Cool Paper on the progressive effect of upzoning

Here is an amazing paper. The things people are doing with data these days are incredible. Vincent Rollet at MIT used parcel level data to track the effects of targeted rezoning in New York City. He was able to quantify how rezoning leads to infill construction. In a nutshell, developers need to be able to add to what is there in order to make redevelopment economical, so redevelopment happens in the least dense, most valuable locations.

He was able to identify and track 833,000 individual parcels from 2004 to 2022. Only 22,000 parcels were redeveloped over that time.

From the paper:

I find that redevelopment is usually unprofitable in inexpensive or densely developed neighborhoods, severely hindering their ability to change regardless of the stringency of zoning. Zoning regulations primarily distort development in areas with high floorspace prices and low density. In NYC, I show that the targeted upzoning of these neighborhoods can substantially boost floorspace supply. However, the effects of upzoning take time to materialize, and its impact on rents is diffuse. Local upzonings may thus initially appear disappointing to policymakers aiming to improve affordability, but over time and in aggregate, they yield large gains.

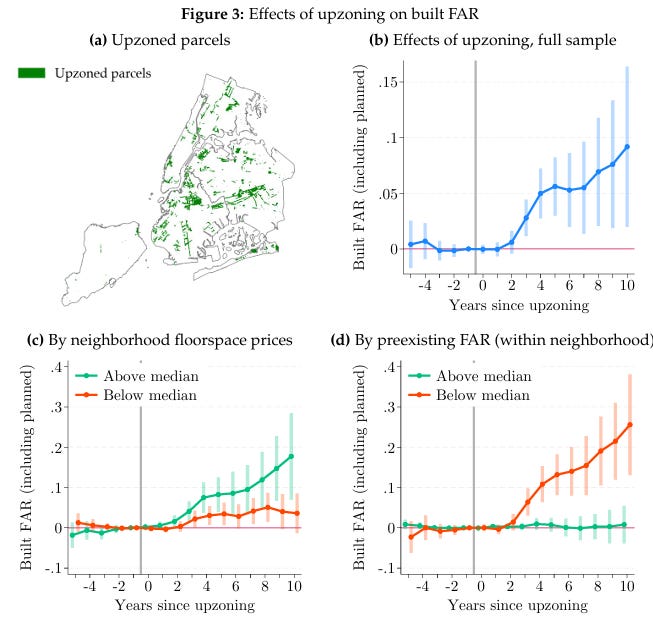

Figure 3 from the paper quantifies the effects he found. Upzoned parcels started the period with a built FAR (floor area ratio - the proportion of floor space allowed on the parcel relative to the size of the parcel) of 1.3. On average, upzoned parcels increased FAR by nearly 0.1 over the following decade. Parcels with above-average value added nearly 0.2 points and parcels with below average density added more than 0.2 points.

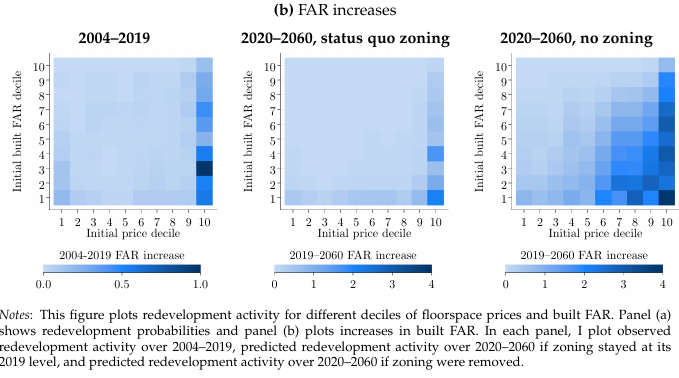

In the next figure, he demonstrates the effect of upzoning across both dimensions - density and value. After upzoning, expect very little redevelopment in dense, low-value parcels, and significant redevelopment in the least dense, high-value parcels.

Keep this pattern in mind in light of the insights of my work. The shortage increases the price of parcels in low-income neighborhoods proportionately more than high-income neighborhoods. Under zoning constraints, then, redevelopment is more likely to be nudged into low-income neighborhoods. Opposing upzoning probably mostly protects low density wealthy neighborhoods and creates more displacement in low-income neighborhoods.

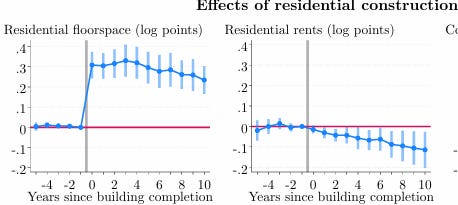

Next, he models the effect of redevelopment on rents within 500 feet of the redeveloped parcel. The results are underwhelming. A .3 log rise (about 30%) in floor space is only associated with a little more than .1 log decrease (about 10%) in rents over 10 years. The demand elasticities I usually find that I use in the Metro Area Analysis packages would associate a 0.3 log increase in housing supply with a 0.6 log decrease in rents.

One reason for the underwhelming result is that the effects of supply are distributed broadly throughout the region. In fact, it wouldn’t have surprised me if he had found no local rent effects or even some positive rent trends in the very local area.

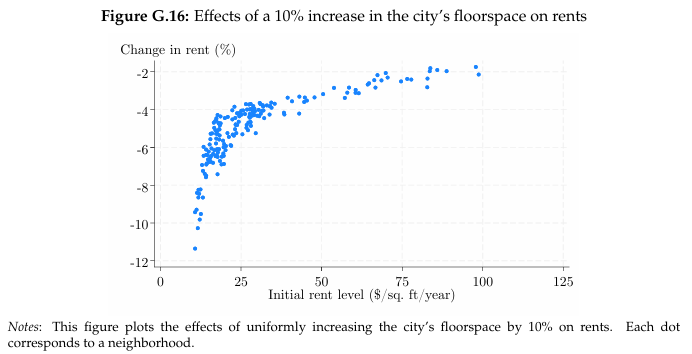

In Figure G.16, he estimates the effect of broad upzoning on rents across the market, and finds that the effects are highly progressive, lowering rents the most in parcels where starting rents are lowest.

This still seems low - a 10% increase in floorspace leading to about a 5% decrease in rents, on average.

In the top-down approach I use in my Metro Area Analysis packages, about 28% of the average rent in New York City is due to the scarcity premium that has accumulated since 2000. And, I put the shortage that led to that premium at about 2 million units, or a bit more than 20% of the housing stock. Rollet’s estimate suggest’s that New York City would have to add significantly more than that to reattain 20th century affordability.

Also, consider these estimates at a national scale. Since 2008, excess rent inflation has accumulated to around 20%. It would take 15 million extra new homes to increase the stock of homes by 10%. Pick your elasticity and scale your estimate of the shortage accordingly.

Rollet estimates construction costs ranging from $185 per square foot for 1-3 story apartments to $1,712 per square foot on skyscrapers with FAR above 20. You could argue that density raises the cost of construction, and that if you factor in those costs, removing the scarcity premium requires increased costs that mediate the effect.

I just don’t think it is plausible that high construction costs could push that hard against the scarcity gains. The scale of the scarcity premium is too large and too recent to not be largely reversible.

I think high construction costs largely end up changing the distribution of the housing stock across households and the size and quality of the housing stock. Scarcity, at the scale New York City is enforcing it, leads to an existing family spending 50% of their income on rent instead of 35%, after living in the same unit for 20 years. High cost of construction leads more to a newcomer living in a 1,200 square foot unit with a 30 minute commute rather than a 1,600 square foot unit with a 10 minute commute.

I am not qualified to reverse engineer the model in the paper, but he notes that, “As time passes, redevelopment increases the total amount of floorspace in the city, which tends to lower residential rents and increase wages. This raises residents’ expected utility and causes the city’s population to grow through migration. I assume that the number of workers of each skill level in the city grows with their expected welfare, with a migration elasticity εM of 3 (this corresponds to a typical estimate in the literature).”

My intuition here is that there are a range of “migration elasticities”: the newcomer who might have inelastic demand in terms of migrating but very elastic demand in terms of what unit they take when they arrive, existing residents in growing cities who have perfectly inelastic demand in terms of units used but nearly unitary elasticity in terms of the unit (If they were spending 20% of their income on rent and rent/income declines to 15%, they might trade up to a unit whose rent takes nearly 20% of their income within the stock of homes.), and existing residents in housing constrained markets who have perfectly inelastic demand in terms of both occupying a single unit and in terms of paying inflated rents on that unit without changing units, until they reach a tipping point and migrate away beyond some untenable rent level.

These combinations of demand behavior surely create non-linear demand slopes depending on whether a city is taking in net migration versus shedding net migration. Just trying to think intuitively about it, I suspect that a market like New York City would have various regimes of migration elasticity. With some marginal additional housing, I would guess that mostly it would reduce the number of outmigrants without lowering rents substantially because their transition from outmigrants to remainers would take place at the highly elastic tipping point. More building beyond that would tend to lower rents for existing residents who have been paying more to remain in the worst viable units they could accept, so rents would decline sharply. Then, as supply increased from there so that housing consumption was increasingly dominated by downward filtering of existing homes rather than upward filtering, increased consumption and in-migration might cause rents to be less sensitive to new supply.

Those are all just intuitions. But, whether all of that is exactly right or not, I suspect that using a constant for migration elasticity could create some situational biases that understate the effect of supply on rents in New York City under broad enough upzoning to create net in-migration.

My contention is that elevated home prices in our housing constrained cities is largely driven by the willingness of existing residents to pay for idiosyncratic endowments. In other words, some families are willing to pay much more to remain in a location where they have deep personal and family connections than they are willing to pay to move to a new opportunity. As far as I can tell, the author uses spatial equilibrium models which focus on amenities and wages that drive aspirational moves and doesn’t account for the ransom rents paid under duress in cities with perpetual displacement.

But, as I wrote above, I am not in a position to fully reverse engineer the statistics, so at most take my comments as food for thought and not as an authoritative review of the author’s work. Comment if you’ve seen the paper and can add color.

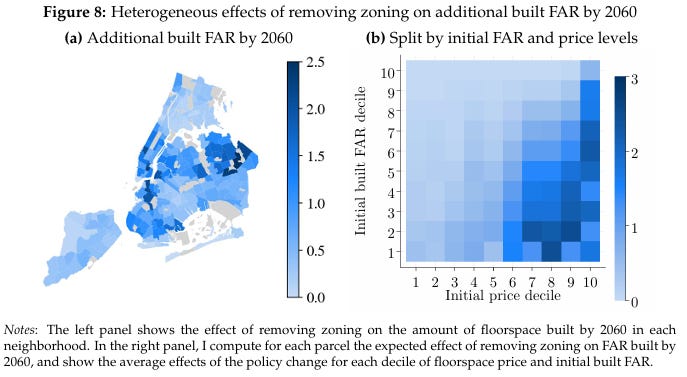

Figure 8 from the paper highlights where increased density would likely occur under broad upzoning. In zoned American cities, city centers have a lot of room to densify, but having frozen our cities in amber for a century, it is the few miles around city centers that have remained at very low densities that would likely develop the most. He estimates that most of the upzoning would be in parts of Brooklyn and Queens plus a couple of the least dense pockets of Manhattan.

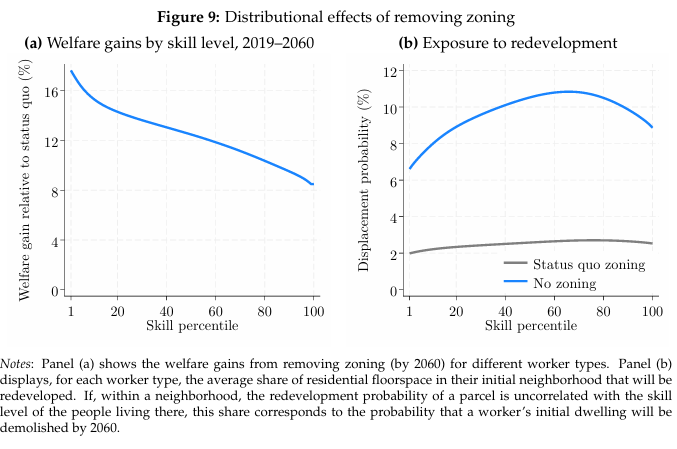

Figure 9 from the paper estimates welfare gains by skill level and the potential for displacement caused by redevelopment. This is over a 40 year period. Again, as far as I can tell, the author treats all migration as aspirational and utilitarian migration from spatial equilibrium models and isn’t accounting for the fact that more than 1% of existing residents with below median incomes are regionally displaced in a typical year under current conditions, and that much of the elevated rent is due to families paying high rents to avoid displacement. With no redevelopment, probably something around half of low-skill-level residents would be regionally displaced by 2060. So, I think the right panel of Figure 9 greatly understates the benefits of upzoning. Given the current rates of regional displacement, I think it is mathematically implausible that redevelopment would increase local displacement more than it would decrease regional displacement. I think his model here assumes all migration triggered by redevelopment or the lack of it is internal, but I might have missed something.

The paper also includes some interesting comments on the history of zoning, and how we got here.

The substantial welfare cost imposed by NYC’s stringent zoning is reflected in the large gap between the price of floorspace and its marginal construction cost. In 2019, building an additional housing unit in NYC cost about $400,000, while the average home sale price approached $1 million. For such construction to reduce welfare, it would need to generate a net negative externality of at least $600,000—an implausibly large effect. If anything, the evidence points in the opposite direction: new development in NYC seems to create positive externalities. Therefore, when zoning prevents the construction of a new housing unit, it typically results in a welfare loss of several hundred thousand dollars. This raises the question of why urban planners impose such costly policies. I argue that the inadequacy of NYC’s zoning code stems from the economic conditions at the time of its initial adoption, combined with the strong persistence of zoning policy, which is more enduring than planners often anticipate.

When NYC’s current zoning resolution was drafted in the late 1950s, population growth had come almost to a halt and land values were below their historical trend. At the time, urban planners believed the city had nearly reached its ultimate size, and their main aim was to guide NYC’s future growth, which they believed would be limited, particularly by promoting tower-in-the-park architecture and further separating commercial development from residential areas. Such separation of land uses was partly justified by the negative externalities of manufacturing, which accounted for approximately 30% of employment in NYC until the 1960s.

In the mid-20th century, floorspace prices in NYC were roughly equal to marginal construction costs. Therefore, small negative externalities could make new construction welfare-decreasing and justify zoning restrictions. Furthermore, as new construction did not yield substantial surplus, limitations on floorspace supply were not particularly socially costly. Hence, when the 1961 resolution was adopted, its potential costs were limited and the existence of a large manufacturing sector made zoning potentially beneficial. Economic conditions in NYC have changed dramatically since the 1960s. With floorspace prices rising well beyond construction costs, the costs of zoning have increased significantly. Furthermore, the potential benefits of the 1961 zoning resolution have likely faded as the externalities associated with commercial land uses have evolved. In fact, contemporary planners typically favor mixed-use developments and oppose tower-in-the-park projects, in striking contrast to their predecessors. Yet, despite these radical shifts, the numerous amendments to NYC’s zoning resolution since 1961 have mainly brought minor changes, and the city’s current zoning map almost perfectly aligns with its 1960s version.

Finally, I have to note one additional thing. Rollet begins the conclusion with:

Cities can expand outward or upward. In the 1990s, 80% of rapidly growing urban areas were doing so mostly outward, by spreading. In the 2010s, this figure had shrunk to 28%, as many cities reached a mature stage. Redevelopment has therefore become an increasingly important phenomenon in urban areas, allowing them to increase their floorspace supply and to reallocate land to its most profitable use.

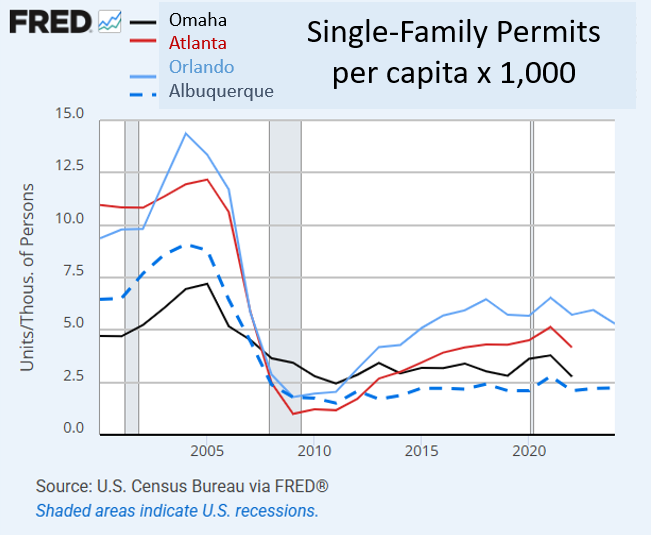

Make no mistake. This paper is important, and cities need to reattain the ability to build up. But, this is just another example of how shockingly uninformed the entire economics academy is about the post-2008 housing market. This paper is thorough, thoughtful, detailed, and has a bibliography that goes for pages, and yet, when noting the shift from 80% of U.S. cities growing outward in the 1990s to 28% in the 2010s, apparently neither Rollet nor anyone mentoring and reviewing the paper knows about the most important event regarding housing markets in our lifetime. “Many cities reached a mature stage.”??????

Omaha, Atlanta, Orlando, and Albuquerque, and almost every other metro area from 100,000 population to 10 million suddenly and coincidentally reached a mature stage in their development? Those commutes in Omaha became untenably long at exactly the same moment that Orlando suddenly became geographically hemmed in by the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean?

With that comment, he cites a paper that looks at global development patterns and finds a shift over time as cities grow. It is certainly a shift that will surely continue to happen slowly over time. But, it’s sort of like agglomeration economies. It is a true thing that has little to do with the specific current trends in American housing markets. And since the entire economics academy is ignorant of the most important thing to happen to US housing this century, they fill in the 80% of the story they haven’t discovered with true and barely relevant causes.

This last Figure is from that paper. Dots to the right represent cities growing outward and dots higher up represent cities growing up with denser infill growth. This is the chart for Houston. The first dot represents growth from the 1990s. Mostly outward. The red arrow points to the second dot which represents growth from the 2000s. Mostly outward. Almost exactly the same growth pattern as the 1990s. The blue arrow points to the third dot which represents growth from the 2010s. A huge collapse in outward growth and a small increase in upward growth.

The paper shows this chart for various global cities, and the average of all of them would very slightly be moving up and to the left each decade. Houston is a bit of an outlier, globally. And Omaha, Atlanta, Orlando, and Albuquerque would all look similar to Houston on that figure. Most American cities would be global outliers on these trends.

Fortunately, this blind spot doesn’t effect the insights of this paper too much. But, yet again, I am flabbergasted at the universality of this blind spot across the academy. We are 20 years into the new normal and the most important fact about those 20 years - that a one-time shock to mortgage access interrupted the construction of some 15 million single-family suburban homes - isn’t in anyone’s peripheral vision. Nobody knew to correct this off-handed comment, which, if you think about the scale of what he’s trying to explain, is not remotely plausible.

(Don’t get me wrong. If we didn’t have the problem of zoning, cities would have been capable of building those 15 million homes upward rather than outward, and that would be preferable for a number of reasons. The mortgage crackdown was important because of the shock it created economically, not because it would have been the optimal form of city-building.)

Think of the work - the millions of hours of work - highly intelligent and sincere academics and policy experts are putting in to try to understand the housing market, and what a mess of confusion so much of that work comes to with that big black hole in the middle of it. Many papers are inside the event horizon. Fortunately, the black hole is not central enough to Rollet’s findings to overwhelm the paper, and, if anything, as I discussed above, accounting for the effects of the housing shortage on household behavior might make the paper more relevant.

I find it encouraging that people besides you are doing good work on this subject. I have a bit of a quibble with the conclusions reached here:

"Cities can expand outward or upward. In the 1990s, 80% of rapidly growing urban areas were doing so mostly outward, by spreading. In the 2010s, this figure had shrunk to 28%, as many cities reached a mature stage."

The "mature stage" he's referring to is actually an artificial constraint on urban development that represents the comprehensive effects of restrictive land use regulations and parts of the building codes. Urban boundary areas, and the suburbs adjacent to them, enacted increasingly punitive zoning codes that effectively stopped outward and upward development from the 1970's onward. The development that occurred during the period from 1970 to the early 2000's was infill that matched the regulatory constraints imposed by these plans and the consequent urban form was large lot suburbs, one story retail and commercial, and pockets of one story industrial/manufacturing. This outcome was regarded as a spectacular success by some planners and much of the voting public. (Full credit to Kenneth Jackson in the Crabgrass Frontier for this description)

Houston remains the outlier in the U.S. that proves that low and medium density redevelopment in the urban ring area can continue more or less indefinitely in a way that responds to demand and holds rents in check. The ultimate example of this urban pattern is probably the Tokyo metro area, which has achieved a scale and architectural diversity that would blow the tiny minds of most American planners.

The United States has manage to kill the redevelopment pattern of "outward and a little bit upward" with its regulatory structures. Consequently, architects and planners remain obsessed with the NYC model of "mega upward" as the antidote to the American suburban sprawl that disperses population and resources outward.

Wonderful write up. So much good analysis, but I particularly appreciate your aside at the end. Since discovering your work, you’ve made a convincing case that the mortgage crackdown kneecapped the single-family market. But I was always confused about whether you actually wanted cities to sprawl vs just preferred building *something* in the absence of infill density. Helpful clarification that you still see building up as better than building out, but in the absence of building up the mortgage crackdown limits the only other outlet for unmet demand. I also much prefer infill, but I’d like to build something!