GDP Update 1st Quarter 2024

JPow! continues to roll us right along the 5% nominal GDP trend. Just an amazing bit of leadership. This quarter, real annualized growth was 1.6% and inflation was measured at 3.1%. Obviously we want more real growth and less inflation, but these measures have a lot of noise, quarter to quarter, so I really don’t think much attention needs to be paid to it.

The market monetarist approach says just focus on nominal GDP growth, and JPow! quickly reversed the sharp contraction, overshot by just a smidge, and now has us moving just above the trend level but at slightly below 5% growth in the current quarter.

Perfect landing. No notes. We are now 18 months into a soft landing. The only question that remains is how long everyone will continue to pretend it hasn’t happened yet.

Of course, real GDP growth is below the trend that would normally be associated with 5% nominal GDP growth and 2% inflation.

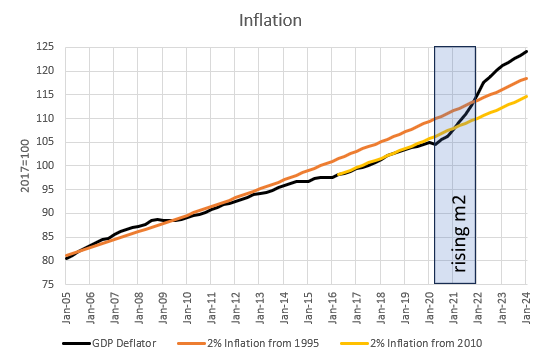

And, of course, the temporary bout of transitory inflation put us above the trend of 2% inflation. But, Covid did that to us. I suspect we might still have a period of catch-up real growth and below average inflation, to move those measures back toward their long-term trendlines. And, obviously more real growth and less inflation is better. But, if that doesn’t happen, it would be defeatist and self-abusive to use monetary policy to try to make it happen.

The mismeasurement of rent inflation still has everyone overly worried about inflation, so the bit of a bump GDP prices took this quarter seems concerning to them.

Much of that extra inflation is also still from problematic housing measures. “Personal consumption expenditures: Services: Housing and utilities” annualized inflation came in at 6.3% for the quarter. As I have discussed here, most of that inflation is still just the lagged effect of the methodology from an increase in market rents that ended along with the rest of transitory inflation nearly 2 years ago.

If we must use an interest rate targeting framework to discuss monetary policy, then, I may eventually have to fully capitulate to any concerns I have expressed about JPow’s leadership. I have routinely been more dovish than the Fed. But, I can’t say that a single time, in hindsight, my preference would have been better than Fed policy.

The yield curve is actually just moving back up toward where it was last autumn. My gut still says that holding the ultra-short end of the curve artificially high is probably creating more frictions than it is slowing inflation, and that we are playing with fire to keep holding it up above 5%. But can I say that residential investment is being slowed down by it? Not in any way that is slowing down completions, or really even reversing input prices. Of course, industry folks report that starts are being constrained by borrowing costs, and I don’t doubt that there are many projects for which that is the case. There are also commercial properties running into cash flow problems.

But, completion times are still elevated. Homebuilders would start thousands more units every month if they could complete the ones that are under construction. There has been a recent, somewhat sharp decline in lumber prices, but it isn’t really anything out of the ordinary. And multi-family starts have ticked lower. Subscribers have read my reaction to that. Certainly, if those trends continue, it would suggest some moderation on the short-term interest rate target. But, at this point, I wouldn’t be particularly surprised if we end up having strong growth moving forward and the yield curve ends up basically meeting JPow! close to where he’s at.

All that being said, one thing I think we can be certain about is that orthodox macroeconomics, as it is presented to the public, is a mess. The way monetary policy is communicated is “The Fed tightened by raising rates. The Fed loosened by lowering rates.” It is sort of true in the most technical sense. But, more often than not, especially at important moments, the Fed is chasing a volatile neutral rate in one direction or another.

In the recent period, month-over-month inflation (excluding the problematic, lagged shelter component), went from well over 10%, permanently back to roughly 2% in July 2022. The median macroeconomist appears to believe that the Fed was responsible for doing that by raising the target interest rate to 1.5% (with expected future increase of no more than an additional percentage point or 2). But, now, with a target rate of 5.25%, the target may not be high enough to keep inflation in check.

I feel like I’m taking crazy pills. So many people, including economists, seem unfazed by the incongruity of this pair of beliefs. In fact, neither is true. Inflation didn’t recede because of rate hikes, and inflation now is well within the bounds of what normal, 2%-ish, anchored trends look like. But if they were both true, that fact itself would disqualify interest rate targeting as an effective communication framework for monetary policy.

I think, if the Fed followed an NGDP growth target, the 5% NGDP growth target path is still reasonable because growth below 5% was associated with extremely low residential investment. Residential investment is finally poised to return to a level of real activity that might reverse the decline in real housing expenditures. I am not giving up on 3% real GDP growth and 5% NGDP growth until we, at least, try to house ourselves like the developed, wealthy country that we are.

The housing depression hurt GDP growth in 2 ways. First, directly, the deep drop in real residential investment was associated with long-term unemployment, unused capacity, and a whole host of related frictions that lowered domestic production.

But, the lack of housing that results from that increases nominal GDP and decreases real GDP. Think about an economy churning along at 3% real + 2% inflation. Housing should follow a similar track. It did, through the 1970s. In Figure 5, real housing (red dotted line) was flat or rising relative to real incomes through the 1970s. Rent inflation (blue dotted line) was flat or declining relative to other prices.

Then it reversed. Housing demand, on average, is inelastic. So, when we entered full housing depression after 2008, real housing expenditures increased at something more like 1%-2% real annually. And, since demand is inelastic, our total spending on it rises when supply is constrained. So, rent inflation was more like 4%. That’s a 5%-6% increase in spending - because we had less.

But, the 4% inflation is all in land rents. It’s not like more investment is attracted to create more land. It’s an endowment. It’s supply is fixed, and the income flowing to it is just economic rents. Just a transfer from the consumer with needs to the owner with protected privilege.

More on housing, residential investment, and GDP trends below.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Erdmann Housing Tracker to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.