Former head of Countrywide Financial, Angelo Mozilo, has passed away. As the Fortune headline notes, he “became the face of the 2008 housing crisis” because Countrywide was a leader in subprime mortgage lending.

Lance Lambert shared (via a Nick Timiraos tweet) an August 2005 e-mail from Mozilo expressing concern about an overheated market and loose underwriting. Here is an excerpt:

Troy is in the Detroit area. In “House of Debt” Mian and Sufi also cite Detroit as one of the areas of interest in the housing boom and bust. I hope to eventually do a more detailed dive into Mian and Sufi, but with Mozilo’s passing and this e-mail, a walk through the housing boom and bust in Detroit might serve as an introduction to my alternative approach to the conventional histories of the time.

My complaint is that the narrative of a housing market driven by recklessness and debt was established in real time. It wasn’t really an empirical conclusion. It was a presumption. A thousand academic articles and books were written to investigate the role of loose lending, speculation, loose money, government subsidies, etc. in the housing boom and bust whiles zero articles were written about the role of inadequate supply. And, lo and behold, those investigations concluded that some combination of those demand side issues was to blame, though we can’t seem to come to agreement about which ones. So, a time associated with a spike of outmigration of millions of poor families away from cities with high rents, in search of second-best alternative cities that they could afford, has gone down in history as a tragedy created by reckless financiers.

The normal narrative is that reckless lending to unqualified borrowers drove up home prices to unsustainably high levels, which triggered a bunch of unsustainable homebuilding activity. Loose money and loose lending kept the party going far longer than it should have. Eventually the unqualified borrowers inevitably couldn’t keep making the payments on their reckless mortgages, and when they started defaulting, the bottom finally fell out. At that point there was little to do but to take our medicine and to let the rot work its way out of the system.

I suppose Detroit is a point of focus because we can imagine it being populated by a lot of unqualified borrowers. The problem with citing Detroit as a location where this narrative unfolded is that there were neither extremely high prices nor a large amount of new building there. Eventually, if you keep removing vegetables from your soup, it can’t be vegetable soup any more.

Mozilo’s concerns weren’t coming from nowhere. Yet even on the point of anecdotal accounts of reckless lending, which surely were numerous before 2008, at most this could accumulate to a few percentage points of the housing stock over the course of a few years of a lending boom.

As I outlined in “Shut Out”, even the story about a surge of unqualified borrowers is hard to confirm with aggregate data about homebuyers and homeowners. According to historical Census Bureau data, the homeownership rate in Detroit was 76.1% in 2001 and it was still 76.1% in 2007.

If home prices were moderate in Detroit and housing construction was flat, what exactly is the trigger to turn Detroit’s housing market into a once-in-a-century bust? The defaults of a few borrowers out of every hundred homes should knock 50% of the average price of homes across the entire metro area?

It beggars belief. Or it would if the story hadn’t been so universally presumed to be true that every ounce of collective confirmation bias came to its defense.

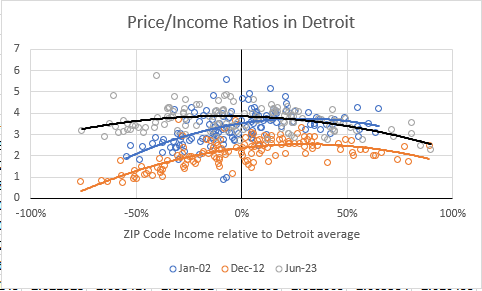

To walk through what happened, I will use my standard form of chart. These are scatterplots of the price/income ratio in each ZIP code, arranged by ZIP code income. In order to create an apples-to-apples comparison as incomes change over time, I will show the change in price/income ratios with the ZIP codes arranged so that the average ZIP code income in Detroit is at the origin in any given year.

Detroit is a very affordable city. In fact, it has a strange pattern common only among some rust belt cities. The price/income level in the poorest ZIP codes is lower than it is in the richest ZIP codes. This is likely due to regressive property taxes, depreciated and under-maintained homes in neighborhoods with high vacancies, and negative amenities in declining parts of town. But, for our purposes here of reviewing the housing boom and bust, the important point is that the purchase price of homes in Detroit is not the constraint on homeownership. That’s why the homeownership rate is relatively high.

As Figure 1 shows, that was true in 2002 and it was still true in August 2005 when Mozilo expressed his concern.

This doesn’t mean that there wasn’t some reckless lending going on, or even lending with predatory terms. But it does mean that whatever lending was happening, it wasn’t creating an unaffordable housing market with prices that would have to drop aggressively to be normal again.

By the way, in Reassessing the Role of Supply and Demand on Housing Bubble Prices, I estimated the scale of supply constraints, local factors like migration, credit access, and speculation on home prices from 2002 to 2006. I found a large effect for credit access in Detroit! (Figure 2) As much as a 20% increase in prices in some of the more credit-constrained ZIP codes. This is larger than the effect typically found in the housing bubble literature!

What I found in that paper was that credit access was associated with buying activity in locations where other factors were decreasing relative home prices. It wasn’t associated with housing bubbles. It was associated with moderating prices in places where homes remained affordable.

Figure 3 shows the change in price/income levels in Detroit ZIP codes from January 2002 to the month of Mozilo’s e-mail in 2005. An increase of about 0.3 points where price/income levels are around 2 or 3 is about a 10% price appreciation. If credit access was associated with a price increase of 20% over this time, then that means that prices might have declined by 10% without it.

Now, of course, there could have still been a surge of predatory lending. Or, you can construct any number of narratives of different buyers in different ZIP codes doing whatever you want. Maybe mortgage lenders suddenly lurched from selling mortgages to the marginal 24th percentile family (because the top 76% were already homeowners) to selling mortgages to the 5th or 10th percentile families who had no business being owners. There are countless predatory lending stories you can put together, and many of them contain some truth. But, again, they can’t add up to more than a couple percentage points of homeowners and they clearly didn’t move prices much.

Furthermore, in Figure 3, I have included the change in home prices from August 2005 to December 2007. Subprime lending in the privately securitized markets had basically dried up by the middle of 2007. Notice what happened to home prices. (This is common across the country.) During this period, prices at the low end held firm while high end price/income ratios dropped by more than half a point.

The convention is to blame declining prices on the collapse of unsustainable lending. Defaults were slowly starting to rise in 2006 and 2007. Isn’t it strange that the initial drop in prices was in the richest, least credit-constrained neighborhoods? Are those the neighborhoods Mozilo was worried about lending to?

Figure 4 is also from my paper. From 2006 to 2010, I show a reversal from credit access similar to the gains from the earlier boom period - as much as 20% in some ZIP codes. But, the main problem in Detroit was a 40% decline in homes across the city from general local effects. This was not due to reckless lenders.

Also, notice that the residuals (changes in prices that aren’t associated with variables in my model) are correlated with income. Even after accounting for credit access (which I estimated with FHA market share and denial rates on new mortgage applications), ZIP codes with low incomes saw deeper drops in home prices. This was common across cities. The typical slope of that correlation between unexplained price changes and income after 2006 is one of the factors I used to estimate my credit variable.

After the end of 2007, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac started sharply tightening credit access even among prime borrowers, which I estimate here monthly with the credit component of the Erdmann Housing Tracker. My contention is that the correlation between the residuals and income in Figure 4 for the 2006 to 2010 period reflects the effects of novel tightening in credit access that reached well into prime borrowers, and remains in place today.

Figure 5 shows the initial effects of the new tightening. In 2008, up until the climax of the crisis in September, prices in poorer neighborhoods started to decline faster than in richer neighborhoods. Cumulatively, however, even by September 2008, high end homes had still lost more than low end homes. This is nearly a year into the new tightening of credit at Fannie and Freddie, a year since subprime lending had completely dried up, and more than 3 years after housing construction had started steeply declining in Detroit from the moderate pre-boom levels. We were well into a deep housing contraction before low end home prices started dropping faster than high end prices. They did not lead us into the contraction by any stretch.

At the end of 2008, the Fed stopped the steep economic decline, but the harsh new lending standards at Fannie & Freddie remained in place. The high end of the market now stabilized, but it was during this period that the real damage was done at the low end. As Figure 6 shows, the bulk of the collapse of low end home prices in Detroit was very late in the process. Price/income ratios fell below 2 in much of the city. Dare I suggest that a lot a families in Detroit in 2012 could have used the services of Angelo Mozilo to get in on those smoking deals?

Isn’t it weird to blame a bunch of reckless mortgages that Mozilo was worried about in 2005, which weren’t originated in any quantity after mid 2007 for a housing price bust that mostly happened years later? But the bankers did this to us. Right? We had decided that by 2004. We hauled them to up Congress countless times during the period when the actual crisis was happening after 2008 so our representatives could scold them in person. You did this to us! This thing that is happening right now, years after you left the business! This is on you!

Of course, as I document here at the tracker, the result of that moral panic has been that low end homes in cities across the country are now more expensive than ever. Figure 7 compares the price/income changes of 2008 to 2012 to the changes from 2012 to today. Now, there’s a chart that screams “subprime lending bubble” if only there was any subprime lending to pin it on!

The final salt in the wound here has been the proof of a null hypothesis of sorts, that tight lending might not be great for keeping home prices down. So now we blame private equity investors or some such for the high home prices in Detroit that loose lending could never have created.

Figure 8 compares price/income levels across Detroit in 2002, 2012, and today.

Rest in peace, Mr. Mozilo. Maybe what you were up to wasn’t all as terrible as it was made out to be. Whatever the pros and cons were of the world you tried to create, it seems that in the end the world without you was worse.

(Sung to the tune of Those Were the Days)

And you knew who you were then

girls were girls and men were men

Mister we could use a man like Angelo Mozilo again

People seemed to be content

fifty dollars paid the rent…

Great post. As someone who lived through it on a trading desk, the true "villian" was the structure of leverage in the system. It built up over years on the back of several variables that were self-reinforcing. It's simpler to blame one person or institution (Angelo! Freddie! Rating Agencies!), but that's just not what happened. It was a complex system. And watching repo markets upend in a very short period of time was nothing but spectacular. I've always thought Gary Gorton did a great job capturing what happened. Just amazing how even in 2023, <1% of the public can explain this.

but he was named Angelo, had a swarthy complexion, and wore a tailored suit, so he had to be the villain, right?