ratio of expenditures of owners per household to expenditures per household of renters. The blue line is the nominal expenditures. The black line is real expenditures. In other words, the black line is what owners get compared to renters. The blue line is what owners have to pay for it compared to renters.*

Relative total expenditures on housing between renters and owners have not changed since the Great Recession. In 2006, the average owned home had a cash rental value about 70% higher than the average rental. In 2024 it is still about 70% higher. But, the average owned home is now about 90% better than the average rented home (nicer, larger, etc.).

Figure 7 compares excess rent inflation on rented homes and excess rent inflation on owned homes since 1995.

Basically, the simple story of what’s going on in Figure 7 is that the rental units tend to be on the left end of Figure 1 and owned units tend to be on the right end.

What it all adds up to is that renters are spending more to get less. Owners are spending more to get the same. But, mostly that’s just downstream of the broader issue, which is that when new housing is unsustainably low, families with low incomes have to spend more to get less. Those families tend to live in neighborhoods with more rentals.

The only ways to reverse the regressive rent inflation are either a massive expansion of multi-family construction or the return of more accessible mortgage lending. In the meantime, the emergence of a single-family build-to-rent sector might stop the bleeding as long as it remains legal.

* This might seem confusing or too abstract for some readers. I know that the owners don’t actually *pay* rent for their homes. But, just because they don’t write a check to themselves each month doesn’t mean it isn’t a real form of consumption. This analysis is about the condition and rental value of the housing stock, so these are the relevant measures.

Maybe just pretend that every homeowner pairs up with a neighbor with an identical house and they agree to rent from each other, if that helps you think of the homes’ rental value in concrete terms.

Yup, yup, yup.....and to give an indication of how much of an uphill battle we have here in the Boston metro region I can point to recent pushback against efforts in Cambridge to eliminate single family zoning. Homeowners have raised the battle flag of Property Values in their struggle against housing production. For those of you who don't know, Cambridge is the Loth Lorien of self-righteous liberalism on the East Coast. This means that neighborhood character--which mostly consists of high density housing stock built on swampland--is a sacred trust that must endure for eternity. Property costs have been so high for so long that one institutional landowner made the wise decision of buying huge swathes of land on the other side of the river in Alston to have a blank slate for expansion. But that's a side note compared to the general torpor in Cambridge that shows no sign of abating. The preferred solution for "affordable" housing in all left-wing kingdoms is public housing AND inclusionary zoning mandates for any large scale private developers. The public housing stock is of course in bad shape and large scale development generally has a 20 year planning period.

This is the agony of being a Kevin Erdmann fan.

You know some truths about the US housing market, a market central to US prosperity and real living standards and much else.

But these truths are never discussed anywhere else, or if so, fleetingly.

Do we want most people to buy into a mostly free-market system? I do.

Can we convince people to buy into a system that delivers lower living standards (after rents, taxes) generation after generation?

Real wages for young men (even before residential rents) are lower now than in the late 1960s.

Why are so many angry, and voting for fringes, or joining incoherent anti-US movements?

Well, a lot of reasons, I know. But housing is in the middle of the mix.