Rent Inflation and Housing Supply & Demand

The BLS has been working on alternative rent inflation measures. They now publish quarterly estimates of rents on all tenants and rents on new tenants. The all-tenant measure is not too much different than the published CPI rent measure. The new-tenant measure is more sensitive to current market conditions.

Basically, the CPI rent measure lags true inflation, but it is mostly because actual rents lag. Rents on existing tenants are sticky for a number of reasons, including that landlords sometimes voluntarily keep rent increases moderate for existing tenants and that leases are only renegotiated on a schedule.

So the all-tenant estimate and the CPI rent estimate are reasonable estimates of actual rental expenditures. The new-tenant estimate is a better estimate of current, real-time market conditions.

And, since most rent in the CPI and GDP numbers is the rental value of owned homes, none of this matters much to aggregate domestic income and inflation estimates. For homeowners, this is irrelevant to actual cash expenditures, but it is relevant to home values and to an abstract estimate of consumption.

For these reasons, I prefer to simply remove the shelter component from inflation estimates. But, if shelter (and rent) are relevant to inflation estimate, then the owner-equivalent rent that composes the majority of it should reflect current market conditions. The new-tenant measure is the more accurate measure for that. There is no reason to muddy the estimate of imputed homeowner rental expenditures with a bunch of lags in rental contracts.

Figure 1 shows quarterly trailing annual percentage changes for the All Tenant Rent Index (yellow), the New Tenant Rent Index (black), 95% confidence bands for the New Tenant Rent Index, the Zillow US median rent estimate minus a 0.8% adjustment for compositional changes (blue), and core CPI inflation for all the other categories except for Shelter (green).

The first thing that jumps out here (slightly off topic) is how completely useless core non-shelter CPI is as a recession indicator. 2008-2010 was a once-in-decades shock, and core CPI inflation didn’t even budge.

The decline in New Tenant rents after 2008 is an indication of how much a once-a-generation demand shock, largely focused on housing, can affect rent trends. The answer is, “Not much.” Increases in supply are much more slow moving than changes in demand - especially the changes that happened from 2008 to 2010. And even that massive change in demand didn’t create much rent deflation.

It is possible that an amply supplied market would be more sensitive to a negative demand shock. But, we are so low on supply - and we were even so low on supply in 2008 - that there is plenty of pent up demand for utilization of the existing housing stock if rents even hint at stabilizing.

If you think of demand shocks as changes in housing per capita, then what happened in 2008 was that suddenly the “Closed Access” expensive cities (NYC, LA, San Francisco, Boston) had room for more people. All those cities saw a brief rise in population growth during the recession. And rental vacancy rates in those cities topped out a bit over 6%, which is lower than the national rental vacancy rate ever gets.

Figure 2 and 3 can help us think through the scale of these changes. Figure 2, from left to right, shows the change in per-capita housing demand, the change in population, and the change in the housing stock - all estimated as a percentage growth of housing.

The Contagion cities are Florida, Arizona, and inland California. The Closed Access cities are NYC, LA, San Francisco, Boston, and San Diego.

In the Contagion cities, housing production is the dependent variable. It reacts to changes in housing demand and population:

Housing production = Population growth + per-capita housing demand.

Since housing production in the Closed Access cities is low and relatively fixed, population growth has to be the dependent variable. When housing demand rises, population has to decline:

Population growth = Housing production - per-capita housing demand

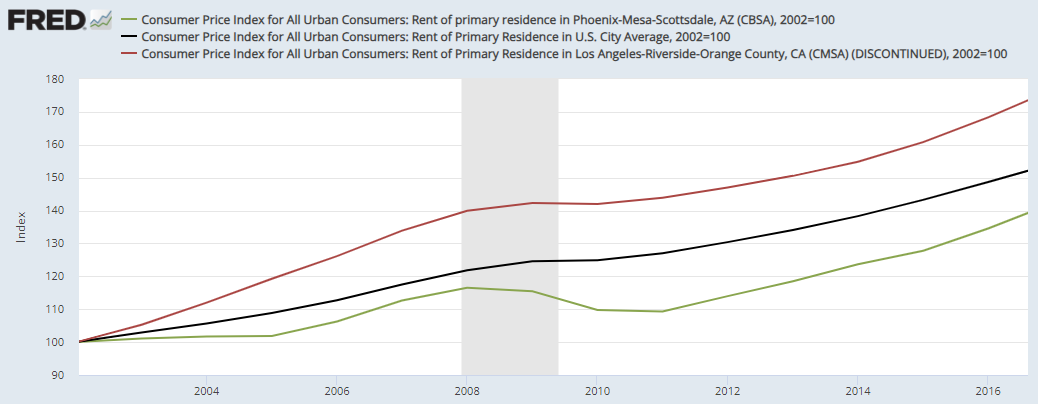

Figure 3 compares rent inflation in the US, LA, and Phoenix.

When housing demand was high, population had to decline in LA. Rents had to rise in LA to drive families out. Since supply was elastic in Phoenix, Phoenix simply built more homes and rents remained low during the boom.

The first thing that happened, from 2005 to 2008, was that federal policymakers engineered a slowdown in housing supply. This caused rent inflation to rise in cities like Phoenix. The New Tenant rent index only goes back to 2005, but that is far enough that in Figure 1, you can see that rents increased in the years before the Great Recession when housing starts declined sharply.

Then, federal policymakers engineered the widely popular financial crisis in 2008. The subsequent foreclosure crisis largely happened from 2008 to 2012, well after home sales and housing starts had bottomed and prices had started to collapse. Per-capita housing demand went negative. It had been nearly 1% annually in 2004 and 2005. By 2009 to 2011, per-capita housing consumption declined by about 0.5% annually.

Between declining regional population growth trends and declining per-capita consumption of housing, the growth of housing in the contagion cities went from 3.5% to 0.5% in just a few years. Nationally, it went from 2% to 0.5%. The contagion cities had a demand shock about twice as large as the national demand shock.

National CPI rent inflation went from about 4% to 0% and in Phoenix, it went from about 4% to -4%. This suggests, very broadly, that a 1.5% difference in the supply/demand balance is associated with a 4% difference in rent inflation.

In the years leading up to Covid, occupied housing was increasing by about 1% annually and rent inflation was running at about 3%. Population growth has declined, but per-capita demand is positive again. All else equal, doubling production today should be associated with zero rent inflation.

Looking back at Figure 1, the recent decline in New Tenant rents isn’t plausibly from a change in supply. There has been no significant increase in supply. It could be from some decline in per-capita housing. If that is the case, it is either a temporary snap-back from the Covid era demand spike. That could be associated with a temporary drop in rents, but it would be unlikely to be permanent. A permanent decline in per-capita housing consumption would probably be associated with declining supply, as in 2006 and 2007, and rents would increase in that scenario.

It seems likely that the recent number will be revised upward, especially since it hasn’t been matched by Zillow rent estimates, which tend to follow a similar path.

Roughly speaking, it will probably take production levels closer to 2% of annual housing growth to get rent inflation to zero. In 2005, when housing was increasing by almost 2%, supply-related rent disinflation briefly brought it down to about 2%. Population growth is lower today.

We just aren’t anywhere close to a production level that would create negative nominal national rent trends. Negative demand shocks are unlikely to persist on their own, and I think we have moved past the point where policymakers will try to create one like they did in 2008, though the idea is still popular among a large number of numbskulls.

Broadly speaking, we should expect, or at least hope for, housing production numbers a bit higher than they are today, rent inflation between zero and 2%, and a long, boring ride back toward reasonable costs.

There is little reason to expect supply-motivated trends on that path that are strong enough to be disruptive. Maybe there are some multi-family investors who were penciling in 6% rent growth out to the horizon in 2021, and the bondholders will end up with their properties. But, beyond those transitional changes, there is no reason to think that a positive supply trend from here will be so deflationary that real estate values become nominally disruptive or incapable of producing profitable new projects.

It may seem like they couldn’t be profitable, but eventually, land prices and other costs will moderate.

The usual suspects will probably be calling for or predicting 5% rent deflation and recession for a while. There will be cherries to pick to scare monger about it. It’s not going to happen, except for maybe a blip and a bloop or a very localized situation here and there.