Thought I’d post some quick follow-up points to the earlier post.

The problem starts with the fact that an interest rate target is a terrible way to communicate monetary policy. But, given that we do, it is hard not to describe it in those terms.

There are 2 points within the discussion of the earlier post. (1) The Fed Funds Rate target is not a reliable indicator of monetary policy. And (2) even so, it fails on its own terms.

In the original post, I used the Cleveland Fed estimate of expected inflation. My point was that when the Fed first started raising the target rate and inflation dropped sharply and permanently, the rate wasn’t remotely high enough to have caused that drop. And, since expected inflation actually peaked in June 2022 - the last month with high inflation - and was still at that peak in September, it would be hard to argue that Fed policy was working through expectations.

The market was still becoming less confident in the Fed’s ability to maintain control of the trend inflation even as transitory inflation dissipated. As it should have been! The Fed was loose! As they should have been!

The shortest market inflation spread that the Treasury reports from TIPS bonds is 5 year expected inflation. It is included in Figure 1. That did peak in March of 2022, when the Fed implemented its first small hike. So, there is some indication in that measure of a market reaction to the initial rate hike. Though, even here, (1) inflation expectations were well below actual inflation at all times, because the market understood the inflation to be transitory and (2) the contraction in 5-year expected inflation was pretty mild. Expected 5-year inflation today with a 5.25% target rate and inflation at about 2% is only about 10 or 20 basis points lower than it had been before March 2022 when monthly inflation trends were hitting double digits.

The market always expected inflation to subside soon, and the run-rate expected inflation level has changed little through all phases.

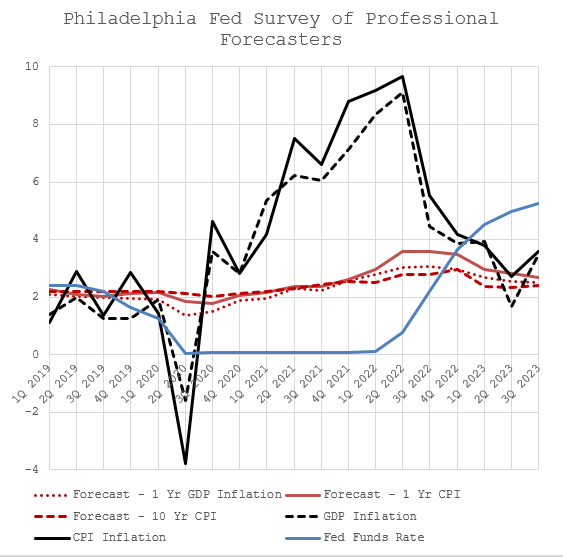

Figure 1 had 5-year market data and a 1-year quantitative estimate. Figure 2 has survey data from the Philadelphia Fed. The survey data also does not support the expectations channel story.

If the Fed brought down inflation through expectations of future rate hikes, nobody told the professional “expectors”. Professional forecasters’ expectations of 1-year inflation had been slowly rising through 2021 and early 2022, and then accelerated in the 2nd quarter of 2022. Even in the 4th quarter of 2022, 1-year inflation expectations were near their highest levels - a full percentage point higher than inflation expectations had been in the 1st quarter of 2022 - the last quarter with a zero Fed Funds rate.

Again, this makes sense if inflation was transitory. Forecasters always expected current inflation to recede on its own. As transitory inflation became extended with a negative real Fed Funds target rate, forecasters started to view the run-rate inflation trend as higher. And, they should have! The Fed was moderately loose. Target rates are a terrible indicator, but it shouldn’t be controversial to expect deeply negative real rates to be at least a little dovish. It makes eons more sense than claiming that a couple meager rate hikes can cut inflation by 4-5% in a couple of months.

One problem is that there aren’t perfect alternative measures of monetary policy stance.

Currency in circulation and other monetary indicators, like M2, are more directly related to actual money supply than the Rube Goldberg process that conceptually connects interest rate targets to inflation. And, they have long-term parallels with inflation. But, their short-term parallels are a bit hit and miss.

I agree with Scott Sumner that nominal GDP growth is probably a better indicator of monetary policy, and a coherent approach would be to manage cash injections through some type of forward NGDP futures market.

If nominal GDP growth is the best indicator of monetary policy, then there really isn’t any indication of a sharp tightening in 2022 in Figure 3. There had been some catch-up growth in 2020. Probably some fiscal stimulus growth in 2021. And then nominal GDP growth started a glide path toward the 4% to 5% normal trend. In the first half of 2022, this was associated with high inflation because extended Covid-related supply shocks were continuing to hurt real economic activity. Those were temporary (which is why the inflation was temporary).

Looking at GDP growth, it’s really less of a picture of dove or hawk. It’s more just, negative shock, then recovery, then a slow glide back down to regular growth levels. In 2022, when inflation was declining sharply and the Fed was raising rates, nominal GDP growth was above a neutral trend associated with Fed mandates, but it was persistently declining toward that trend. To the extent that the Fed has some control over these trends, I can’t imagine a path that could have been much better.

Nominal GDP growth declined from 8.1% in the 2nd quarter of 2022 to 7.0% in the 3rd quarter. GDP inflation went from 8.7% to 4.4%. Most of the change in price trends came from the change in real economic activity. GDP was high, but slowly gliding down to normal paths. In other words, there had been transitory inflation from a supply shock, which clearly hit in the first half of 2022 and then receded. There was no reason for the Fed to counter that. Would anyone have benefited if the first half of 2022 had the NGDP growth necessary to push inflation down to 2%? No. Obviously.

The inflation was obviously transitory.

The transitory inflation obviously should not have been countered with more monetary tightening - certainly not enough to hit a 2% inflation target.

But, back to the main point of these posts, I am flummoxed that the popular reaction to all of this is to put interest rates front and center and to give them a causal role.

It seems to me like there are parallels here to the way mortgage rates are approached in housing. There are things that rates affect. But, there are things they don’t systematically affect. It seems as though they are so conceptually favored that they can be treated as if they are causally central, even when there is no compelling evidence at all. The evidence is created from the presumptions themselves.

The communal confirmation bias creates its own evidence. Once the transitory inflation was extended by the 2022 supply shocks, it was inevitable that the false narratives of centrally important Fed target rates would get constructed. Eventually, with such negative real rates, a marketplace slowly losing faith that inflation would remain anchored, pundits and critics demanding action, and quantitative models saying to hike, eventually, the Fed would have to dip a toe in the hiking waters. And once they did, rate hikes became the presumptive cause of all things monetary. Since the inflation was transitory, it was bound to dissipate, and now the Fed hikes were there to take credit.

We are so fortunate that we have managed our way through this so well when Fed communications after all of this frequently are along the lines of “We have brought inflation down a lot, but there is more work to do.” No. and No. And yet JPow! continues to find the right path.

Well, like I always say, if you are not confused, then maybe you really don't understand monetary policy.

I agree with this post, and that the Inflation Bogeyman was again over-rated.

Not sure about the connection between monetary policy and inflation.

The way M2 grows is circumstantial; that is (primarily) people who sell real estate get huge gobs of money. (Buyers borrow money from commercial banks, who print the money, give it property buyers, then the buyers hand the loot over to sellers).

Would anyone design this property-goosing to be the mechanism to effect macroeconomic policy? But as fractional-reserve banking preceded central banking, that is what we have.

There is the additional question about QE. I think this is also an expansion of the money supply and a better one---essentially money-financed fiscal programs.

Money-financed fiscal programs could replace all this jiggering of rates and reserves, the clunky Federal Reserve and commercial banks, and recurrent starving or force-feeding of the property sector to obtain macroeconomic results.

Plus, taxpayers would not face ever-mounting bills for having borrowed money.

Japan is interesting.