A Review of Boom and Bust & an Invitation to Subscribe

Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Atlanta: Three Different Housing Stories

If you are familiar with my books, you will know this basic story. Before 2008, there were a few cities with a severe lack of housing. The condition got so bad that families started flooding out of those cities at such a rate, other cities started to struggle to build enough homes to accommodate them. Blaming this problem on loose lending, monetary policy, and other demand-side issues, and believing, disastrously, that we had now built too many homes, American policymakers adopted a “shut it all down until we can figure out what’s going on” approach, tightening monetary policy, tightening lending, and slowing down construction. Eventually this wrong-headed approach created a financial crisis, which the public was eager to blame on the same lenders, builders, and speculators that they had originally blamed for high housing costs.

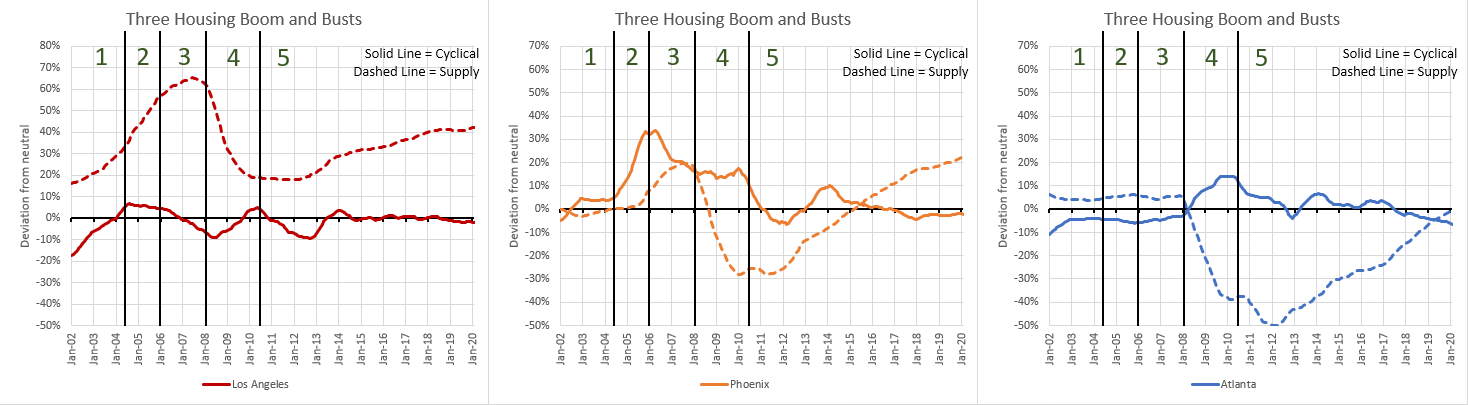

This chart can serve as a guide through those tumultuous times. The seemingly simple output of my housing tracker can differentiate the various experiences of different metropolitan areas through boom and bust. This chart, for the period 2002 to Feb. 2020 and the arrival of Covid, tracks Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Atlanta. The solid lines here track the cyclical component of housing prices and the dashed lines track the supply component

.

Phase 1: 2002-2004

Los Angeles is the outlier in the early boom period. There was some increase in the cyclical component, but mostly, there was an accelerating supply-induced inflation. Los Angeles doesn’t build nearly enough homes, and so they were getting more expensive in the way that inadequate supply leaves its indelible mark. Markets in Phoenix and Atlanta were relatively stable.

Construction activity was high in Phoenix and adequate in Atlanta. There was construction activity in Los Angeles which was at boom levels compared to Los Angeles in the 1990s and at depression levels compared to normal cities.

Phase 2: 2004-2005

Increasingly, the lack of supply was pushing residents away from Los Angeles. Also, increasingly, those movers were cashing out by selling their inflated homes, and they were moving to places like Phoenix looking to reinvest. So, the supply problem continued to increase in Los Angeles and, at first, Phoenix experienced a cyclical boom. Enough money was flowing impatiently into the Phoenix market that a boom was developing, which was likely to eventually reverse. Atlanta markets were still uneventful.

Construction activity continued to be high or adequate, except in Los Angeles where housing frogs had been boiling long enough that depression rates of building felt like a boom to locals.

Phase 3: 2006-2007

By 2006, the Federal Reserve was intentionally and mistakenly aiming at a construction slowdown. Economic headwinds were enough to create some cyclical declines in Los Angeles and Phoenix, but in both cases, since the slowdown involved a sharp decline in residential construction, cyclical declines were countered by a continuation of supply-induced inflation. These countervailing forces were especially noticeable in Phoenix, and they were mirrored by migration trends. As construction slowed, migration out of Los Angeles (which had fueled the cyclical boom in Phoenix) slowed, but migration out of Phoenix to other more affordable places (because now Phoenix itself lacked adequate housing) increased.

The common perception of the Phoenix housing market, that greedy, herding developers built thousands of homes out in the desert where nobody wants to live because they were rabidly chasing a bubble, does not sit well with the facts on the ground. Because of the countervailing forces of declining supply (raising prices) and declining cyclical forces (lowering prices), average home prices in Phoenix were relatively stable until late 2007. By the time prices started to collapse, construction had been declining for a couple of years to less than half the peak. By the time collapse arrived in Phoenix (due to a sudden arrest of long-term population growth trends), overbuilding was simply not a plausible cause.

Phase 4: 2008-2010

This was the period of steepest collapse, and as convention would tell it, there was a cyclical bubble that was reversed by an inevitable reversion to the mean. But, that is only the case with the most cursory view of these 3 cities. The most obvious problem with the conventional story here is that Atlanta had been carrying on as straight as an arrow for years, in both the cyclical and supply components, and then it was suddenly hit with a massive decline in the supply component, (again, as with Phoenix, months after steep declines in construction, from what, in Atlanta, hadn’t even been elevated levels of building). To call the shock in Atlanta multi-sigma would be an understatement.

The reversal in Phoenix wasn’t much less extreme than in Atlanta. There had been a bit of an uptick in supply-related inflation in Phoenix (to reiterate, a sign of underbuilding) and however far the pendulum had swung in boom-Phoenix, it swung much farther in the other direction in bust-Phoenix.

The supply component in Los Angeles is really the only example of a reversal of pre-2008 changes to be seen here. And, to add to the oddity, the declines for all cities were all in the supply components. The cyclical components stabilized or even increased from 2008 to 2010.

The supply component collapsed in every city, regardless of pre-2008 trends because in the two years after the subprime lending boom came to an end, there was an extreme and misguided tightening of credit across the country, well into what would normally be considered prime borrowers. This created a one time average shock to home prices of about 20%, but that shock was highly income dependent. The richest neighborhoods saw little effect and prices in poor neighborhoods collapsed by well over 20%. In other words, our self-imposed credit shock created a signal in home prices that looks very similar to the effect of inadequate supply, except that inadequate supply changes very slowly and the credit shock hit markets like a bolt of lightening.

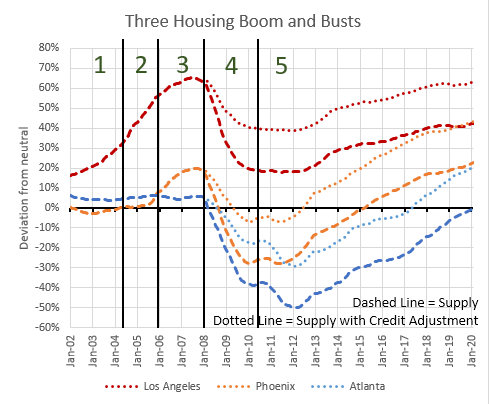

Here is a chart with the Supply component from the first chart (dashed), and the Supply component after adjusting for the credit shock (dotted). (In future posts I will write some more about the credit variable and how I have estimated it.)

Adjusting for the credit shock doesn’t completely reverse the extreme collapse from normalcy in Atlanta, but it gets it a fair amount of the way back. It does reverse the collapse enough in Phoenix back to a pendulum swing that stops at a neutral position. And, in Los Angeles, where there has been a lack of housing all along, and where, as with the other cities, construction had been declining since 2006, the supply line remains high, where we might expect it to be in a supply constrained city.

And, finally, while we made it effectively illegal for working class homeowners to buy homes, driving down prices in their neighborhoods, from 2008 to 2010, we offered those who did qualify for mortgages subsidies - a first-time homebuyer credit - which plausibly explains the rebound in the cyclical component during the same time that credit rationing was tazing home prices in proportion to local incomes (and credit constraints).

Phase 5: 2010-2020

Finally, in Phase 5, all cities settled into a cyclical slumber (until Covid came), but since the poorly aimed treatment for high prices was to reduce them through the blunt force of credit rationing, leading to more than a decade of depression level building in most cities (especially cities with low incomes and a need for reasonable credit access), we have created a predictable ratcheting up in housing inflation related to inadequate supply. We’re all living in LA now. Well, we may not have the sun and the ocean breezes. But we all have rising housing costs which are mainly growing for the families least able to pay them.

All three of these cities were approaching relative valuations of the 2005 “bubble” period as Covid arrived, but that is misleading. Prices, which mainly have been inflated by relentlessly rising rents, would have been 20% higher than “bubble” levels, except that the credit shock continues to be enforced, which discounts the average home by about 20%. Prices relative to incomes are back to where they were in 2005, but in low tier neighborhoods, that is generally paired with much higher rents than in 2005.

Phase 6: Covid period (not shown)

All of this sort of adds up to good news if your main concern is that home prices will decline steeply again. The only way to reverse the supply-effect is through a renewed building boom, which is unlikely to happen if we have a recession. The credit shock was a one-time event. You can’t amputate a leg twice. So our big giant own-goal that was mistaken as an inevitable reversal of a largely non-existent bubble, is now just a big bundle of potential energy that could help fuel the housing boom we would need to bring housing costs back down, and in the meantime, there is little potential to further the damage of 2008-2010.

That leaves the cyclical component. And, there is definitely a cyclical component today - much larger in some cities than in others. My model can clarify where the cyclical component is highest.

So, in a nutshell, there is probably less to worry about than conventional wisdom would make it seem, but there are some things to worry about. And, this is where I have to ask for your support to help make this information available.

Today, I am initiating paid subscriptions at three levels.

Monthly subscribers ($12/month or $100/year) will receive a monthly estimate of national home price trends and sensitivities, which will be posted here on substack.

Subscribers who want access to monthly updates for individual major metropolitan areas can subscribe as founding members. Founding Members ($300/year) will receive the monthly national report and the report on every major national metropolitan area.

I will continue to post analysis for free subscribers, but some analysis, especially that which requires citing up-to-date output from the model, will tend to be for subscribers.

Please subscribe and share!

Below, I have attached the June 2022 spreadsheet of the national average data for paid subscribers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Erdmann Housing Tracker to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.