Anyone with a pulse could get a mortgage

I’m sure basically all of us have heard this. Before the Great Recession, “Anyone with a pulse could get a mortgage.”

Here, I want to walk through some of the basics that go back to my early research. Most of these charts are from “Shut Out”.

Really, even before I began to appreciate the urban housing shortage that was the true center of the American housing story, I was surprised to discover that I couldn’t find evidence for many of the empirical claims at the center of the conventional story.

I mean, I’m not going to deny the basic anecdotes, or even some sorts of odd aggregate activities - reckless or fraudulent borrowing or lending, new untested financial products, etc.

But, given all that stipulated activity, it is just weird how often the aggregate data tell the opposite story. I’m saying, the data doesn’t just fail to reach some sort of statistical significance. It isn’t just weak. It tells the opposite story.

In hindsight, it makes sense that it tells the opposite story. The country collectively “reasoned from a price change” as Scott Sumner would say it. High prices can come from either constrained supply or excessive demand, and if you pick the wrong one, you will consign yourself, not just to inaccurate conclusions, but to conclusions that will be systematically backward.

Combine that with the axiom that housing does, certainly, have cyclical trends, so that demand will go through cycles of rising and falling. If there is a long-term housing supply problem, we will notice that problem only when there are cyclical inclines. And, so, it really is almost inevitable that a housing constrained supply problem will be mis-identified as an excessive demand problem.

Of course, conventional wisdom has been systematically upside-down.

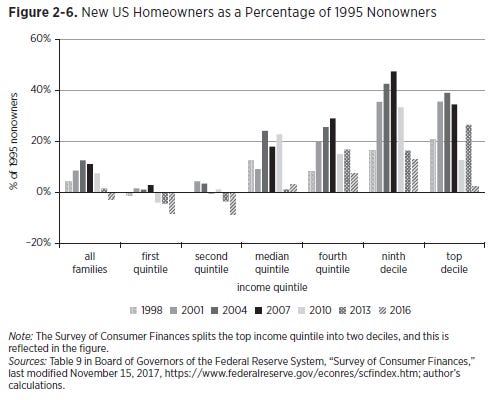

I will walk through a handful of the many charts in “Shut Out”. First, one of the oddities I discovered was that the new homeownership was strikingly focused in the higher income brackets. There was no rise in homeownership in the bottom two income deciles. There was a moderate rise in homeownership in the median income bracket. Homeownership increased significantly among the richest Americans.

One way to look at this, in Figure 2-6, is, “What percentage of non-owners became owners, after 1995?” In total, by 2004, the number of non-owning households had shrunk by about 10%. But that was basically all from above-average households. The size of the non-owning population with top-quintile incomes nearly shrank in half.

There are many sad ironies that come out of the boom and bust. One of them is that, it appears, in the aggregate, that underwriters had actually managed to better match mortgages with qualified buyers. Much of that appears to have happened at Fannie and Freddie by the early 2000s, before bubble mania took hold.

Then we took a billy club to the shins of all those borrowers, convinced ourselves that it was all their fault, and threw all that underwriting progress out the window.

On just about any dimension, the rise in homeownership was concentrated on positive attributes - college education, professional career tracks, etc.

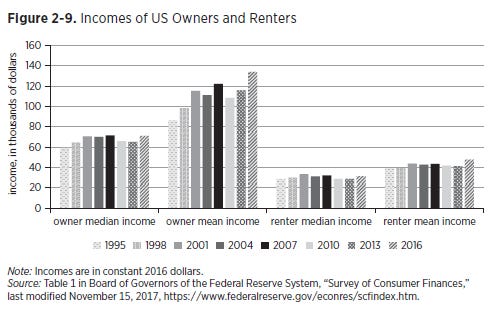

Another way to look at this, in Figure 2-9, is to look at the median and mean incomes of homeowners versus renters over time. Both the mean and median incomes of homeowners increased during the housing boom while incomes of renters remained relatively flat.

Furthermore, the rental values of the homes owners lived in were declining as a proportion of their incomes. Buyers weren’t trading up. When you think about it, if you have been “Erdmann-pilled” as my Twitter faithful say, of course this was happening. The so-called bubble was a mass migration event out of expensive cities to affordable cities. When those families were buyers, many of them were moving to places where their home would have a lower rental value and a lower price because moving was how they could become owners.

Renters were spending a relatively flat amount of their incomes on rent, because at least in the 2000s, building was active enough to start to moderate rent inflation a bit. When incomes and construction collapsed in the crisis, rents took an increasing share of incomes, and that trend has continued since I wrote the book, because construction has never recovered.

Rich families were moving into more affordable homes that they could afford to purchase. Conventional wisdom (which is scattered throughout academia, journalistic accounts, and entertainment media depicting the time) was that unqualified poor families were buying McMansions they never had a chance to afford.

Finally, the Federal Reserve tracks the number of households with debt payments that are considered distressed - taking more than 40% of their income. Again, there was little movement in that trend for families with median or below median incomes. The families that suddenly started taking on more onerous debt payments during the subprime boom were families with the highest incomes.

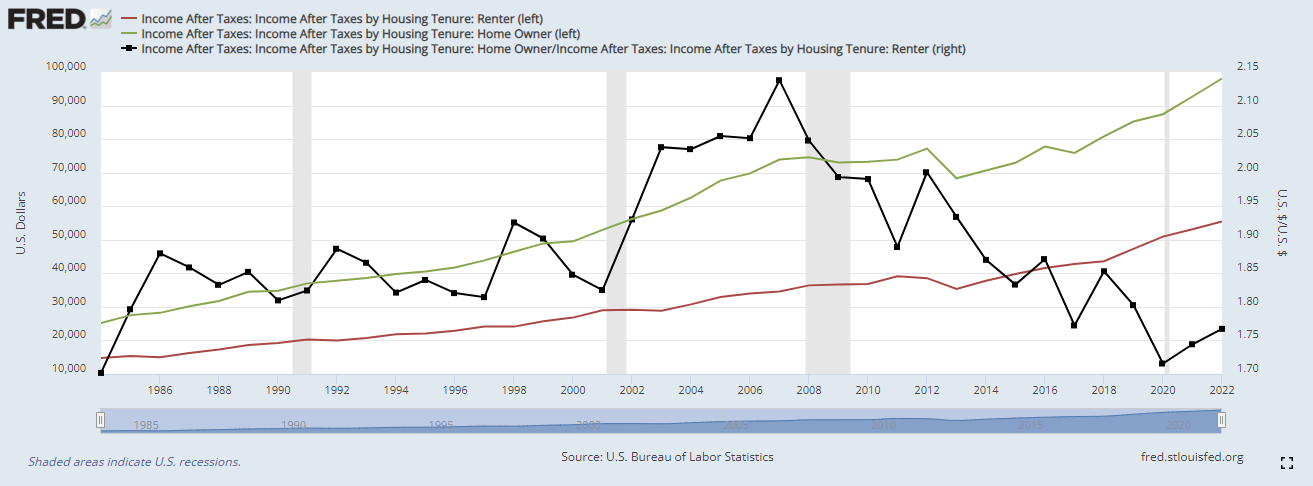

And, either I have never happened upon this data or I have forgotten about it. But, the other day, I was poking around FRED, and found this.

You’ll notice that all the charts above are reported in 3-year increments. That’s because that data comes from the Federal Reserves’ Survey of Consumer Finance, which is reported every three years.

Well, here is a different survey, taken by the BLS annually since the 1980s. And it confirms the SCF. Again, this is in sharp defiance of the conventional wisdom. Between the 2000 recession and the 2008 recession, there was an anomaly in American homeownership - homeowners had unusually high incomes!

Here, the green line is the average homeowner income, the red line is the average renter income, and the black line is the ratio of homeowner/renter average incomes.

In the SCF, owner incomes have tended to continue to outpace renter incomes while in this BLS Consumer Expenditure Survey data, the ratio returned back to pre-2000 levels. I’m not quite sure what the difference is.

In either case, both surveys display a surprising trend, in light of the “anyone with a pulse” conventional wisdom, during the lending and housing boom. One way to square the circle is that increasingly the privately securitized loans that ended up blowing up were going to investors. So, there is a story here that can confirm that lending or borrowing got out of hand, that some of those markets were bound to blow up, and that those markets were mostly unrelated to mortgages for homeownership.

My response to that is, “BUT THEN WE REGULATED AWAY A LOT OF HOMEOWNERSHIP MORTGAGES!!!”

In any case, I understand the difficulty here. This data is surprising. Very surprising. And, so it leaves one with really only two options. (1) Keep following your nose about all the other data related to the housing boom and bust with an open mind, or (2) disengage from this data because it doesn’t comport with the dozen other things that conventional wisdom has assured you are correct.

I suppose it’s a sort of weakness of Bayesian reasoning in practice, because in the practical world, once we become collectively confident enough in a set of beliefs, those beliefs basically get a 100% presumption of certainty. We have to do that to function in the real world.

This leads to an oddity in human understanding. In the physical world, things naturally correct, and the more out of whack they are the faster they correct. The hotter a pot of water is, the quicker it cools. In human understanding, the more wrong someone is, the harder it is to correct, because to become really wrong, a somewhat wrong belief likely had to inherit a presumption of certainty along the way.

Looking back at that first figure, it then is inevitable that the most common reaction to a supply crisis will be nearly impenetrable confidence about a range of apparent sources of excess demand. This makes housing especially challenging. Maybe there was no other likely path except for housing supply to get very bad. As I have taken to saying, the Great Recession happened because crisis was popular. The coming crackdown on corporate housing investments will be very popular. I just hope there is some tipping point where a plurality of Americans can support letting it get better. That is one thing that I am not certain of, I am afraid.