Cyclical Home Prices: Individual Metros

In the previous post, I walked through the various distinct phases of the American housing market over the past 20 years. Some of the observations I make are a little more clear when you look more closely, differentiating city from city. And, so, I will do that here.

As with the last post, the figures that follow will all show the trends in price/income ratios among ZIP codes with different incomes. The ZIP code with average income in each metro area will be at the dark middle line, and the “intercept” vertical gridline near the right hand side of the figures is the ZIP code in each metro area which corresponds with the intercept value in the estimate of price trends that are neutral across the metro area versus price trends that are income-sensitive.

Figure 1 shows 6 metro areas for the period from January 2002 to December 2003. These were the early years of the period when various pundits and economists were increasingly calling the housing market a “bubble”. As you can see, this period was characterized by 2 trends. (1) There was little income-sensitivity in price trends. If low-end homes in your city were up by 20%, high-end homes were probably up by that much too. (2) There were significant differences between cities. Here, LA, Washington, and Miami saw rising prices while Austin, Phoenix, and Detroit were pretty stable.

Figure 2 shows December 2003 to June 2006. These are the early years of the subprime boom. Austin and Detroit remained moderate. Phoenix joined LA, Washington, and Miami in having high rates of price appreciation. Note, though that Phoenix doesn’t particularly look like those cities, because in Phoenix, homes across the city appreciated by about 40%, but in the other cities where prices had been appreciating for longer, price appreciation had become more income-sensitive.

Is there a correlation between the “boom” or “bubble” cities and subprime lending? Maybe? Not really? I think you can get to an explanation much more clearly with other factors. Supply and demand gets you there much more clearly, I think. Some cities had more demand than supply, either because of a spike in the former (Phoenix) or a lack of the latter (LA). And, the quintessential subprime bubble city out of these 6 - Phoenix - is an anomaly in having a boom as strong in high-income ZIP codes than in low-income ZIP codes.

These patterns are driven by migration. Spikes in in-migration (like Phoenix then or Austin today) tend to drive up prices in general. Price trends that become income-sensitive are more likely due to internal migration, where there is a bidding war for existing homes, that systematically must lead to a segregation so that poorer residents migrate away. Some demand from inmigration can be a part of that process, but it is more of a long-grind.

Prolific research partners Mian and Sufi and authors of “House of Debt” argue that debt was flowing just as much in Detroit as in Los Angeles, and this proves the causal importance of debt expansion. It only led to price spikes in supply constrained LA. But, if there had not been a debt boom in Detroit, that would have been evidence that supply constraints led to rising prices and more debt only where supply was constrained. The fact that debt was also flowing in detroit says that the lack of supply in LA wasn’t the primary cause of rising debt. Rising debt caused rising prices where supply was constrained. It’s a valid argument which calls for its own post.

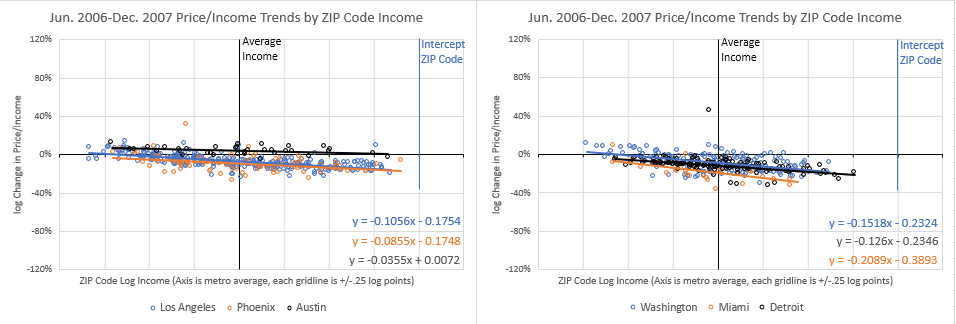

Back to the price trends. Figure 3 covers June 2006 to December 2007, which includes the later subprime boom, the synthetic CDO boom, (The Big Short was set during this time.), and the initial collapse of those lending markets. The mortgage cohorts with extremely high default rates were originated during this period. One thing to note is that those bad loans weren’t really part of a bubble. They were originated during a pretty deep contraction in housing. Maybe subprime lending at the low end was helping to prop up that part of the market during this time. I think that’s an open question.

But, I think it has been underappreciated how deep of a top-end housing contraction there was before the bottom of the market collapsed. The conventional story is that mortgage defaults on poorly underwritten loans triggered a wave of pro-cyclical inventory. Defaults really were just starting to rise to unusually high levels toward the end of this period. Before that became a big issue, home values in the richest neighborhoods of all of these metros (except for Austin, which remained stable) had collapsed well into double digit losses, relative to incomes.

I have mentioned the pivotal August 2007 Jackson Hole meeting for the Fed in a previous post, and I go into it in my latest book. I have generally discussed it in terms of supply. Ed Leamer famously (and correctly) argued that housing starts are a key leading indicator that the Fed should watch, and even target, and that by August 2007 starts were signaling recession. And, then he argued that this time was different and that the Fed couldn’t aim for a recovery (because he was wrong about supply conditions). He also (correctly) argued that housing was important in the business cycle because it represented volatile production activity, not volatile price activity. And, that was more or less right, if you just looked at average price trends, when he spoke to Fed officials. But, really, even by the end of 2007, as you can see in Figure 3, the top end of most cities was already well into a deep price collapse. As the last post outlined on a national level, in ZIP codes with high incomes, the boom had basically reversed by the end of 2007. That was largely benign as a macroeconomic issue because the richest neighborhoods aren’t very susceptible to default spirals.

One other thing to note about this period is that, contra-Tolstoy, while cities were all happy in their own ways before 2006, after mid-2006, they were mostly unhappily alike. National macro-management had taken over. After my years of research and consideration on this, the many complaints about bail-outs, “Greenspan puts”, concerns that the markets needed disciplined, etc. over the course of 2008, are really statements whose subtext was that a cycle reversal that was benign wasn’t good enough, and that the complainers demanded macro-economic policies that would create a default spiral. The tragedy of 2008 was that, since nothing of the sort was necessary, a lot of damage had to be inflicted on the American economy in order to give them what they wanted.

What the Fed started, the mortgage regulators finished. By the end of 2007, the federal mortgage agencies were the primary source of mortgages remaining, and they greatly tightened lending standards, and that change shows up in spades in the price trends in Figure 4.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Erdmann Housing Tracker to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.